With elections coming up next month amid the messy blocking of former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s nomination, electoral politics in Pakistan remains embroiled in tense contestation. However, in the backdrop remains the ever persisting and foreboding shadow of the most important political player in the country, whose hands are methodically tampering with the various levers of the political machine – the military.

This has been the case for decades. Every contested dissolution of government or Parliament, every instance of disproportionate judicial suppression, every controversial proclamation of martial law – they all tie back to the military in one way or another. This renders the idea of a deep state pertinent.

In essence, the much theorized “deep state” can be broken down to any non-elected (and thereby non-accountable) entity that remains excessively embedded in the political functioning of a state, regardless of who wins elections or is officially accountable to citizens. Some think of the deep state as being associated with preeminent bureaucratic influence, as in the United States, while others see it as the growing religious vigilante groups in some polarized countries. However in Pakistan’s case it would be accurate to point to the military as being central to the deep state.

How did we get here? Some would argue that this has been the case since the very beginning, particularly facilitated by military rule under Muhammad Ayub and Yahya Khan in the 1960s. However, a compelling case can be made that the true cementing of the military’s power resulted from a story of militarization, Islamization, and international coalescence alongside the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

How the Soviets in Afghanistan Posed a Threat to Pakistan

Tumultuous political dissatisfaction throughout the 1970s resulted in the 1978 communist revolution in Afghanistan. However this would not signal an immediate bright new era for the country, as bad land reforms and alienation of tribes as well as the urban middle class, led to a crisis on all fronts.

At the forefront of this were the Mujahideen, employing classic strategies of guerrilla warfare while sheltered in the hills. Unable to cope, the Afghan government turned to the Soviets for assistance. The expansionist flavor of the Cold War spirit made the Soviets all too ready to intervene, intent on propping up a puppet regime under Babrak Karmal in Kabul.

The Soviet military rolled into Afghan territory, brutally cracking down on dissident populations while planes carpet-bombed entire towns. Huge streams of Afghani refugees fled across the border to Pakistan. While this put significant economic pressure on Pakistan, there was also an underlying security connotation – a veiled threat that they might be next in line for a red takeover.

The Soviets had a three-fold aim, which included neutralizing Pakistan’s security strategy (potentially by inciting separatist sentiments in Balochistan), disrupting a potential alliance with the United States, and accessing the Arabian Sea to improve their naval power. Thus, Pakistan was directly facing the bleak possibility of facing a similar situation as Kabul, unless they could act quickly and decisively on the security front.

Islamabad’s response to this was very much shaped by its own domestic political circumstances. After all, Pakistan happened to find itself at a transitional phase. Although relations with Afghanistan had been historically iffy because of disagreements over the Durand Line, it would ironically be the events unfolding in its neighbor that would give Pakistan’s military the impetus to once again sniff out an opportunity at re-establishing dominance.

Pakistan’s Response: Islamization, Militarization, and a Revitalized Deep State

Following its defeat to India in the 1971 war, and the resulting loss of East Pakistan (now the independent country of Bangladesh), the Pakistan military had undoubtedly waned in popularity. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s civilian government had actively taken measures to diminish the military dominance in politics, by reducing military expenditure, attempting peacebuilding through the Shimla agreement with India, and maintaining his own paramilitary Federal Security Force to counterbalance potential intimidation by the army.

The military, however, would see a resurgence soon enough, when Gen. Zia-ul-Haq led a coup to overthrow Bhutto in 1977 (and eventually execute him). At this point the 1971 defeat remained relevant for a couple of reasons, the first being a persistent undercurrent of humiliation inadvertently spurring a determination for military redemption, and the second being a more conscious concern toward the potential security threat posed by India.

At this point Pakistan was also playing host to over 386,000 refugees who had migrated from Afghanistan due to the domestic crisis, with the Soviet invasion simply exacerbating this influx. This refugee crisis came at a great cost to the hosts now attempting to combat rising property prices and ecological degradation caused by immigrants. Thus, economic issues were piled onto the preexisting issues revolving around security and diminished foreign support in Pakistan.

In light of all these factors, Zia saw the Afghanistan crisis as the perfect backdrop for Pakistan’s military to regain some of its lost swagger.

Two features of Zia’s regime appear prominent in hindsight: Islamization and militarization. Both of these were on display in his response to the Afghan invasion by the Soviets. Most notably, Pakistan extended support in material, technical, and financial terms to the Afghan Mujahideen. This served to be beneficial on numerous counts.

For starters, the United States was naturally keen to get involved in countering the ideological influence of the Soviet-supported communist regime in Afghanistan. However, this was proving difficult because of the complicated logistics. By contrast, the USSR shared a lengthy border with Afghanistan via the then Soviet republics of Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. A full-blown military intervention by the U.S. military also seemed like an unlikely choice, given the outcry from the American public, which that had forced the government to pull troops out of Vietnam the decade before.

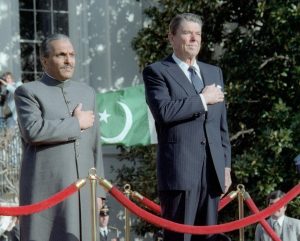

By promptly and vociferously positioning Pakistan as a “frontier state” in this conflict against anti-Islamic communist values, Zia gave the Americans exactly the window of opportunity they needed. Pakistan became the intermediary for the U.S. and Saudi Arabia to funnel aid to the Mujahideen and associated insurgent groups, facilitating their attempts to destabilize the Soviet presence. This became a sustained pattern throughout the course of Central Intelligence Agency’s “Operation Cyclone.”

Thus U.S. support to Pakistan was galvanized in light of their cooperation in propping up the Mujahideen, and also in collectively endeavoring to strengthen Pakistan’s own military to deter the Soviets from invading Pakistan next. Declassified documents demonstrate this strategic outlook within U.S. security circles at the time.

This approach of supporting the Mujahideen marked a realization for the Pakistan military that training and employing such non-institutional insurgent groups as strategic assets was indeed pragmatic, and could be extrapolated to fulfill other security aims, as evidenced in the support of militant outfits in Kashmir. The military also became cognizant that their influence could be exerted even through more implicit means.

Over the course of the conflict, the military also simultaneously persisted in increasing its grasp over domestic politics, with frequent use of measures like martial law weakening any opposition. Eventually, the contribution of Pakistan in inflicting heavy damage on the interventionists served as an efficacious means of proto-legitimizing the military. They were now increasingly viewed as preeminent in combating the double threat posed by India to the southeast and the Soviets from the north.

With this seemingly newfound credibility, Zia sought to further centralize authority by amending the 1973 constitution, to essentially prevent liberal actors from challenging him. The eighth amendment of 1985 permitted the president to dismiss the National Assembly unilaterally. This was an essential tenet of facilitating the deep state, as even after Zia’s death, presidents under military influence would frequently dismiss democratically elected governments that attempted to undermine the army’s influence.

And so it goes. Even though elections were held throughout the 1990s, Pakistani politics has remained constantly marred by military intervention, frequently compromising the constitutionally aspired trias politica balance between the executive, legislature, and judiciary. This influence has been direct, as seen under Pervez Musharaff, or more indirect, as seen in the country’s frequent executive instability. Thus, a cascading effect following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan has led to the inadvertent entrenchment of a military deep state in Pakistan.