This is the first in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Make sure to read part two and part three.

***

“The personal story of my family is at the same time the story of suffering of all Korean people… I want to tell this story to the world, so that nothing like that ever happens again in our future.”

— Nikolay Ten

***

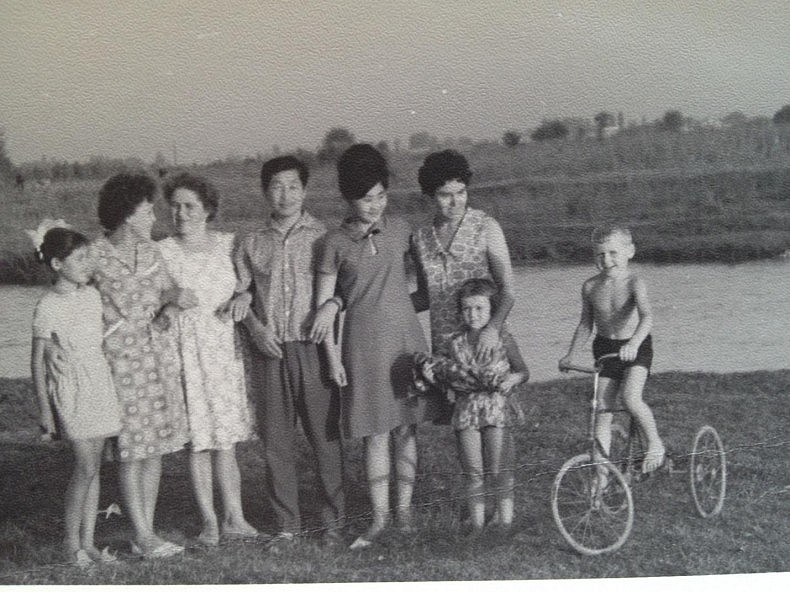

My mom, a half-Korean child among multi-ethnic kids from all over Soviet Union in a Tashkent kindergarten in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Introduction

Strolling along the streets of Tashkent or riding in a small marshrutka minibus – a common mode of transportation in this busy and bustling Central Asian city with a population of about 3 million people – you would feel no surprise looking at the multitude of different faces.

Tanned and dark haired or white skinned and blond, with blue, green, or brown eyes, Russians, Tatars, or Koreans would always appear in the crowd of local Uzbeks. There used to be even more of them here several decades ago, living together in this calm and friendly city full of sunshine and welcoming shade.

A true friendship of people in Tashkent in the late 1960s: Russians, Tartars. and Koreans together, having a rest near the Karasu river. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

By now, many people have left together with their untold stories about this capital of “sun and bread,” a Soviet-day Babylon that became a true Noah’s ark hosting and hiding the survivors of a horrifying storm of ethnic repressions.

Here, lost deep in the heart of a Central Asian desert, they multiplied, prospered and lived in peace. Russians, Jews, Germans, Armenians, Meskhetian Turks, Chechens, Crimean Tatars, and Greeks — most of them had found a second home here, temporary if not permanent.

Some left earlier, as soon as the restrictions on their movement were lifted in the wave of so called “democratization” early in the 1970s.

These people are Uzbek Koreans, and this story is about them.

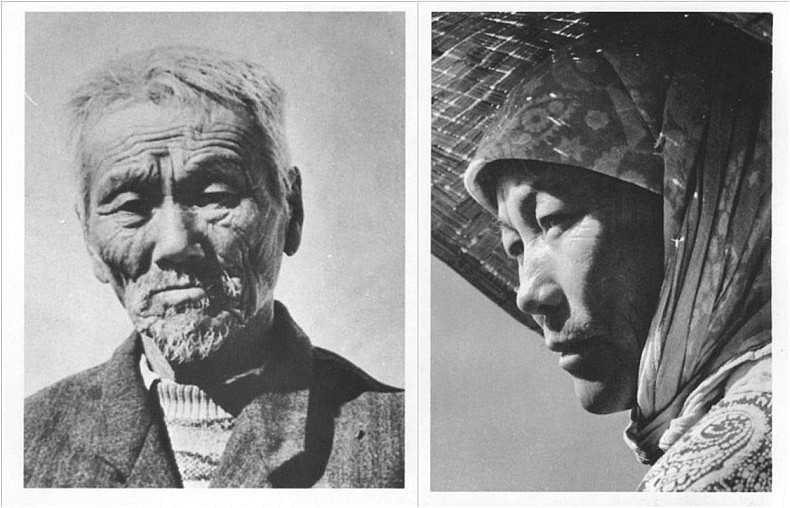

Left: Park Ken Dyo, the creator of kendyo type of rice that rose him to prominence in Soviet Uzbekistan.

Right: A Korean farmer in Soviet Uzbekistan. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

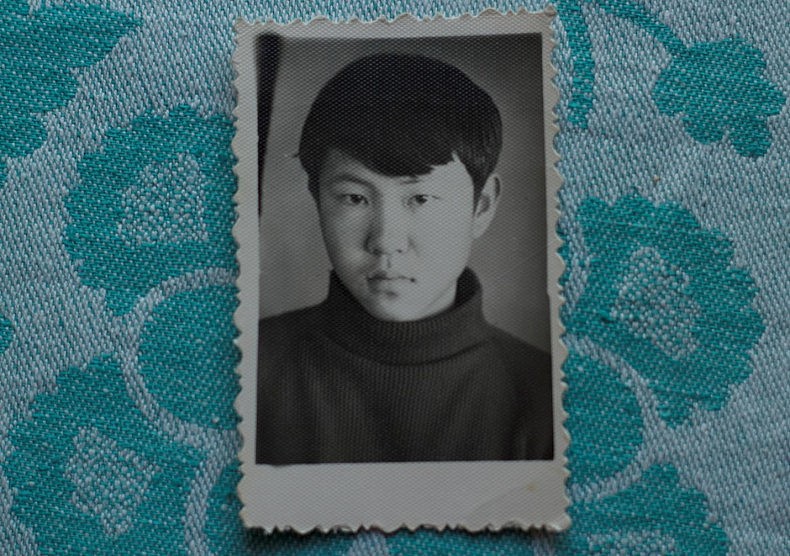

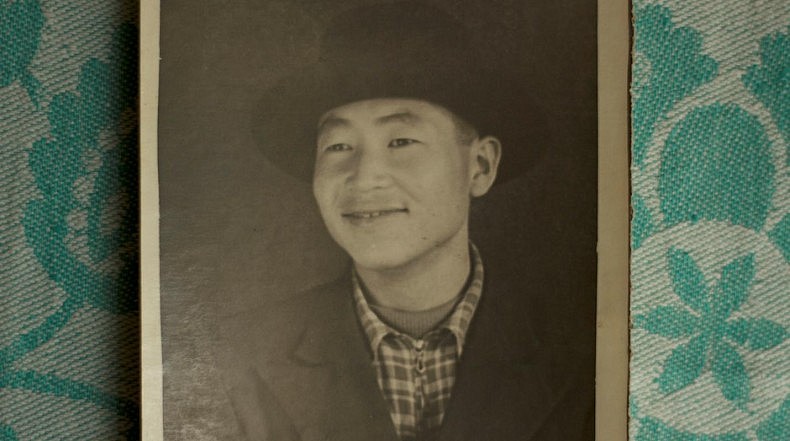

Young Nikolay Ten. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

Nikolay Ten

Nikolay and I were simply bound to meet. When I first saw him on the calm and quiet streets of Tashkent in the early spring of 2014, he was selling souvenirs, antiques, and traditional Uzbek clay figurines to passersby and tourists in the central city square formerly known as Broadway.

Passersby and tourists looking for traditional Uzbek souvenirs on Broadway in Tashkent. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The several theaters it used to host were long gone, as were the crowds. The name has somehow stuck, adding nostalgia and curious mystery to this huge and otherwise deserted area full of flowerbeds and monuments to fallen heroes.

Only a handful of artists, painters and antiquity collectors remained here, including Nikolay, a small and aging Korean man who would pass anywhere for a “typical” Central Asian. He looked more like a Kyrgyz, Kazakh, or Mongol, with his bald head and dark skin tanned by the sun.

Nikolay on the day I met him on Broadway in Tashkent in the early spring 2014. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Something very special on his smooth and round face was his smile – the kind, honest, and hesitant smile of a thoughtful child that he still kept somewhere deep in his heart.

I bounced into Nikolay in the middle of my own personal quest. I was looking for a story almost disappeared and now hidden somewhere near. The ghosts of our recent past were haunting me from all sides on that warm and cloudy spring day on Broadway, and probably, they brought me to Nikolay and made him reveal his story to me.

Uzbek Koreans in the late 1940s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

At the same time, the urge to keep telling this story is somehow very understandable for both of us. These are our collective memories, imprinted in the genes of all Uzbek Koreans.

They are still kept in the taste of pigodi, chartagi, khe, or kuksi – a handful of salty and spicy North Korean dishes that have become a representative part of our vibrant and mixed Uzbek cuisine.

Local Korean sellers at a typical Korean salad stand in Tashkent. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

They still resonate in the sound of a few remaining words in the Hamgyong dialect, which Soviet Koreans originally spoke when they first arrived to Uzbekistan in 1937. They still mark our ancient lunar calendar during the traditional holidays, such as Hansik and Chusok – spring and autumn equinoxes – or tol and hwangab, the auspicious first and sixtieth birthday celebrations.

These ancient and typically Korean festivities and cultural rituals have somehow survived all former official prohibitions and are vigorously observed across Uzbekistan by one unique ethnic group.

The sufferings those stories unveil are always very deep. Equally deep is the pain the memories still provoke.

My then-young grandfather Kim Da Gir. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

My Grandfather

I also have a story woven into the secrets of this tragic past. A long time ago, my grandfather told it to me only once and never wanted to speak about it again.

This is the story of a little boy who traveled one cold winter with many other people, all stuck together inside a dark and stinking cattle train. He traveled on that train together with his parents and siblings for many weeks, until one day they arrived to a strange place in the middle of nowhere.

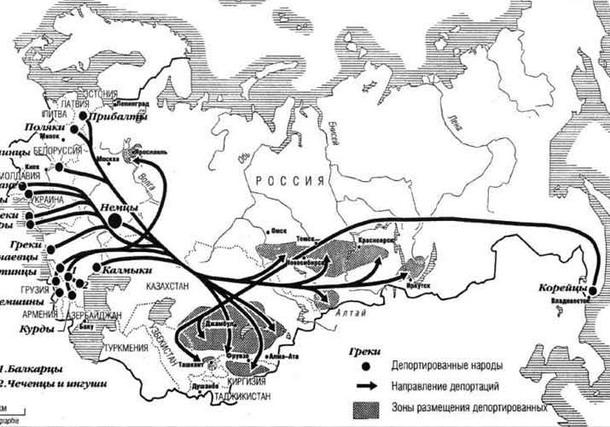

A map showing the forced relocation of “unwanted” ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union throughout the late 1930s – early 1940s. Koreans were the first entire nationality to get deported in 1937 from the Soviet Far East to Central Asia. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

That place was somewhere in Soviet Uzbekistan. It was 1937, and my grandfather was only seven years old.

What brought him to empty and deserted Central Asia was the first Soviet deportation of an entire nationality. What united all of them as the victims of this massive deportation was their ethnicity. They all happened to be Koreans.

In order to affirm my partly Korean belonging I eventually studied Korean, or rather its classical Seoul dialect, which my grandfather was never be able to understand.

Studying Korean together with my Korean classmates in Tashkent in the early 2000s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

I would keep looking for any affinity with Korea and even graduated in the Korean studies at a renowned university in the United States, which my grandfather happily lived to know.

So far from my actual Korean roots and never at peace with this understanding, I would keep looking for those unique Korean stories forgotten and lost deep in Central Asian sands. It would become my personal quest to uncover the secret spaces left blank on purpose, in our family history and in the history of all Uzbek Koreans.

Uzbek Korean heroes of socialist labor in the late 1940s – early 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

My grandfather lived a relatively successful life in Uzbekistan. He went to study in Moscow and was later sent to work in rural Ukraine, where he met his future Russian wife, a woman who was working in the same town. They returned to Tashkent together in 1957, already married and with my one-year-old mother.

For most of his life, my grandfather worked as a chief engineer in the construction bureau at a major industrial plant in Tashkent. He developed and patented a lot of technical innovations for cotton picking machinery – we still keep all his certificates of achievement at home.

Uzbek Koreans are also known for their indisputable role in the development of Uzbekistan’s national agriculture. Traditional peasants, they passed to Uzbek locals their generations-worth of farming knowledge and techniques. Even now, the best types of rice grown in Uzbekistan and used in the preparation of most representative Uzbek dishes are still lovingly called “Korean.”

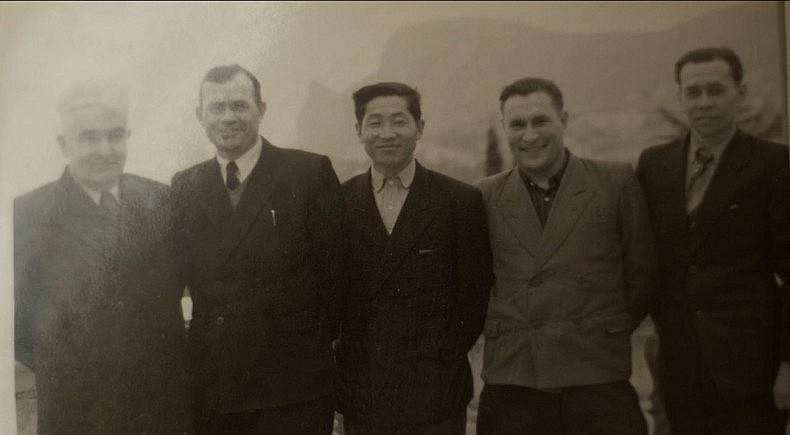

My grandfather (in the center) with his colleagues from the construction bureau. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, little is known about the heavy toll Uzbek Koreans had to pay in order to gain such a high reputation in our society. They were forced to come to Uzbekistan, they had to develop it and turn into their own, they bore children upon it and – very slowly – it became their one and only home.

Nikolay and I are desperate to preserve our history – in the name of all Korean people. This is the story of three generations of his family. It is also my grandfather’s story. Nikolay and I are determined to keep it alive, so the history may never repeat itself.

Soviet Koreans while being deported from the Far East to Central Asia in 1937. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

At least, we truly hope so.

Before 1937

Nikolay’s mother was born in 1919 in Maritime province (Primorsky Krai), in the village called Crabs. Back then it belonged to Posyet national district, and the whole territory of this province was an official part of the Soviet Far East.

In fact, this tiny piece of land – stuck between northeastern China and the upper tip of present-day North Korea on one side, and surrounded with the Japanese Sea on the other – used to serve as a buffer zone for the Soviets throughout most of the 1920s.

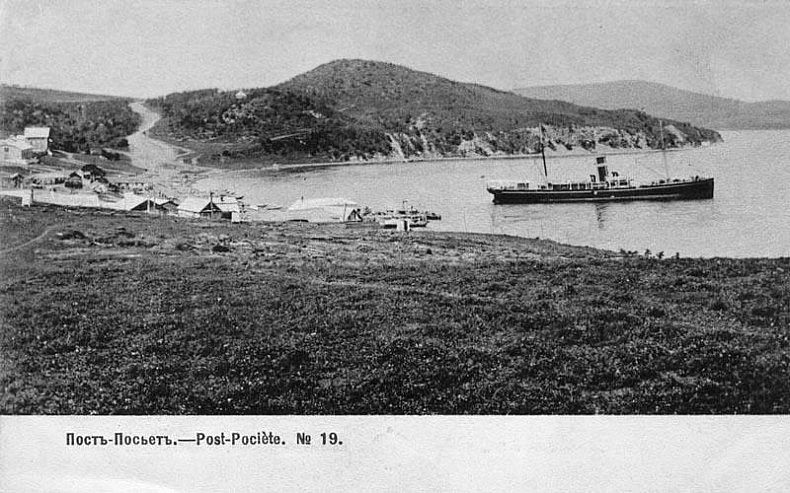

Posyet in the early 1900s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Koreans originally started moving here in the late 19th century, escaping harsh living conditions, poverty and starvation in the north of the Korean peninsula. They built the first Korean villages and towns in the Russian Far East; very often with the agreement of Russian provincial governments and local military forces who desperately needed cheap labor in order to develop this desolated land full of opportunities and natural resources.

Initially, the first Russian settlers in the Far East were quite hostile to unexpected newcomers. Koreans belonged to a different race, spoke an unfamiliar language, ate strange food, and had very different cultural habits.

Korean village near Vladivostok, Russia, at the beginning of the 20th century. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, and in spite of the initial hostility and ethnic discrimination against them, by the early 1900s the number of Koreans populating eastern Russia grew to almost 30,000 from the original 13 families found by a Russian military convoy along the Tizinhe River in 1863.

Subsequently, this number more than doubled after Korea became a Japanese protectorate in 1905 and a Japanese colony in 1910, and more than tripled by the early 1920s. With the Korean peninsula agonizing in a bloody turmoil, more and more Koreans helplessly fled to Russia.

After the Soviet revolution, all ethnic Koreans in the Russian Far East were issued Soviet citizenship. Most of their representations and activities, like local governments, schools, theaters, and newspapers, kept operating mostly in the Korean language.

Many Koreans became active contributors to the Soviet society. Nikolay’s grandfather Vasiliy Lee was one of them. Throughout the civil war in the Russian Far East from 1918 to 1922, he fought together with the Bolsheviks against the Japanese under the command of Sergey Lazo, who later became famous all over the Soviet Union.

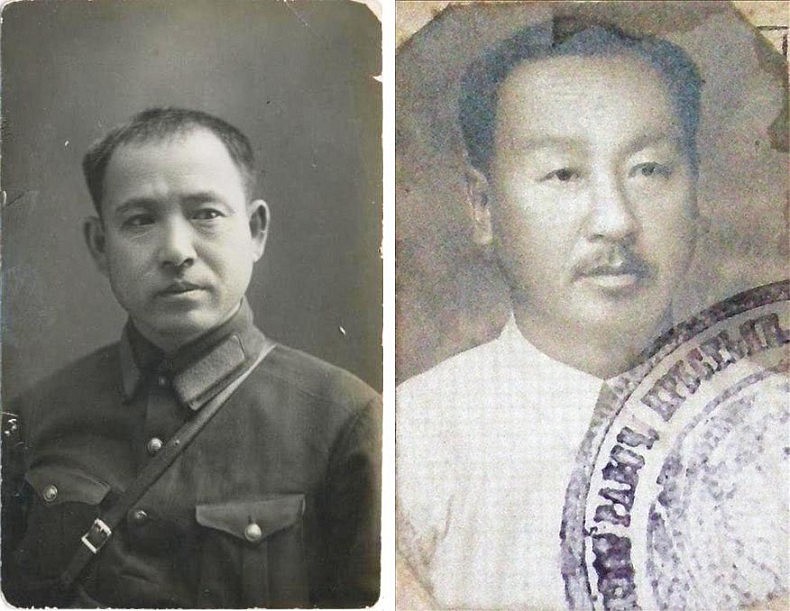

Left: Han Chan Ger, a famous Korean hero of the civil war in the Far East, 1918-1922.

Right: Park Gen Cher, another famous Korean hero of the civil war in the Far East. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, the fact that they truly hated the Japanese, who had colonized and brutalized their motherland, did not spare Soviet Koreans from their “dubious” ethnicity and “dangerous” links to Japan in the eyes of Soviet leadership.

Even before – by the end of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905 – Korean peasants in the Russian Far East were often kicked off the land they had cultivated, with anti-Korean laws applied against them since 1907.

In 1937, shortly after having conducted the official census that counted over 170,000 Koreans living in the Soviet Union in almost 40,000 families, the Soviet government was preparing another ordeal for them, much more horrid in its scope and future implications.

Young Soviet Korean university students in 1934, three years before the deportation. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Check back next week for part two of the series.

Acknowledgments: Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

Please address all comments and questions about this story to [email protected]