Luc Forsyth and Gareth Bright have set out on a journey to follow the Mekong river from sea to source. The Diplomat will be sharing some of the stories they’ve found along the way. For more about the project, check out the whole series here.

After seeing Laos’ first ever hydropower dam on the Nam Ngum river, we wanted to investigate the consequences of a more contemporary dam. Over several days we visited the construction sites and spoke to those who had already been displaced by the projects to learn more about the human costs of power.

A passenger vehicle drives along the access road that links the Nam Kong 1 and Nam Kong 2 dam construction sites. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

We had been driving for an hour on the dusty mountain road when we hit the military checkpoint. As the lone passengers in the back of the songthaew (a flatbed truck fitted with benches) we figured it would be impossible to avoid scrutiny and were certain that we would be turned back at any moment. With the media’s widespread — and overwhelmingly negative — coverage of Laos’ Thai-financed Xayaburi dam, we thought that we, as camera-toting foreigners, would be less than welcome at the dam construction sites along the Nam Khan river.

Riding in the back of a songthaew (a flatbed truck fitted with benches) toward the dams. Photo by Gareth Bright

To our surprise, however, the soldiers on duty barely gave us a second glance, and looked more bored than suspicious as they waved us through.

We had come to the Nam Khan to further investigate the human impacts of Laos’ hydropower dams after visiting the nation’s first ever damming project on the Nam Ngum river. The people we’d spoken to there had mixed opinions about the dam’s enormous reservoir (known locally as the Laos Sea) that had flooded much of the area when it was finished in the 1980s. But it had been more than 30 years since the project had been completed and people had had decades to adjust to the change. We wanted to speak to people who were on the front lines of the nation’s current damming rush.

A family sits in front of their allotted home in the Samaky Sai relocation camp. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Voices of the Displaced

A day before our drive into the mountainous valley surrounding the Nam Khan, we had visited one of the main relocation camps for those displaced by the series of dams on the river. Before we saw the dams themselves and spoke to those who were facing eviction from there homes because of them, we wanted to have a clear idea of where these people were being asked to go.

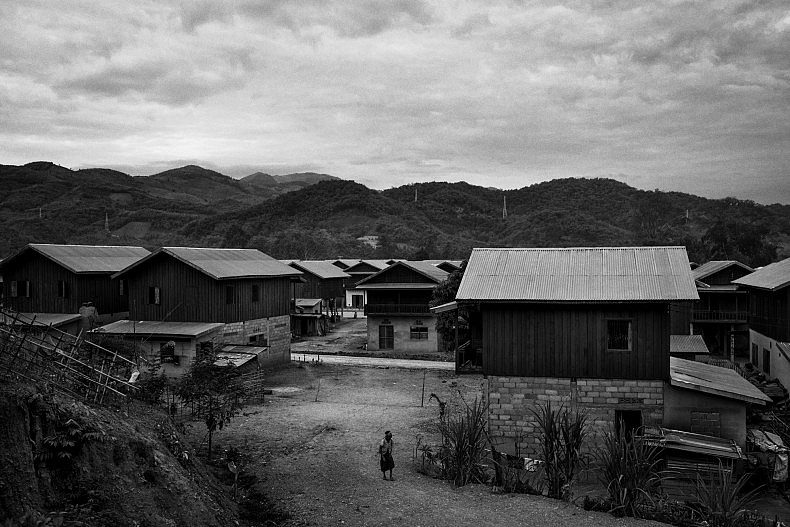

The camp is home to hundreds of families displaced by the construction of hydropower dams. Photo by Gareth Bright.

The Samaky Sai camp, located just outside the village of Pak Hanh, looked artificial in every way. The houses were carbon copies of each other, and clearly built as cheaply as possible; cracks sliced through many of the concrete walls and the roads were uneven and dusty.

Most of the residents used to be farmers or fishermen in remote mountain villages, but since arriving in Samaky Sai have found few employment opportunities other than Sinohydro – the company responsible for their displacement. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

“The old place was better,” a 28-year-old mother of five named Pich told us when we stopped to speak to her on the front steps of the cookie cutter home she had been issued by Sinohydro, the Chinese state-owned firm overseeing the dams construction. “But we didn’t have a choice.”

A billboard about the dam shows what it will look like upon completion. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Pich, like many of the other occupants of Samaky Sai, had come from a small and remote mountain village further up the Nam Khan where her family had farmed rice. While life in the village was far from easy, Pich told us, and lacked access to modern amenities like electricity and plumbing, essential items such as food and firewood had been abundant and cheap. A barter economy allowed her to trade rice for whatever her family couldn’t grow on their own, and a walk into the jungle would usually provide fresh coconuts or bananas. Cash was used rarely, and typically only for specialty items that had to be brought in from the city.

Muoi makes 60 000 kip ($8) per day working as construction worker for Sinohydro. And Pich, 28, is a mother of five who lives in the Samaky Sai relocation camp. Photos by Luc Forsyth.

That all changed when her family moved to Samaky Sai, Pich said: “Over there [in the village] we didn’t need money. But now we need it for everything.” When her family was compelled to leave the village it never occurred to them that they would need cash for nearly everything, and they had no way to earn it. Samaky Sai was too small to provide each family enough space to farm commercially, and virtually nothing would have grown in the hard shale anyways.

Finding the money to buy food has become a constant problem since being forced to leave the village for the camp. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Each person we spoke to throughout the day shared similar stories. Their transition into a cash-based economy meant that their traditional communal farming practices were no longer able to meet their basic needs. They needed jobs. And around Samaky Sai, there was only one real employer.

Chinese construction workers drive through the site of the Nam Kong 2 dam. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

As outsiders the idea seemed perverse, but Muoi was quick to point out that he actually preferred life in Samaky Sai in some ways. “It is more comfortable here because we have a big house and electricity,” he said, but then continued “but it is different. We have to work every day and food is very expensive. Either way I can’t go back because the authorities say that we have to stay here.”

Many of the men living in relocation camps work building the dams that will inundate their villages. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Chanh, a 35-year-old resident of Samaky Sai also employed as a laborer on the dam site, shared Muoi’s preference for the modern conveniences their new home provided, but lamented the loss of free time: “The Chinese never stop working; sometimes we start at 7 am and don’t stop until 7 pm.”

While working a 12-hour shift was by no means uncommon in the world, Chanh explained that the disappearance of their cultural traditions was more damaging than the loss of leisure time. “Every year in the village we used to have a feast to celebrate the new year,” Chanh remembered, “but we had to cancel it last year [after we moved to the camp] because no one could afford the cost of the food. That’s the first time we have ever done this since I was a boy.”

Construction workers on the site of the Nam Kong 2 dam. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

After walking through the camp and talking with Samaky Sai residents for several hours, the stories were essentially all the same. Broom maker Chan Souk, 62, told us how her initial excitement at the prospect of living in a modern house quickly gave way to the realization that their life was forever altered. “When they first showed us the new houses, we all said ‘wow,’ but after a few months we realized there was no food. Here we need money for everything, but in the village we could get whatever we needed from the jungle. It is easier here in some ways because of the electricity, but if we could get power in the village, I would go back.”

Chan Souk, 62, makes traditional Laos brooms in front of her home in the Samaky Sai relocation camp. She says finding the money to buy food has become a constant problem since being forced to leave her village for the camp. Photo by Gareth Bright.

But with the Nam Khan dam nearly completed, Chan Souk knew she would never go back.

Just a few hundred meters behind Samaky Sai was the village of Don Mo, and before leaving the relocation site we wandered over to ask villagers how they felt about the camp. In contrast to Samaky Sai, Don Mo was not a planned camp but a village that had grown organically over generations. There we met 60-year-old pig farmer Phanh Boun Na Phon, and asked if he would be willing to leave his 50-odd piglets for one of the newer houses. He answered with a laugh, but also with decisiveness: “The space there is not enough. The houses are so close together I wouldn’t even have space to park my bike, never mind my pigs,” he said. “I don’t want to live like those people. I have everything I need here.”

A pig farmer tends to his livestock in the village of Don Mo. While just a few hundred meters away from the Samaky Sai (United Village) relocation camp, Don Mo has abundant farmland and the quality of life is vastly superior to that in the camp. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Only the Goats Remain

Back in the mountains, our songthaew bounced along the mountain road as we passed the build sites for the Nam Kham 1 and 2 dams. The scale of the projects was immense, and it was hard not be impressed by the feat of engineering such massive structures in so remote a location despite knowing the human costs involved.

The 3 proposed dams on the Nam Kong river are a massive undertaking. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Workers scurried along scaffolding, looking more like insects than people from so far away, and concussions thudded into our chests as pieces of the mountains were blown away with explosives. Trucks full of workers, presumably being shuttled between their base camp and the construction zones for a shift change, passed us periodically and waved enthusiastically as they called out in greeting. Visitors were not common, we supposed.

The 3 dams are an impressive engineering feat. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

After nearly two hours, we arrived at the third and final dam on the Nam Khan river. Still unsure of whether or not we were allowed to be in the area, we jumped out of the truck and made our way towards the top of the structure. A lone security post overlooked the area, and the guard watched us carefully as we approached. With each step closer to the top, we were sure he would start shouting for us to leave, but as soon as we set foot on the expanse of concrete stretching across the valley he stepped out of his hut and yelled “Hello!” in cheerful if heavily accented English.

A Chinese security guard watches over the top of the Nam Kong 2 dam, which is still under construction. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Not wanting to overstay our welcome, we only loitered for a few minutes to take in the sheer scope of the project before heading back towards Pak Hanh. On the way we stopped at the tiny village of Khone Wai after catching a glimpse of movement in what looked to be an otherwise abandoned community.

Perched on a small mountain side shelf, Khone Wai was situated between dams 2 and 3 on the Nam Khan — placing it squarely in the path of the future reservoir. The majority of houses were empty and looked long-since abandoned, apart from a few that still had laundry hanging from the front porches. At first we seemed alone apart from a few small herds of goats, but eventually a middle-aged man appeared to greet us.

Once completed, the dams will hold back a large reservoir, fundamentally changing the landscape of this part of Laos . Photo by Gareth Bright.

“Everyone is gone,” he told us, “they have all been moved for when the dam is finished [in a few months]. Only the animals are left, and we come to look after them.” Fifty years old and weathered from decades of farming, he politely declined to tell us his name but explained that he would soon be selling the goats and moving permanently to Samaky Sai.

“Yes we are sad to leave, but we have no choice,” he said. “But I am excited to have a new house.”

Once completed, the 3 proposed dams on the Nam Kong river will inundate around 1500 sq km of land, displacing thousands. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

This piece originally appeared at A River’s Tail.