On August 15, top Japanese political figures visited the Yasukuni Shrine, a war-linked shrine that houses the spirits of over 2 million soldiers and civilians who died in Japan’s wars. But this year, the scene was noticeably emptier than ever before.

It was a rainy Sunday morning, and visiting were four cabinet members, including Environment Minister Koizumi Shinjiro and Education Minister Hagiuda Koichi. Former House of Councillors Vice President Hidehisa Otsuji went on behalf of the Association of Members of Parliament to Visit the Yasukuni Shrine Together, an organization of lawmakers who used to go in groups numbering 100. Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide was not present, but arranged for a Shinto offering to be sent to the shrine with his own money. Only about 15,000 other visitors were present, nearly a third of the count in 2018.

The day marked the anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II, known as Victory Over Japan Day. It has long been a tradition for political figures to visit the shrine despite the political drama it generates every year. Celebrities have recently been caught in the crossfire as well. In February, Japanese voice actress Kayano Ai angered Chinese netizens when she shared that she had visited the shrine. Two days before the visits this year, Chinese actor Zhang Zhehan issued an apology on Weibo after he was discovered to have gone in 2018.

The Yasukuni Shrine comes to the fore at this time every year. Cabinet ministers and Diet lawmakers visit on the anniversary, and the Chinese and South Korean governments issue statements swiftly after, the former typically being substantially stronger in language. This year, China described the visits as a “challenge to human conscience and international justice,” while South Korea expressed “deep disappointment and regret.” Some have claimed that these visits are evidence that Japanese nationalism is on the rise. Just what is so significant about the shrine anyway?

“Big French circus on the grounds of Shōkonsha” by Utagawa Hiroshige, 1871

Background of Yasukuni Shrine

The Yasukuni Shrine began as a local spirit-inviting shrine or shokonsha that had no affiliation with Shintoism. In 1879, in the aftermath of armed conflict between former samurai of the Tokugawa bakufu and the central government, Tokyo Shokonsha was designated a government Shinto shrine for the souls of fallen soldiers who died for the emperor. Soldiers were ceremonially enshrined as glorious spirits, the highest honor that can be bestowed upon a citizen who died for the country.

The shrine became more known among Tokyoites as a place for entertainment, especially during its spring and fall festivals, showcasing sumo tournaments, horse races, and snack stalls among others. But this began to change during the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars, during which exhibits and celebrations began to cultivate a militaristic flavor in order to shape the collective understanding and memory of the state’s imperial conquest. The souls of soldiers and civilians who died in WWII were enshrined there as well.

Despite claims that the shrine is simply a place to pay respects for the war dead, Professor Takahashi Tetsuya of Tokyo University says that the shrine honors the deceased as gods, rather than mourning them, by framing their deaths as noble sacrifice for the nation. It neglects the reality that a large proportion of soldiers died not in battles but from starvation; it ignores the fact that some civilians enshrined were killed at the hands of the Japanese military (some by means of mass suicide). Its priests have refused to remove the names of certain soldiers who were forced to fight for the empire at the request of bereaved Korean and Taiwanese citizens.

If officials really wanted to pay tribute to the dead, the tomb of the unknown soldier at the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery would appear to be an appropriate alternative, and it is for this reason that visits to Yasukuni Shrine by officials are typically interpreted as political acts. Conservatives are pressured to visit by interest groups, in particular the Izokukai or Association of Bereaved Families, which has an electoral strength of 570,000 (though it’s at half of its 1967 strength).

To outsiders, visits to the Yasukuni Shrine represent a troubling form of historical amnesia that is associated with the denial of war responsibility, and opponents often point to the shrine’s quiet enshrinement of 14 class-A criminals in 1978 as evidence of this. Condemnation has been particularly vocal from China and South Korea, which bore the brunt of Imperial Japan’s attacks and atrocities.

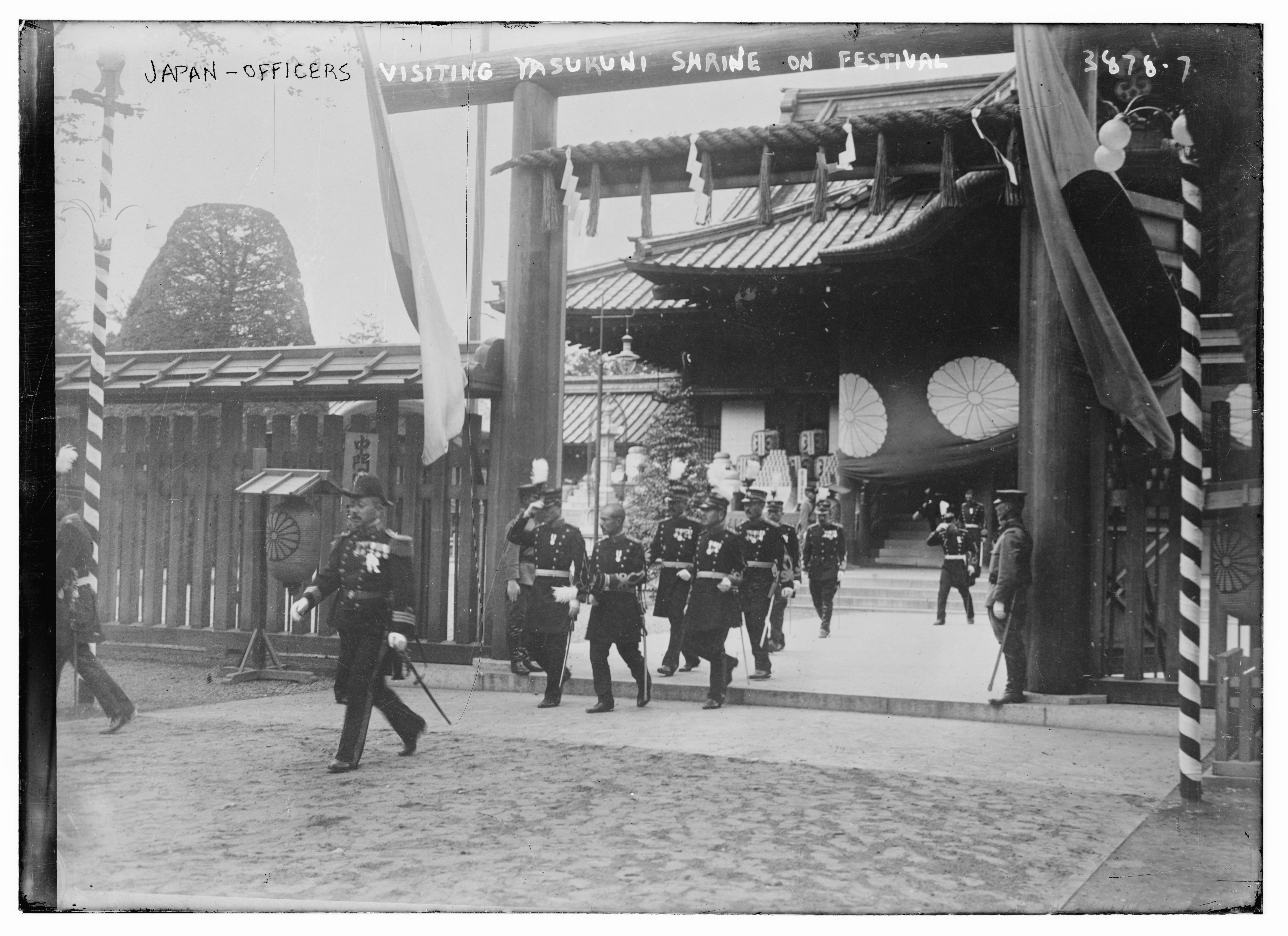

”Japan – Officers visiting Yasukuni Shrine on festival” by Bain News Service, 1915-1920

Yet, the Shrine did not gain international notoriety until 1985, when Nakasone Yasuhiro became the first post-war prime minister to make an official visit on August 15, and paid for offerings using public funds. Inextricably tied to the visit was his push to remove the 1 percent GDP ceiling on defense spending. His visit became a symbol of the country’s potential return to wartime militarism, igniting anti-Japanese protests across China.

Claims of “rising nationalism” also cite the obliging of schoolteachers to sing the national anthem, Japan refusing to compensate “comfort women,” exasperation toward repeated demands to apologize for WWII, and lately characterizing those opposing the Olympics as “anti-Japan.” Nationalism is exemplified by conservative groups like the Nippon Kaigi that advocate for Yasukuni visits, whose members make up a substantial part of government cabinets, and of which Suga and former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo are members.

Are Visits A Sign of Rising Nationalism?

How does this year’s visit compare to the past? Since Abe’s visit in 2013, neither Abe nor Suga have visited in person, and both have opted to send cash offerings instead. Former Prime Minister Koizumi Shinjiro visited six times (once on the anniversary), and Nakasone went a whopping 10 times during his tenure (thrice on August 15). But since Nakasone’s debacle, all prime ministers make clear they are visiting in a private capacity.

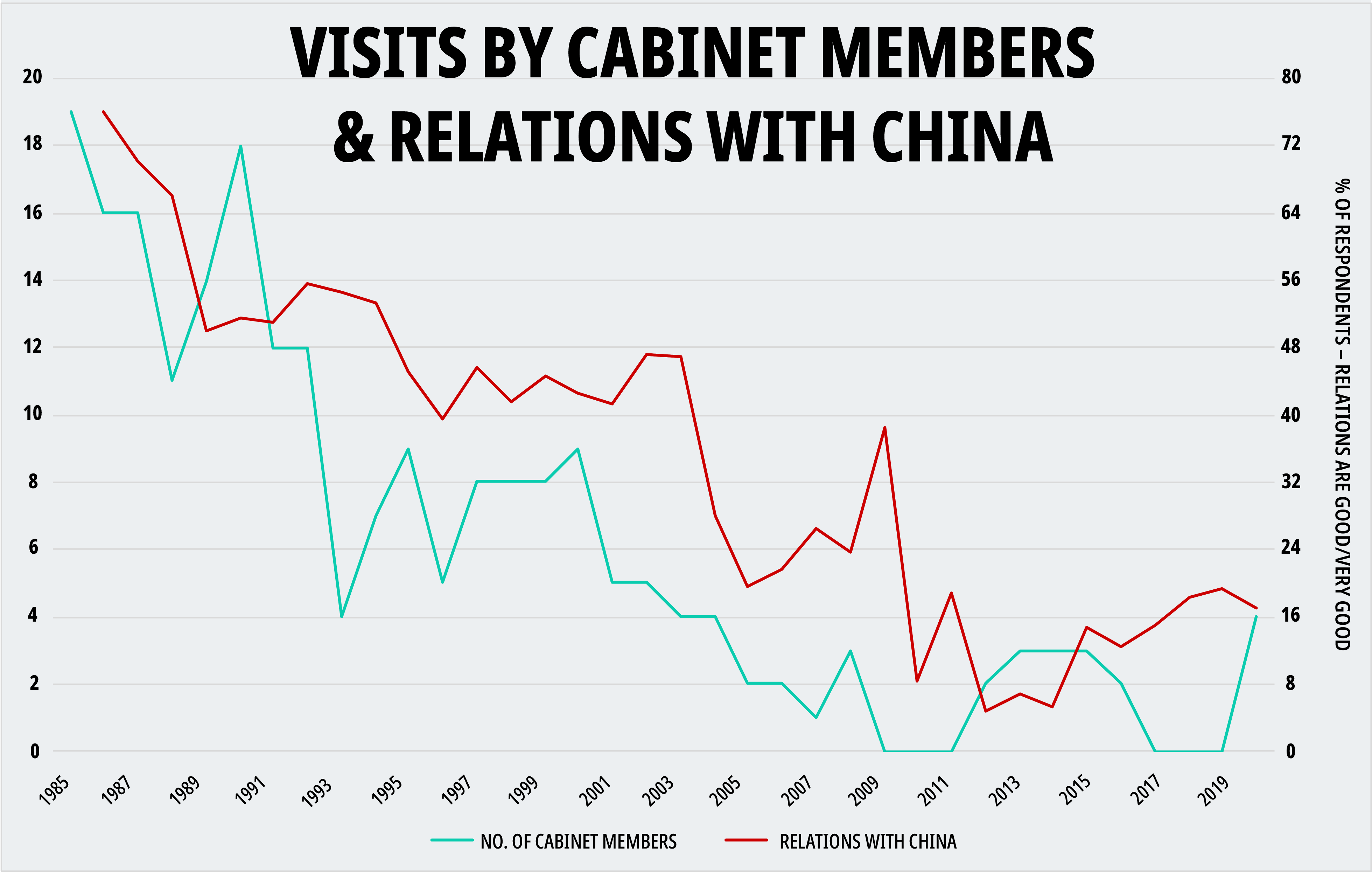

Source: Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, and Japan’s Cabinet Office

In terms of cabinet members, visits on August 15 have decreased significantly since Nakasone’s visit in 1985. In general, as relations with China worsened, the number of Cabinet members visiting on the anniversary decreased. It is likely that ministers have generally chosen not to visit to avoid upsetting China, but the decrease could also be a result of reduced importance attached to visits, as the incumbent generation of ministers were mostly born after the war. Interestingly, this relationship flips from 2013 onwards, making the Abe and Suga cabinet trend-breakers, and could be indicative that (presumably) endorsed visits of their close aides are now used to signal national resolve toward other countries.

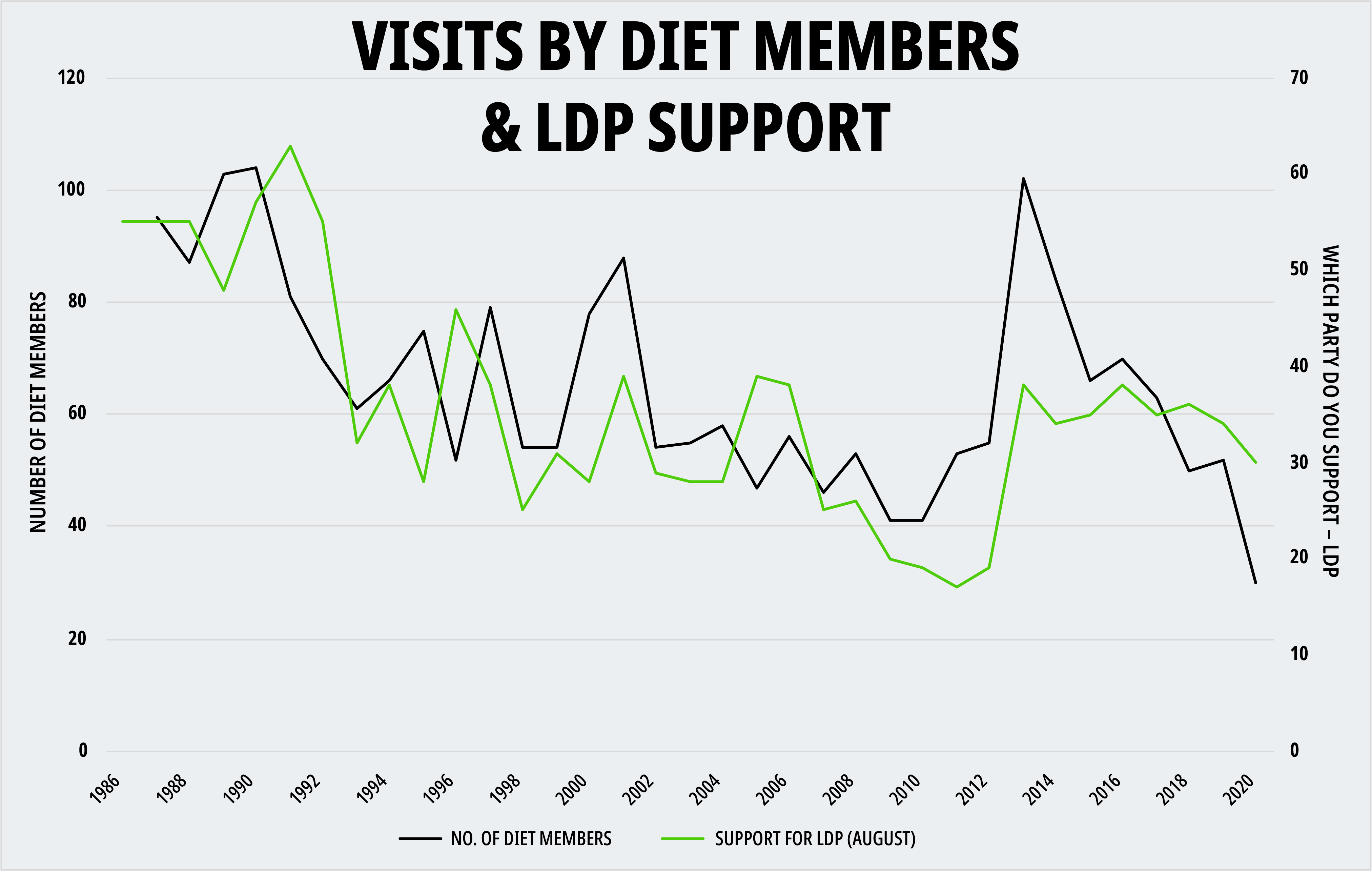

Source: Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, and Mina Erika Pollmann

Visits by Diet members under the supra-parliamentary group have also decreased, and are rather affected by their popular support. When support is high, LDP parliamentarians are likely to worship together to demonstrate solidarity to their voters and supporting interest groups. In addition, the parliamentary group that conducts these large visits comprises only elected officials, and thus the size of the visiting group is proportionate to the number of seats it has in the Diet. Relations with other countries have no effect as parliamentarians are not burdened with commitments to the international arena as Cabinet members are, and place more importance on appeasing their voter bases.

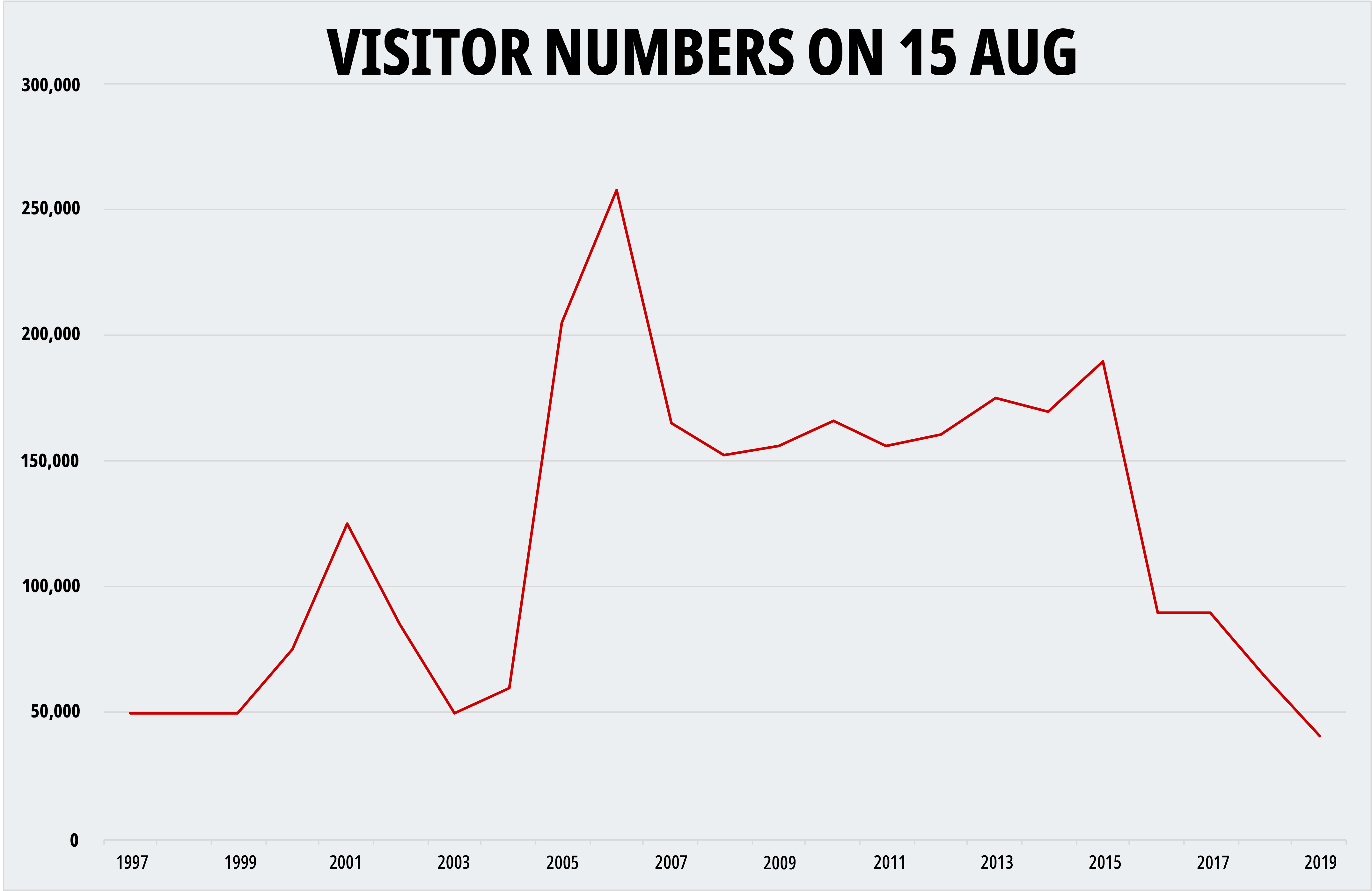

Source: Yasukuni Shrine via Tokyo Shimbun

One might suggest that the low visitor turnouts this year are a result of lockdown restrictions, but numbers have been dropping since 2015. The numbers peaked during Koizumi’s tenure, during which his forthright attitude toward his visits generated a lot of media attention. Notably, he described such visits as being part of Japanese culture and thus visited the shrine every year of his prime ministership – and by 2005, Chinese government officials outright refused to meet with Koizumi over this issue.

While most of the public isn’t opposed to visits by political figures, they are sensitive to the diplomatic backlash. During Koizumi’s tenure, the majority of respondents polled by Asahi Shimbun approved of his visits during his first year, but support dipped over time as the conflict with neighboring countries became gradually more intense. In the months leading up to his resignation, the majority of the public indicated that they did not believe the next prime minister should visit the shrine.

Yet, there is still a pertinent “frustration” against China’s and South Korea’s denouncement of visits, as visible in 55 percent of respondents agreeing that Japan should not take criticism from China and South Korea seriously in a 2014 Asahi Shimbun survey. This can be partly explained by the fact that 64 percent of Japanese people see the shrine as merely a place to commemorate the war dead, as opposed to 12 percent who see it as a symbol of militarism.

Conservative politicians, and more recently the Abe and Suga governments, have aggressively tried to cultivate nationalism in the public, manifesting this ideology through visits to the Yasukuni Shrine with the objective of signalling resolve against China and ensuring support from right-wing groups like the Izokukai. But considering the decrease in visits to the shrine by officials, politicians, and members of the public, if nationalism is really on the rise, it is not to be found here.

What About Other Metrics?

Of course, there are other ways of gauging nationalism, and one that is used most frequently is Japanese perceptions towards China (and South Korea, but mostly China). As a result of China’s behavior toward Japan, including anti-Japan protests, the dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, demands to not visit the Yasukuni Shrine, China has become the “other” to the Japanese “self” – supposedly stirring “reactive nationalism” created out of a sense that the nation’s autonomy is being threatened. But nationalism is more than just animosity toward another country; it requires shared identity.

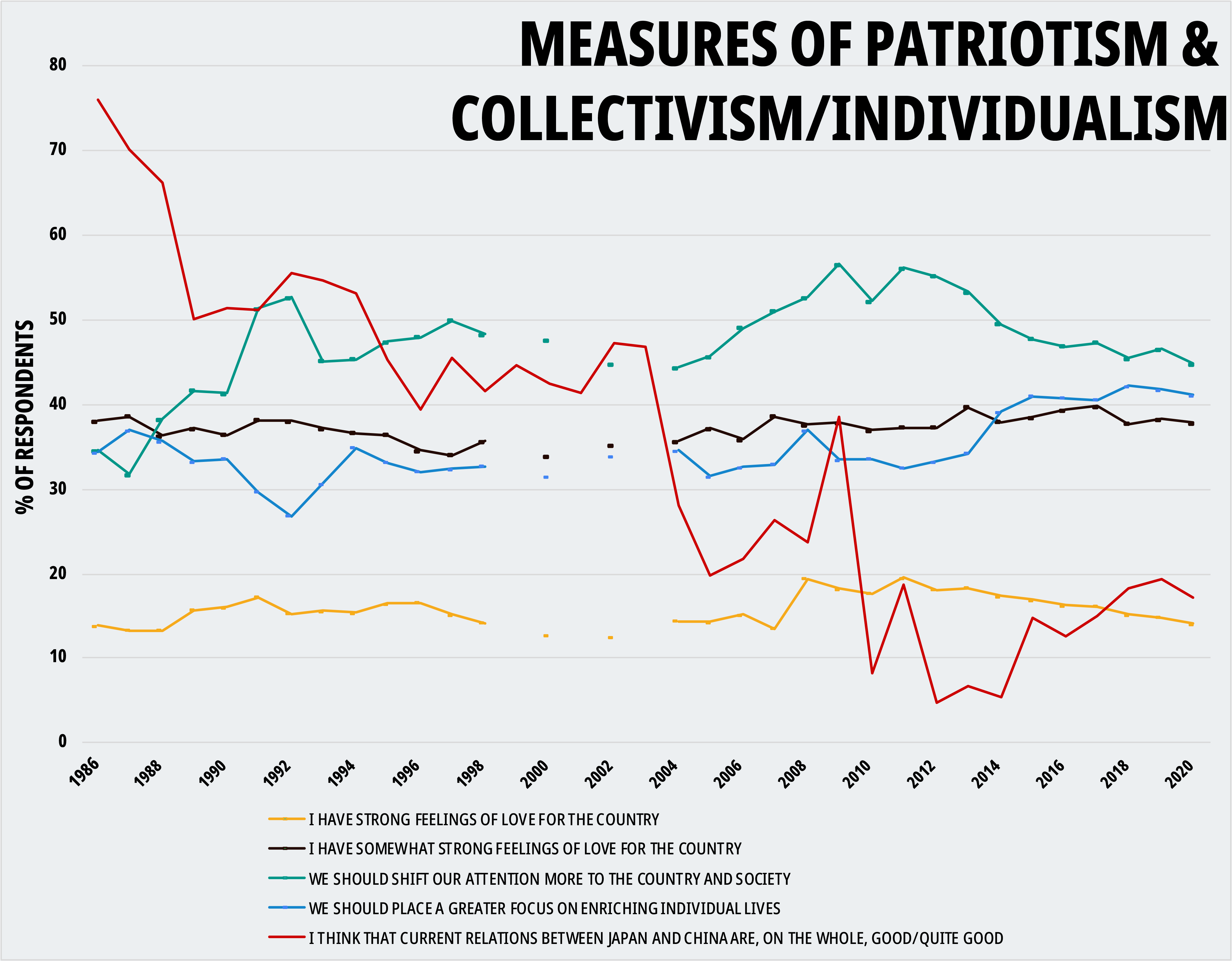

Source: Japan Cabinet Office

If we look more directly at the concept of national pride, we find that levels of “feelings of love for the country” have remained fairly constant since the deterioration of China-Japan relations. Moreover, there has been an increase in those who believe more attention should be placed on individuals as opposed to wider society – what is essentially the opposite of nationalism. When asked about what they take pride in, the top responses given by Japanese citizens were “good public safety,” “beautiful nature,” and their “long history and traditions.” National unity was only selected by 9.5 percent of people.

In terms of citizenship, a 2013 survey on national identity found that while 88 percent of Japanese citizens would rather be a citizen of Japan than any other country, only 18 percent of people agree the country should be supported even when it’s in the wrong. When asked what qualities are important to being a national, 76 percent said that one has to be able to speak Japanese (a 2 percent drop from 2003) – but this statistic actually ranks bottom-two relative to the other countries surveyed (e.g., it’s 96 percent for the United Kingdom). Another survey last year even revealed that 70 percent of Japanese people believe it is good to allow more foreigners into the country.

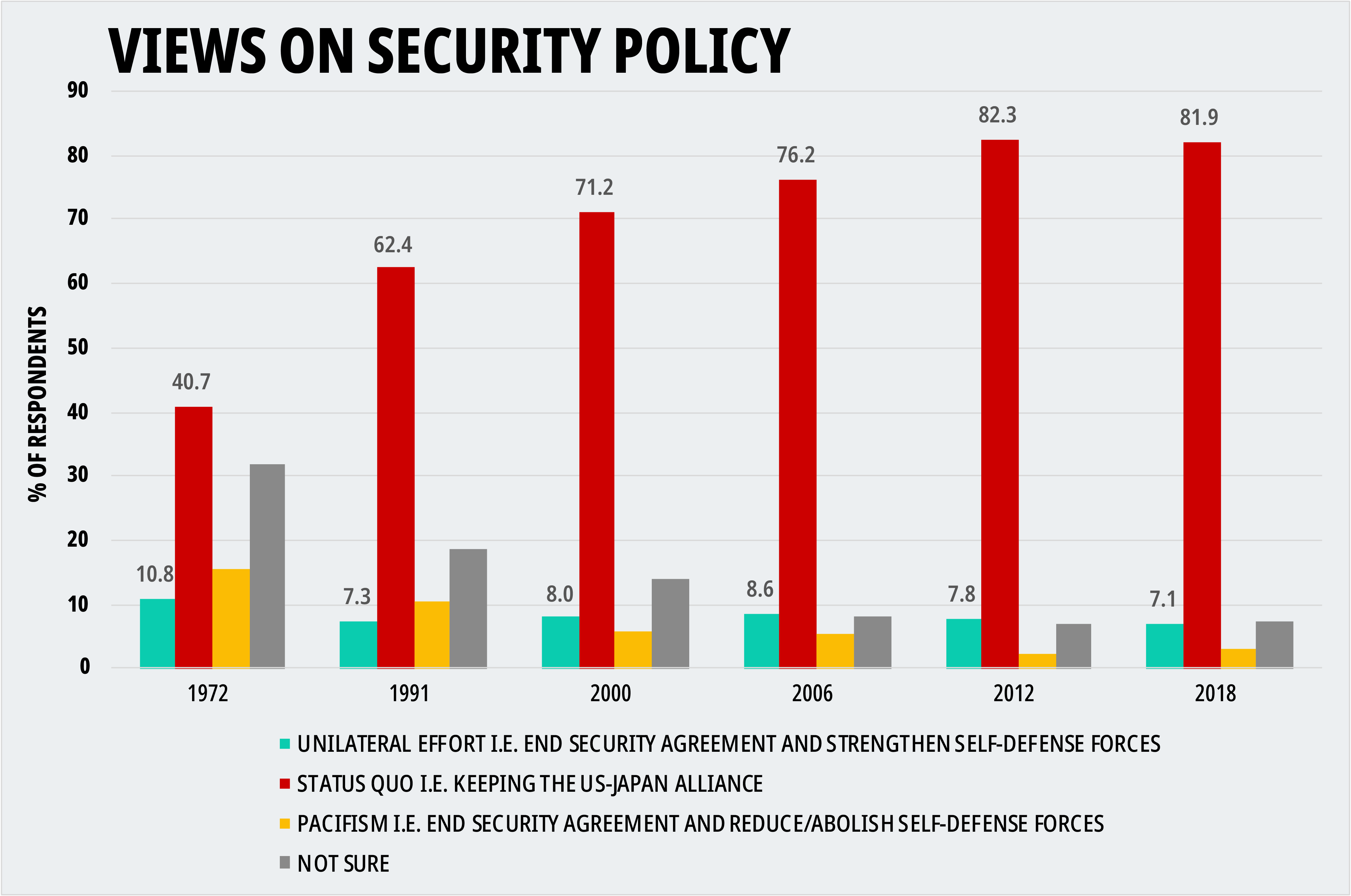

Source: Japan Cabinet Office

It has also been put forth that decreasing support for pure pacifism and increasing support for Japan’s current security alliance with the United States indicates rising levels of nationalism. But the decrease in support for a “unilateral effort” is just as notable. If anything, this only demonstrates that the public has a better sense of its international standing and its need to rely on the United States (though it is framed as an alliance).

What these statistics show is that nationalism is ultimately, as aptly put by Professor Jeff Kingston of Temple University, only the act of “one hand clapping.” Politicians lament the lack of patriotism in the populace and believe they need to rekindle nationalist spirit, and to realize that ambition, they will continue to visit the Yasukuni Shrine at the expense of angering their East Asian neighbors.

Special thanks to Sebastien Fung for the indispensable help and guidance, as well as Aka Heung and Sherry Wong for their generous assistance with the research and translations.