The relationship between the United States and China, one country an established power, the other a rising power, will decisively shape the 21st century world. Of the many aspects of this relationship, one of the most important is the strategic relationship, with “strategic” meaning the many ways that the two countries’ plans, doctrines, capabilities, postures, and actions interact across the nuclear offensive and defensive, outer space, and cyber realms.

Building a stable and cooperative “win-win” strategic relationship serves the interests of both the United States and China. It would contribute to both countries’ security interests, not least by avoiding dangerous military competition, confrontation, or even conflict between our two countries in the years ahead. A cooperative strategic relationship would also provide a foundation for action to address global political, security, and economic challenges. It would allow scarce leadership attention, political capital, and economic resources in both countries to be used to address pressing domestic, economic, social, and other priorities.

The tough challenges that our countries’ leaders need to address in pursuing greater strategic cooperation are well known. They range from the long-standing political disagreements over Taiwan to mutual uncertainties about each other’s military intentions, plans, programs, and activities – both at the strategic level and in Asia. But there are also important foundations for building greater cooperation, including the economic interdependence between the two countries and the recognition by both countries’ leaderships of the importance of this relationship.

Regarding more specific next steps, five areas stand out for possible future dialogue and action:

First, a top priority in the dialogue process between China and the United States should be to put in place a robust and continuing set of exchanges and other types of official interaction between our two militaries and defense establishments. To the greatest extent possible, such exchanges need to be insulated from the ups and downs of the overall relationship.

Second, a process of mutual strategic reassurance to reduce misunderstandings and lessen mutual uncertainties is needed between our countries. As a start, experts and officials should have a frank discussion of the “why” of mutual reassurance – what issues concern China? What issues concern the United States? Agreement at the official level could next be sought on principles or guidelines to govern a process of US-China mutual strategic reassurance. At the same time, possible confidence-building initiatives for mutual reassurance should be explored at the Track 1.5 and official levels, including strengthened dialogue, joint analysis, table-top exercises, reciprocal visits, and joint military operations. Plus we should not forget that top leaders doing the right thing at the right moment is also a critical part of mutual reassurance.

Third, despite differences between the United States and China on the subject of transparency, the time appears ripe for new efforts in this area. A first step could be a sustained dialogue among experts on each country’s perspectives on the benefits and risks, possibilities and limits of transparency. We still do not understand each other’s thinking on this issue very well. Improved understanding could be followed by an evolutionary approach to greater transparency that would recognize the mutually reinforcing relationship between greater trust and greater transparency. Chinese experts’ suggestions to focus initially on transparency of intentions rather than transparency of capabilities is another building block. We also need to rethink reciprocity, moving from matching reciprocity of one-for-one activities to a new approach. We suggest “asymmetric reciprocity” that would accept possible differences in the amount, type, timing, and detail of information released by China and the United States.

Fourth, traditional treaty-based arms control between the United States and China remains premature. Even so, the two countries could begin a dialogue between their experts on arms control verification technology, practice, and experience as part of their overall commitment to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Again at the expert level, it also may serve both countries’ strategic interests to begin a low-key discussion of the concept of less formal mutual strategic restraint across the offenses-defenses, space, and cyber areas. What would mutual restraint entail, what principles might guide that process, when should it be pursued, and how might each country signal its restraint? Mutual strategic restraint would build on the unilateral restraint that both countries already often show in their strategic postures. The goal would be to lessen mutual uncertainties and build habits of strategic cooperation.

Finally, despite important areas of non-proliferation cooperation, the two countries’ assessments of non-proliferation challenges, as well as their basic approaches to meet those challenges, often differ. More focused dialogue is needed to better understand these differences – and more importantly, to identify areas of complementarily as well as ways to bridge or reduce those differences. Here, both countries have an important stake in enhanced cooperation to strengthen nuclear safety and security in Northeast Asia, as well as globally. Plus, China’s oft-described role as an intermediary between nuclear-weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states (especially in developing countries) could offer opportunities to strengthen global non-proliferation efforts, e.g., in gaining universal adherence to the Additional Protocol, in encouraging implementation of Security Council Resolution 1540, and in achieving success at the upcoming 2015 NPT Review Conference.

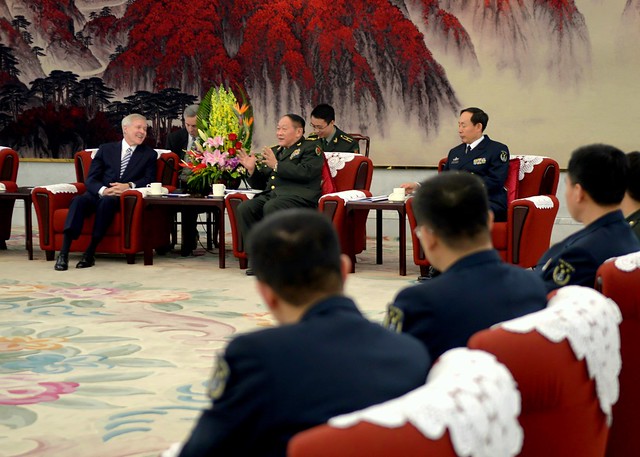

These ideas, among others, are spelled out in a new report – “Building toward a Stable and Cooperative US-China Strategic Relationship” – available in both English and Chinese on the Pacific Forum website . Over the past year, our three organizations cooperated to bring together a small group of American and Chinese experts to carry out a Track 2 joint study of the challenges, but especially the opportunities for building habits of strategic cooperation between China and the United States. Participants included former senior officials, retired military, and think tank experts. In this Joint Study, one American and one Chinese expert each set out his or her thinking on a given aspect of building strategic cooperation, from visions of a long-term goal for the relationship to new options for strategic engagement.

Lewis A. Dunn ([email protected]) is a senior vice president at Science Applications International Corporation, Ralph Cossa ([email protected]) is president of the Pacific Forum CSIS, and Li Hong ([email protected]) is the secretary general of the China Arms Control and Disarmament Association. This article was originally published by Pacific Forum CSIS PacNet here, and represents the views of the respective authors.