Five weeks ago, it was announced that Australia finalized a $25 billion-dollar order of anti-submarine frigates from Britain’s BAE Systems. This purchase is the latest procurement of heavy weaponry threatening to stir up the South China Sea territorial dispute.

Since 1991, five of seven countries with a claim to islands or water in the South China Sea have purchased at least one attack submarine, and all five countries that have begun or announced freedom of navigation missions in the South China Sea possess submarines. As the danger of submarines in the South China Sea has grown, countries like Australia have responded by further investing in either submarines or anti-submarine equipment.

The history of submarine usage in combat dates to the American War of Independence when the “Turtle” submersible attempted to plant a bomb on a British flagship. Since then, attack submarines have since been used to disrupt trade routes, secretly deploy troops, and dodge enemy lines to gain an element of surprise. A necessary tool in interstate warfare, submarines have been used to great effect, such as when German U-Boats in World War I sank an estimated 5,000 ships.

The South China Sea is notable for the nearly $5 trillion dollars of annual global trade passing through its waters, billions of tons of crude oil, and a strategic location, potentially serving as an easy point for Chinese submarines to access the Pacific Ocean. While smaller territorial conflicts in the South China Sea have existed since the 1970s, the conflict has seen increasing movement and attention since about 2010, as China began building artificial islands at a greatly expedited rate.

Part of this construction endeavor included building the Yulin-East Chinese submarine base. Maintaining a submarine presence in the region is important to China; already in the South China Sea dispute, submarines have been used for gathering intelligence, projecting power, and deterring hasty military engagement. If ever war should break out, active submarines in the area could prove the difference in the outcome of the conflict. Because of this, it is important to understand the scope and extent of submarine proliferation, especially those possessed by states with a claim to islands or area within the South China Sea.

One issue when analyzing the proliferation of submarines in the South China Sea conflict is that there is no centralized and complete open-source registry of submarine procurements. To ameliorate the uncertainty, I amalgamated data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the Nuclear Threat Initiative, and other open sources to compile a dataset of almost all direct submarine transactions between relevant parties.

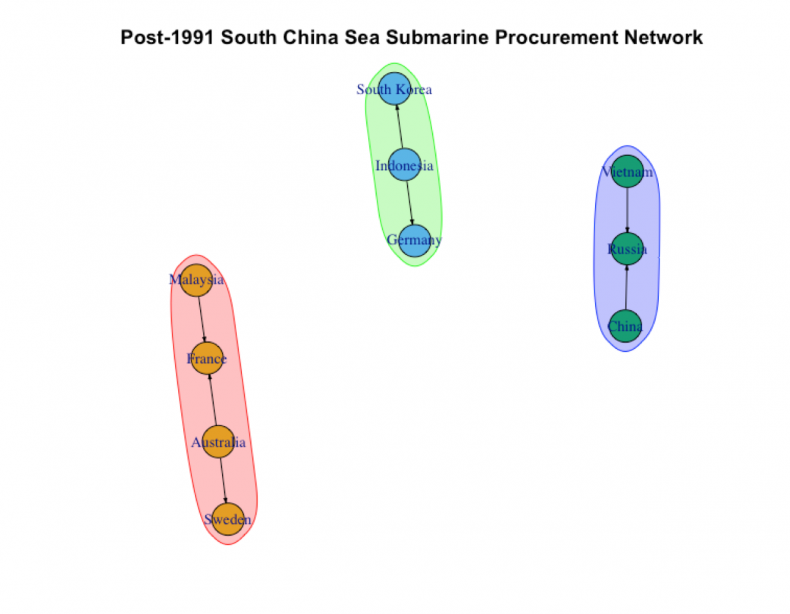

When plotting the claimant states’ submarine procurement networks since 1991, three distinct networks emerge.

Most notably, Russia has supplied both China and Vietnam, which have competing claims in the South China Sea, with submarines. Around 2014, Vietnam ordered about six Kilo-class submarines from Russia, of the same vein as the eight diesel-electric Kilo-class submarines that China ordered in 2002. And as reported by The Diplomat, the Philippines, another claimant country involved in the South China Sea dispute, has recently made news for potentially seeking to procure submarines from Russia as well. While China has indigenous production capabilities, boasting Jin-class nuclear submarines in its naval arsenal, other countries possess similar non-nuclear submarines just by procuring from the same developer.

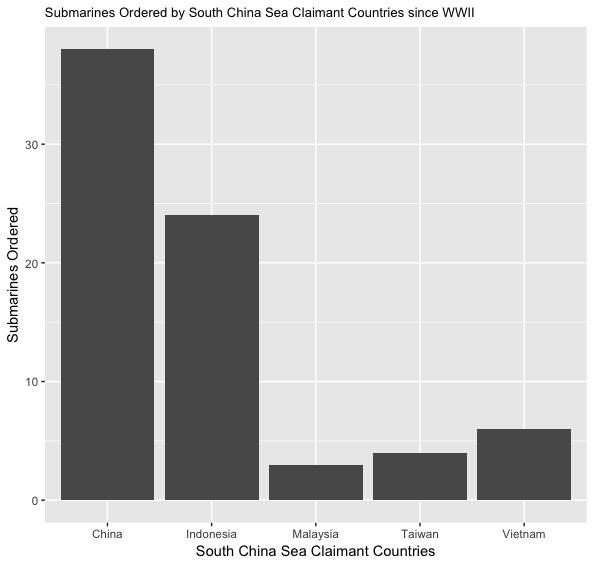

Since World War II, China has been the largest procurer of submarines, ordering more than 35. This total, however, does not include its indigenously-produced submarines. Some submarines have been retired over time, but it appears like the Chinese submarine fleet includes 48 operational diesel submarines, and 10 to 13 nuclear submarines. Indonesia also boasts a large submarine fleet – while Indonesia operates far fewer submarines now than it did during the 1960s and 1970s, it currently maintains a fleet of five submarines and has announced a plan to increase its fleet to eight by 2024.

The claimant states’ submarines aren’t the only ones in play: the United States, Japan, Australia, United Kingdom, and France have all begun or announced freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea. These patrols are aimed at curtaining China’s reach and bolstering support for allies in the region. The large number of state parties, however, increases the chance of an accident or provocation. Forays into China’s claimed exclusive economic zone have already drawn the ire of Chinese state and military officials. And accidents have occurred, such as the collision of a Chinese submarine with a U.S. sonar array in 2009.

The destructive potential of submarine proliferation in the South China Sea is clear to military observers, and states have begun preparing accordingly. The United States and Japan in March began conducting anti-submarine warfare drills, and China has notably been planting underwater listening devices in hopes of keeping track of other countries’ submarines.

Even with these preventative measures, however, the heavy weapons buildup, including Australia’s recent order of anti-submarine frigates, is likely to continue. If tensions rise, it is possible that we will see continued submarine procurements by the claimant states: Brunei, China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

Tyler Headley is a research assistant at New York University. His work has previously been published in magazines including Foreign Affairs and The Diplomat.