This is the second in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Part one is here and part three here.

***

Vasiliy Lee

It was a dark and cold autumn night in 1937. Nikolay’s grandfather Vasiliy, his wife, and three daughters–Nikolay’s then-18-year-old mother Galina and her 24- and 20-year-old sisters–were all at home when someone suddenly knocked the door. They were from the Soviet secret police.

The order was simple and quick: “Gather all your belongings, personal documents, and all food you can find at home in less than half an hour and follow us immediately. You all are being deported.”

This is how it happened. The population of Posyet Korean national district – 171,781 ethnic Koreans from there and the rest of Soviet Far East – were put on cattle trains in a matter of hours at the beginning of the harsh Siberian winter, without much prior notice and with practically no food, water, warm clothes, or personal belongings.

All of them were being sent off to the Soviet Union’s first massive labor camps deep in Central Asia. Galina’s brother, Fedor Lee, was serving in the Soviet military at the time and was not deported with his family. (In part three, we’ll pick up what happened to Fedor).

The train journey was very long and exhausting. It lasted many weeks in dire cold, and the soldiers who guarded the cattle trains shared no food or water with the Korean deportees. In such conditions, people quickly died from malnutrition, and their bodies were left in the snow outside each train station.

During very brief stops at unfamiliar stations, the deportees tried to sell what little they had to locals or simply exchange their meager possessions for food. They also collected snow and melted it into water.

This is how Nikolay’s mother Galina and her two elder sisters survived, thanks to their parents’ ceaseless care and initial food supply from home. Nikolay’s grandparents gave away their own food and water to their three daughters. They didn’t last long and died on that train from starvation and weakness.

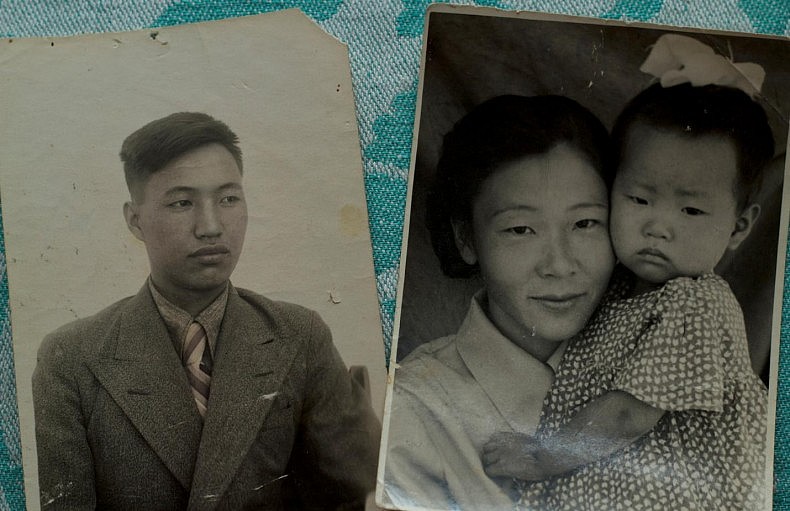

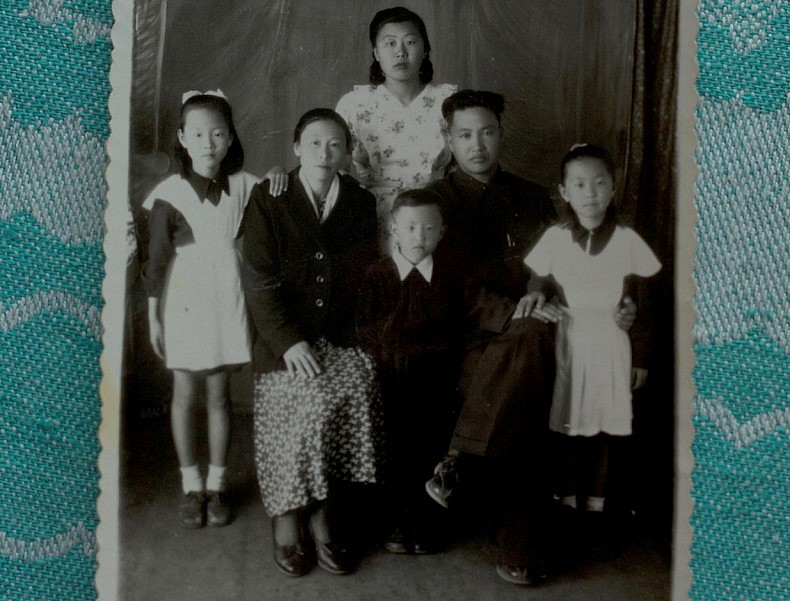

Konstantin Ten and Galina Lee, Nikolay’s parents, with his elder sister. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

Galina and Konstantin

Nikolay’s father Konstantin has also survived the journey, together with his parents and two brothers. He did not meet his future wife on the train. Instead, they met later upon their arrival to Uzbekistan.

When the Koreans arrived, they were lodged in special barracks under 24/7 armed guard. During the day, they worked drying wet swampland and rooting out the cane surrounding Uzbek capital Tashkent back then.

Death was indeed crawling and waiting nearby, but in the form of much tinier creatures. The wet swampland was infested with malaria-ridden mosquitoes and many Koreans – unprotected and with no medicines at hand – got sick and died from malaria.

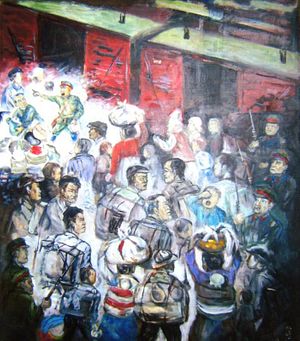

The swampland around Tashkent was first dried and then turned into rice fields. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Nevertheless, in fewer than five years after arriving in Soviet Uzbekistan, all the cane was rooted out and the swampland surrounding Tashkent was made arable. After they had completed this gigantic task, the Koreans were ordered to start growing rice on the new arable land in order to produce agricultural supply for the Soviet state.

All the rice they grew and harvested had to be given to the state. If any were caught trying to hide rice away, they would be judged guilty of collective property theft and go directly to prison.

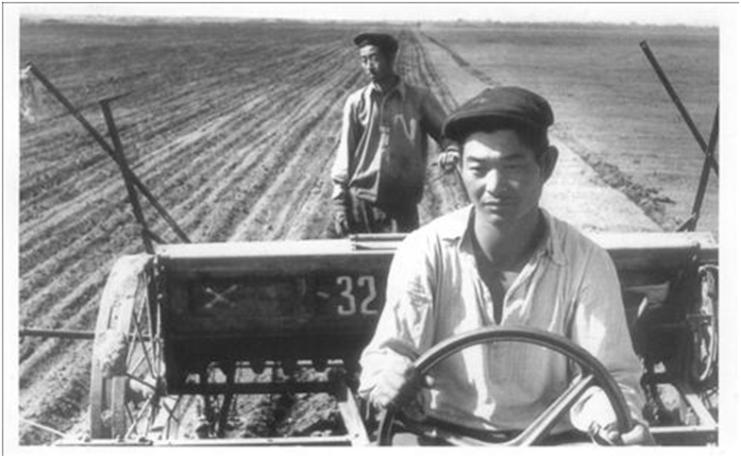

Korean kolkhoz farmers developing the arable land around Tashkent in the early 1940s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The first Korean collective farms or kolkhozes were built around the very same rice fields the deportees had to farm and live on. They lived in tiny houses made of straw and mud instead of initial barracks and shacks.

In fact, they had nowhere else to go. With so many difficulties, they built their first houses and started their families in this foreign place that finally – slowly and painfully – became their own.

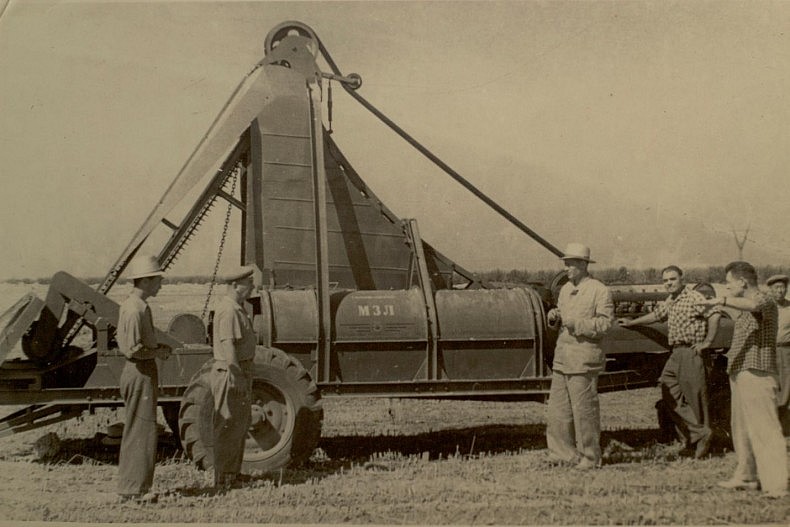

Crop harvesting in a Korean kolkhoz in the late 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

After 1953

In late 1953, the death of Joseph Stalin marked the end of his personality cult and stopped the outright persecution of ethnic minorities. Many of Stalin’s policies were officially declared contradictory to the true principles of Leninism in 1956 and subsequently abandoned by a newly rising political leader, Nikita Khrushchev.

Pardoning all of the Soviet Union’s unwanted people and dissolving the infamous gulags – Siberian prison camps – were among Khrushchev’s first political decisions, taken to attempt to correct the mistakes of a very dark past.

Young and multi-ethnic Soviet citizens in Uzbekistan in the late 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Finally, it looked like the Koreans were given a new chance to become legitimate Soviet citizens. Their children could now go to public primary, secondary, and vocational high schools and local universities. They could also move relatively freely within the Soviet Union and look for better professional opportunities.

Korean students at Nizami’s Tashkent State Pedagogic University. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Paradoxically, most of the Koreans stayed in the very same Korean kolkhozes they or their parents had built. Their living conditions were more stable as the years progressed. These were tight communities where everyone belonged to the same ethnic group and knew each other.

The second generation of proud Uzbek Korean kolkhoz farmers. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Life slowly regained its normality. The first generations of Korean deportees had been trying very hard to forget their dark past, together with all its previous pain. They simply wanted to live happier lives, if not of their own then at least of their children.

A typical Korean family in a kolkhoz after 1956. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

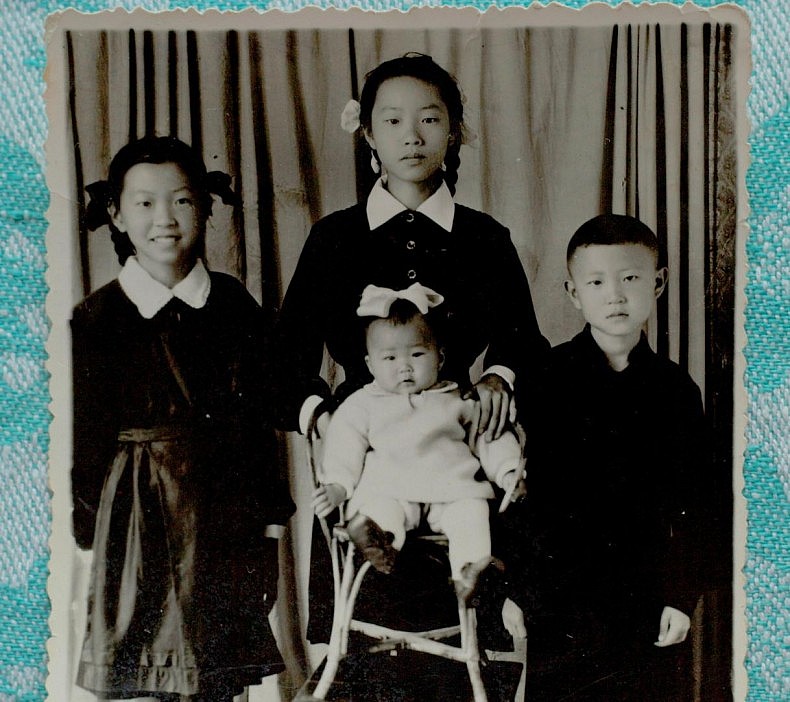

Young Nikolay Ten with his siblings. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Early Memories

Nikolay saw real bread for the first time in his life at the age of five. Before that his mother had always used compressed grass to “bake” bread of some kind. It was so heavy to digest that children often suffered from severe stomach aches, especially after eating a lot of it.

In the early 1950s they lived with constant food shortages: little Nikolay, his mother and two elder sisters (his third sister would be born ten years later).

This is why she finally stopped working in the kolkhoz – there always was plenty of work at home. During the nights and after everyone had left to sleep, she was still awake, secretly sewing clothes, to be sold later to neighbors. All forms of private entrepreneurship were strictly prohibited back then by the Soviet state. Therefore, Galina’s nighttime work had to stay hidden.

Galina Lee with her husband Konstantin Ten and children. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

“I was always playing outside the house as a little boy,” Nikolay remembers very emotionally, “and if I suddenly saw anyone around who didn’t look Korean, I would immediately run back to my mother and shout ‘Inspector is coming, inspector is coming!'”

Galina worked so hard during the day and in her nighttime shifts of sewing, that eventually it took a physical toll. “I had to start drinking cow milk way too early, because my mom was so stressed during the day and so tired of sleepless nights that there was no more milk left in her to feed me…”

Nikolay’s parents’ medals and state awards. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Next week we’ll wrap up the series with the story of Fedor Lee and also the fate of those who heeded the call to return to North Korea in the 1950s.

Acknowledgments: Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by a distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

Please address all comments and questions about this story to [email protected]