In 1998 photographer Kevin Bubriski spent a time among the Uyghurs in Kashgar, their ancient capital city in the Xinjiang region of China. His photographs are a glimpse into the lives of a people whose city and culture have been forever altered by repression under China’s President Xi Jinping.

The Xinjiang region of China, known officially as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), in the country’s far northwest is home to about 12 million Uyghurs, a mostly Muslim ethnic group. The Uyghurs speak their own language and are ethnically and culturally closer to the people of Central Asia than they are to the Han Chinese.

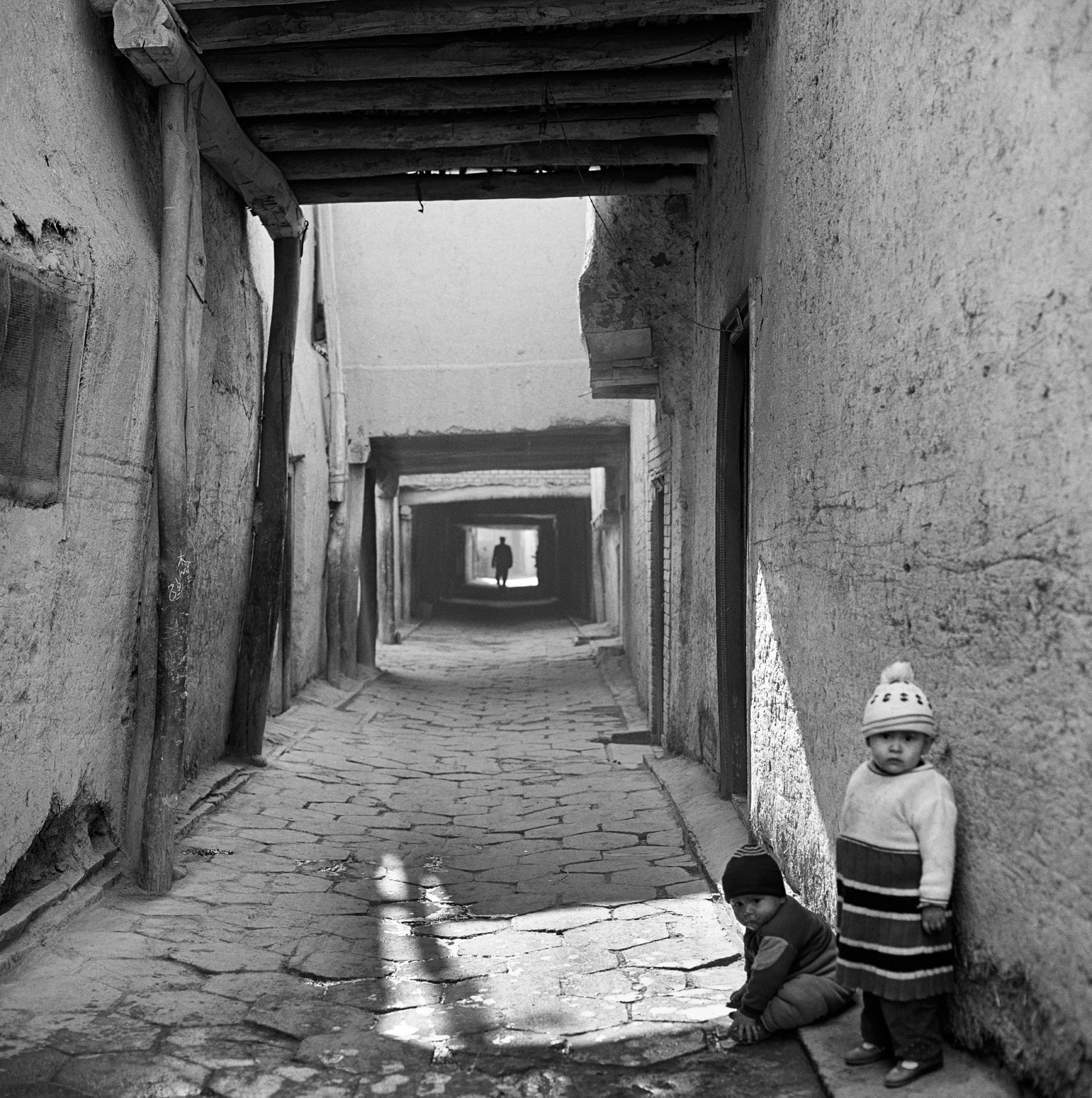

Residential neighborhood in the old city before demolition. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

For decades, various Chinese leaders in Beijing have worked to undermine the Uyghurs in Xinjiang by encouraging Han Chinese to move to the province in the hopes of diluting the Uyghur population. This has resulted in the Uyghurs now making up less than half of the region’s population.

But with the rise of President Xi Jinping in 2013, and his consolidation of power, the situation of the Uyghurs has become even more dire.

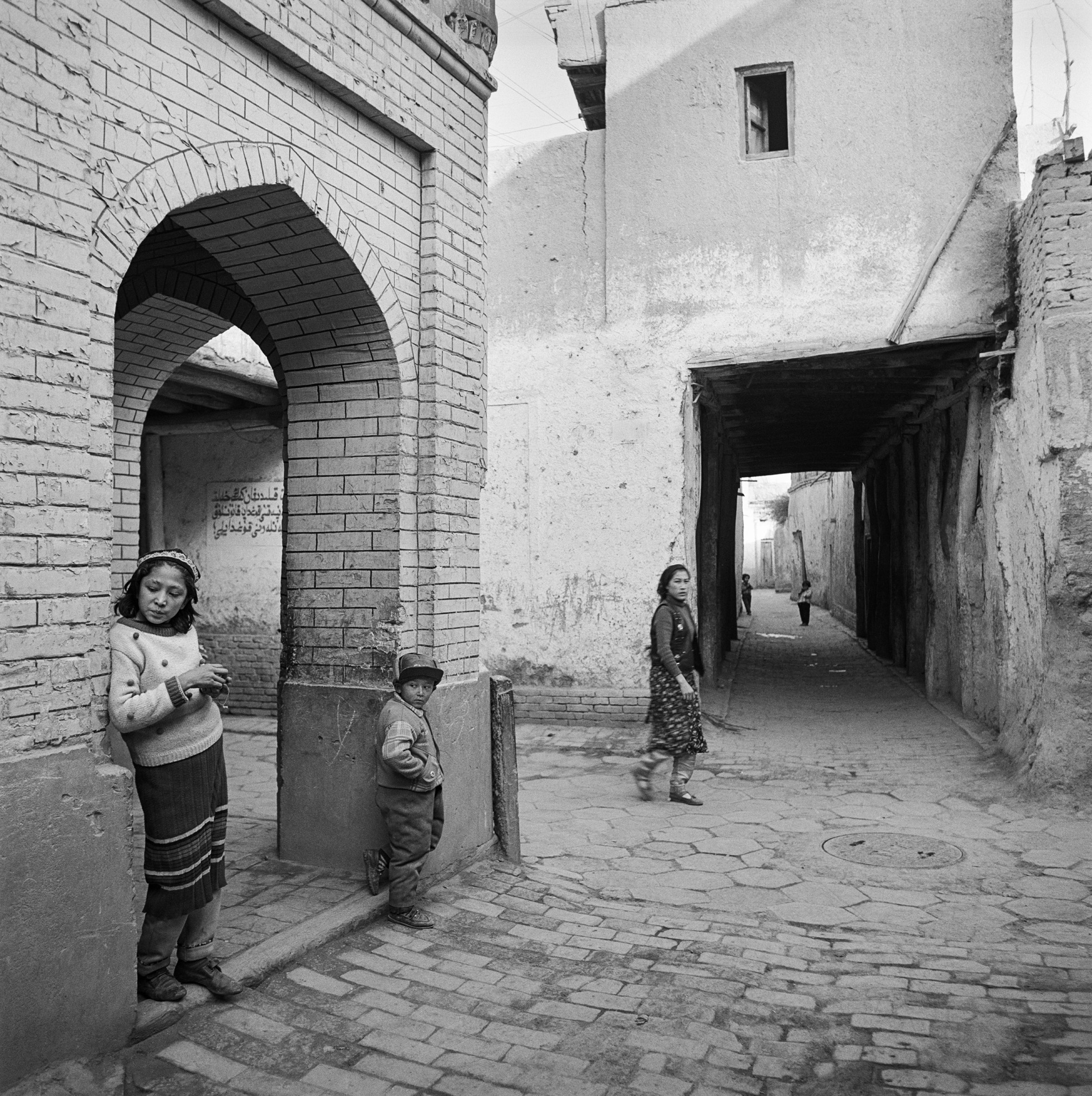

At the Abaq Khoja Mosque. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

Xinjiang has become a vast surveillance state, with Uyghurs constantly under the eye of the police. Their movements are followed, cell phones are searched, and very few are allowed to leave. Having contact with people outside of China, downloading the Quran, or even going to a Mosque to pray can all get a person into serious trouble. Some Uyghurs have been subjected to forced sterilizations, forced labor, and family separations.

At the bird market. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

In 2018, it was estimated that more than 1 million Uyghurs were imprisoned in what the Chinese government referred to as reeducation camps throughout Xinjiang. The camps were established in 2017 and in the years after, despite heavy restrictions, reports began to emerge about what was happening in Xinjiang. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken called China’s radical oppression of the Uyghurs “genocide and crimes against humanity” in 2021. Several countries have also levied sanctions on China because of the treatment of the Uyghur population, rankling the Chinese government, which has denied all accusations.

Uyghur police at the People’s Square. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

Before the rise of Xi, the crackdown, and the camps, American photographer Kevin Bubriski spent time in the city of Kashgar, the ancient capital of the Uyghurs, in 1998.

As Bubriski told me, “I had heard about Kashgar from nonfiction filmmaker and friend Robert Gardner, who went there to scout locations for shooting his first fiction film of J. M. Coetzee’s ‘Waiting for the Barbarians.’ He never went forward with the film but spoke enthusiastically to me about Kashgar and he encouraged me to go. I was fortunate to get a one-week assignment. I stayed on a few more weeks or so and felt excited to be there. I had my two Hasselblad cameras with me all the time and searched for interesting compositions and content.”

Residential neighborhood in the old city before demolition. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

Bubriski was first exposed to photography at the age of 14, when he began developing and printing photographs. He had been influenced by the photographs he saw in LIFE magazine, particularly David Douglas Duncan’s work documenting the Vietnam War, and the photographs in the “Family of Man” book, which was the one photography book in his home growing up.

A boy at the bird market. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

Although 1998 was an uncomfortable time of rapid transformation for the Uyghurs, their cultural heart in the high desert was still vibrant, even as the Chinese government’s brutal crackdown on religion, language, culture, and personal freedom in Xinjiang was about to commence.

“My familiarity with Tibet through numerous visit there in the 1980s and ’90s was important for my understanding of the context of the Uyghurs’ situation politically, economically, and culturally,” Bubriski said. “In 1998 I realized that Tibetans had much of the world’s attention through the voice and presence of the Dalai Lama, whereas the Uyghurs had no such resonant far-reaching voice as the venerated Tibetan Buddhist leader and teacher. I recall feeling that photographs might bring awareness to a larger community of the cultural richness of Kashgar and the threat facing the Uyghur people and their culture. I felt an urgency to be in Kashgar and make the photographs back in 1998.”

Outside the Id-Kah Mosque after Friday morning prayers. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

Bubriski’s photographs capture the Uyghurs’ cultural, economic, familial, religious, and spiritual traditions. The vibrancy, beauty, and grit of Kashgar and its people that Bubriski witnessed and photographed more 25 years ago has irrevocably changed, making his photographs even more significant.

Under Xi, China has embarked on a widespread campaign of destruction, razing mosques, cemeteries, bazaars, and other sites of cultural importance to Uyghurs. Kashgar, long the spiritual heart of the Uyghur culture, has been especially hard hit. Kashgar’s Old City was essentially demolished by 2020, stripped of its authentic cultural elements and replaced with an imagined, tourist-friendly facsimile. Authorities claim the razing was necessary for safety reasons, but in the context of the broader crackdown on Uyghur culture many find that explanation hard to swallow.

School boys and their bicycles. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

“There was palpable tension and unease among the Uyghur community all the time I was there. Two young Uyghur men guided me most of the days I was there, and they were very mindful of how to keep me and my camera out of trouble. My extensive experience in Tibet was good practice for how to be careful in Kashgar. In 1998 there was already new construction of high-rise steel and glass buildings everywhere and within a year the rail line reached Kashgar. There was a feeling among the Uyghurs of the deepening marginalization of their community.”

Residential neighborhood in the old city before demolition. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

In “The Uyghurs: Kashgar before the Catastrophe,” Bubriski’s photographs are accompanied by prose and poetry from Kashgar poet and activist Tahir Hamut Izgil and a historical essay by the late Dru Gladney, both of which add depth and understanding to the Uyghurs’ plight. The texts are presented in both English and Uyghur.

Musical instrument shop and workshop. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

“I felt it was important to have all the text elements of the book translated into the Uyghur language. While there may not be many Uyghurs who can purchase the book, in regions in the world of the Uyghur diaspora, such as Turkey, Kazakhstan, and elsewhere, English is a rarity. I felt it was important to present the Uyghur language as a small part of cultural recognition and preservation.”

At the livestock market, watching while a young man test drives a horse. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

Bubriski hopes that the photographs will give people a glimpse into what Xinjiang, and Kashgar were like, and what the world has lost through China’s policies. What has been erased cannot be replaced, but this important record stands as a testament to Uyghur culture and heritage in their homeland. Bubriski’s book is a stunning work of art and conscience that reveals a time when Kashgar, beloved city of the Uyghurs, retained much of its traditional life and charm.

At the bird market. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

“I hope that through the photographs viewers can get a feeling for the Uyghur way of life in Kashgar before the old city was demolished and before the limitations on cultural and spiritual life were so strict, severe, and dangerous. In Tahir’s and the translators’ essays there is a strong description of the nostalgia that they each feel when viewing the photographs. I would hope that that feeling of nostalgia or loss can be felt by others as well.”

A large statue of Mao overlooking the People’s Square. Kashgar, China, 1998. Photo by Kevin Bubriski.

The Uyghurs: Kashgar before the Catastrophe is published by GFT publishing and can be purchased through their website here.