Over the past few decades of China’s rise, Beijing’s soft power pitch to the developing east has been an indictment of Ugly Americanism. China had fallen victim to Western and Japanese imperialism, and as a result pledged to act not as a patron but a partner in decolonialism and development. In practice that meant that where U.S. diplomacy had traditionally dealt in toxic aid, contingent on political cooperation, China had typically offered infrastructure-for-energy and other business deals.

After Donald Trump’s election to the presidency in the United States, after proposing a ban on Muslim newcomers that his administration indicates is still in the works, some Arab entrepreneurs are already looking to China for answers. “There is hope in the East,” one Arab businesswoman in the United Arabian Emirates told me.

Where Trump has pledged to build walls and other roadblocks to international immigrants and in particular Muslims, China continues to spend a mint building halal restaurants, hotels, mosques, and Muslim cultural venues to welcome neighbors from Central Asia and the Middle East.

The implications are clear: China has long represented an alternative in the global market for influence once dominated by Washington; China had the forethought to make bank on mounting anti-Islamic sentiment in the post-September 11th backlash against international Muslims, making deals few other countries wanted at the time; and China is once again open for business.

But as China’s international clout and economy come to rival — and by some measures, surpass — the United States, Beijing is apparently having trouble differentiating itself from Washington, as far as the Arab World is concerned. Chalk it up to Beijing’s shifting global agenda or a diplomatic coming-of-age.

Saudi Arabia and the Middle East region remain key suppliers of natural oil and gas to the People’s Republic. But after 2011, when China lost millions in the likes of war-torn Libya and Syria, it began to pen a slew of deals with alternative providers, particularly in North America.

And then came the Arab Gulf’s worst nightmare. At a lackluster late-October forum on energy cooperation in Beijing this year, trade officials said Arab counterparts had to “restructure their economies,” China’s state news broadcaster CCTV reported. The incident highlighted the degree to which the relationship had been contingent on energy trade. Amid China’s recent push to diversify the nation’s fuel supply and also crippling fears over consistently plummeting oil prices, the Sino-Arab economic partnership seems strained. How much longer could China and Arab states premise their relationship on a rapidly depreciating product?

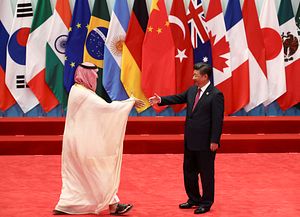

Also late last month, China conducted its first joint counterterrorism drills with Saudi Arabia in the southern Chinese city of Chongqing. It’s been doing the same with other Muslim-majority Asian nations — mostly members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization — over the past few years. But Saudi Arabia’s participation in the drills indicated the first instance of Arab support for China’s controversial bid to pacify insurgent elements among its Muslim ethnic Uyghur minority in the far-Western region of Xinjiang.

The drills were prescient, and not just because Riyadh chose to support a key economic partner over its coreligionists. Beijing hopes to pacify the Uyghurs primarily to facilitate growing energy imports from closer Asian neighbors like Kazakhstan, one of Saudi Arabia’s chief competitors in the race to quench China’s thirst for energy.

The incident highlighted China’s importance to the Saudis — and the lengths to which the kingdom would go to save a struggling marriage. China once seemed to rush to replace the United States as Riyadh’s top oil importer. The tables had turned and Saudi Arabia now seems more eager to pursue the relationship.

Arab politicos and intellectuals have long decried a precarious U.S.-Arab partnership, premised disproportionately on just two things: Ever-fluctuating oil prices and the ebb-and-flow of counterterrorism.

China promised more than that. Since 2013, Beijing had championed its “One Belt, One Road” (一带一路)policy of promoting trade with historical Silk Road trade partners in faraway West Asia. But the rousing slogan hasn’t been met with much innovation in China’s trade agenda. Very recently, even Chinese scholars have begun to characterize the OBOR policy as a means of easing stress on China’s overcapacity production sectors by encouraging them to cater to international countries in need of infrastructure.

Much as China’s foreign affairs and trade officials tout China’s support for Arab states’ independence movements in the 1950s and 1960s at diplomatic affairs, the revolutionary spark is fading. Some things about the American model of foreign affairs are beginning to seem inevitable.

China tried, though.

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Islamophobic sentiment in the United States drove away international business from the Middle East and North Africa. In a high-profile example, in 2006, UAE enterprise Dubai Ports World pulled out of a plan to manage six U.S. ports after U.S. legislators attacked the deal as a potential security risk.

China was there to capitalize on the United States’ lost business opportunities. As early as 2001, Beijing established the Chinese-Arab Friendship Association (CAFA) to promote bilateral relations across sectors.

“The kind of discrimination Muslims faced in the West after 9/11 will have no place in Chinese-Arab relations,” Li Ziran, an organizer of a China-Arab States Economic and Trade Forum — one of many events brokered by China’s new Arab World diplomacy — told World Affairs Journal in 2013.

“Terrorism is irrational, but it is a means of weaker nations fighting against the power politics of stronger nations, so the United States should reflect on its own policies,” Li added — in an indication of how far China had gone to act as a counter to the U.S. discourse on Arab and Muslim nations.

The effects of this burgeoning partnership were astounding. In less than a decade after CAFA’s launch, in 2010, China surpassed the United States as the Middle East’s largest export market and also as the largest importer of Middle Eastern oil.

In the meantime, China built a flurry of projects designed to show its embrace of the Arab world. China used state funds to build an elaborate mosque complex in Guangzhou to welcome Arab and other Muslim-majority Asian nationals to its 2010 Asian Games Event. It’s illegal under China’s socialist constitution to use public funds for religious purposes — but before 2011, the thirst for a Sino-Arab partnership and China’s signature flexibility prevailed. In natural-resource-rich Algeria, Chinese state-owned enterprises signed a bid to build the third-largest mosque in the world, behind those in Mecca and Medina.

China also built infrastructure for exports that were meant to help not just with natural energy trade but also with exports and services across sectors. For example, Chinese state-owned enterprises built Algeria’s East-West Highway — the longest highway in the entire continent of Africa. Corruption allegations over the highway are ongoing.

Chinese-built infrastructure never yielded the desired results in terms of diversification. Gulf countries continue to rely on oil exports. North Africa remains a getaway for European, American, and increasingly Chinese tourists. The reasons are manifold. An absence of venture capital and innovation in Arab economic planning are among the reasons why the infrastructure didn’t revolutionize the Middle East/North Africa region. The China model also wasn’t easily transplanted there — there are labor rights abuses in Arab countries, but a long history of unionization in countries like Algeria, for instance, keeps their population from becoming cogs in a nationwide factory for low-cost production, the way China developed its economy.

Then in 2011, revolution struck in Tunisia and spanned the region. For a China, which had recently made greater inroads into Arab oil markets, the instability amounted to an immeasurable loss of investments and fuel for what was then an even more rapidly growing Chinese economy.

In the years that followed, Beijing would aggressively pursue a battery of multi-million-dollar deals in more stable climes — with energy-rich Central Asian neighbors and, amid the shale boom, across the Americas.

China’s new President Xi Jinping appeared to ramp up visits to oil-driven economies in Latin America and Central Asia.

In February 2013, Chinese national oil giant CNOOC completed a $15 billion takeover of Canada’s oil and gas company Nexen — one of multiple energy deals of that scope in Canada. In Kazakhstan, in September 2013, he penned an $5 billion deal for a share of an offshore oilfield.

The Arab criticism of the U.S. role is that relations are premised almost entirely — and precariously — on oil and counterterrorism. Another criticism is that those relations are almost invariably tied to Washington’s involvement in Arab politics. China, as a growing power, operated explicitly on a policy of noninterference in the politics of its international partners. In the past, that was how a government ostensibly governed by socialist principles was able to do business with some of the world’s most notorious hyper-capitalist kleptocracies and genocidal regimes. For better and for worse. China was a business partner — not an overbearing father-figure, as the United States had been.

The Iraq war ushered in the end of an American pretext for global interference — Washington could no longer convince people that it was advancing democracy internationally. But it’s not just the United States; it seems that the masks of ideology are falling internationally. Because it’s a lot harder lately for Arabs and others to pretend that China’s foreign affairs are governed by anti-colonial revolutionary principle; Beijing appears to have abandoned its principles of noninterference on the way to the top.

In recent years, China has endeavored to enter itself into the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, brokering peace talks and commenting on incremental shifts in the standoff without much enthusiasm from either side (you may not have heard, but China supports a two-state solution). Together with Russia, China notoriously blocked four United Nations resolutions on the ongoing bloodshed in Syria. China’s involvement in both conflicts has provoked the ire of Arab intellectuals internationally, in much the same way they decry U.S. involvement.

Earlier this year, China came out in support of Riyadh in the Saudi-led coalition’s politically charged, devastating bombing of Yemen.

Reporting on China’s business deals in Arab countries just a few years ago, many sources expressed enthusiasm for an alternative to the U.S. model. Even if China’s policies of non-interference were themselves problematic, the Middle East and North Africa enjoyed a marketplace with options.

But as China ascends, the promise of a rising Eastern power is no more. As far as Arabs are concerned, Beijing has done little but reinvent the U.S. model of global dominance.

Massoud Hayoun was most recently a reporter (and often editor) for Al Jazeera America’s website. Before that, he worked for AFP, The Atlantic, and South China Morning Post (in Hong Kong and Beijing).