Saparmamed Nepeskuliyev was picked up, according to Turkmenistan’s authorities, for possession of banned medications. Salidzhon Abdurakhmanov, if we’re to believe officials in Uzbekistan, was arrested for transporting over 100 grams of marijuana. And Muhammad Bekjanov, said Tashkent, not only failed to keep his slippers “in the proper place,” but was guilty of “incorrectly peeling carrots.” All of them – all of these Central Asian journalists – were, as a result of these spurious charges, jailed or had existing sentences extended.

Central Asian journalists, as the cases of Nepeskuliyev, Abdurakhmanov, and Ruzimuradov illustrate, often work in parlous positions. Four of the five Central Asian states remain in the bottom quarter of Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index, with only Kyrgyzstan, at 85th out of 180 countries, as the outlier. There are few illusions that Central Asia – alongside the Middle East and Southeast Asia – presents one of the foremost regions crushing any forms of independent journalism, ranging from the jailings aforementioned to Kazakhstan’s campaign against non-state media in the American court system.

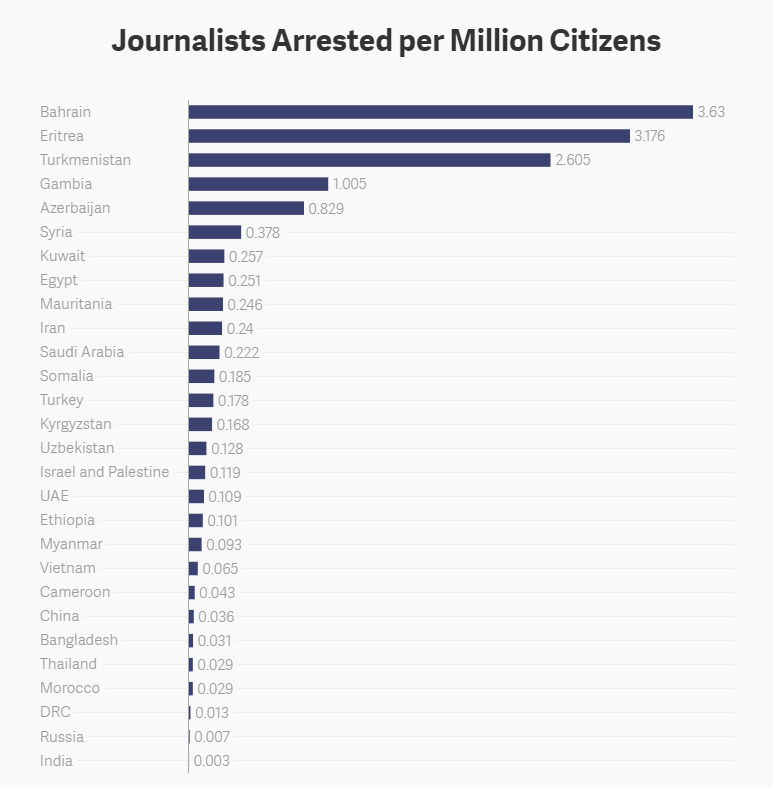

Some new numbers can help shine a bit more light on just how perilous working as a journalist within the region remains. While China and Turkey often, and understandably, swipe headlines for egregious press freedom violations, an examination of journalists arrested per capita can locate Central Asia relative to the other regions known for their efforts to implode an independent press.

Data: CPJ & World Bank, Graph: Casey Michel

According to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists and the World Bank, the two nations with the highest rate of journalists jailed per capita are currently Bahrain and Eritrea, at 3.63 and 3.18 journalists imprisoned per million citizens, respectively. (The data, unsurprisingly, didn’t make it into a recent New York Times op-ed entitled, “It’s Bad in Eritrea, but Not That Bad.”)

Coming in a close third, however, is Turkmenistan, with a rate of 2.61 journalists imprisoned per million citizens. A bit lower on the list, just after Saudi Arabia and Somalia, are Kyrgyzstan (0.17) and Uzbekistan (0.13), at Nos. 14 and 15, respectively. Turkey’s rate remains in flux, but, given the most recent estimates after last month’s attempted coup, the country has likely leaped into the top ten globally. All three Central Asian states notch higher rates than Ethiopia (0.10), Vietnam (0.07), or even China (0.04), while Russia (0.01), and Azerbaijan (0.83, good for fifth in the world) are the only other post-Soviet states to land on the list.

Of course, the rate of journalists jailed per capita is but one facet of examining the press clampdowns – which involve forced exile, rote censorship, and outright intimidation – lacing the region. Indeed, the numbers, if taken alone, can be a bit misleading with smaller countries impacted disproportionately. For instance, according to CPJ’s numbers, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan only have one journalist jailed apiece, while Uzbekistan keeps four journalists behind bars. (None of the three countries come close to China, which leads the world with 49 journalists imprisoned.) So Kyrgyzstan – despite its punchy media environment, especially in Bishkek – manages to clock a higher per capita rate than Uzbekistan, which received the lowest categorization in RSF’s recent rankings. Tajikistan and Kazakhstan, meanwhile, escaped the current list, but opt for other means of suffocating non-state media.

Still, the rates can help place the jailings in a bit more global context, positioned especially against Beijing, Ankara, and Cairo. And if nothing else, the numbers help confirm the region’s substantial challenges for independent media. If there’s any silver lining, though, we can look to the recent movement surrounding the case of Kyrgyzstan’s still-imprisoned Azimjon Askarov. Indeed, next year’s numbers may see certain improvements – for Bishkek, at least.