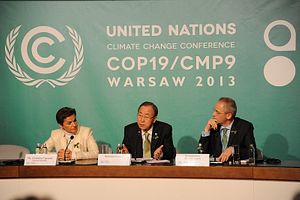

The United Nations Climate Change Conference wrapped up in Warsaw, Poland this weekend. The conference was not expected to produce revolutionary new agreements, but to hold preliminary discussions over a new global climate change treaty that is supposed to be signed in 2015. Even by those modest standards, the conference proved somewhat disappointing. Annie Petsonk, international counsel for the Environmental Defense Fund, told the Washington Post that the talks “are headed toward a C to C-minus for the overall effort.”

Disagreements between the United States and China represent one of the biggest obstacles to a global climate change regime. The conflict was on display in Warsaw. At one point, China, along with the G77 group of developing countries, walked out on the negotiations when developed nations refused to finalize details for a mechanism to reimburse developing nations for climate change damage. The subject of the debate, the Green Climate Fund, would require developed countries to provide $100 billion per year to help poorer countries adapt to climate change. “Funding is the key for the success of the Warsaw conference,” said Xie Zhenhua, head of the Chinese delegation to the UN climate change conference.

This schism is not solely a China-U.S. debate: Brazil, India, and Tanzania, among others, made statements criticizing the developed nations, while Russia, Australia and the EU all argued against developed nations having to foot the bill for global climate change. However, because the U.S. and China often take leadership roles for developed and developing nations respectively, their disagreements are representative of the entire schism. Likewise, if the two countries were able to come to an agreement, it would represent a huge step forward for global climate change negotiations.

China, speaking for itself and on behalf of the developing nations, strongly supports the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” which was originally introduced in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Under this agreement, developed countries, the greatest source of emissions historically, take more responsibility for climate change. In practice, this would mean that developed countries face steeper emission cuts while also helping fund efforts to adapt to and prevent climate change.

China still considers itself a developing nation, citing a low per capita GDP and high poverty rate. However, the climate change debate over common but differentiated responsibilities has been complicated by China’s development. Since the Kyoto Protocol was formed in 1997, China has become the world’s second largest economy and well as the largest emitter of carbon dioxide. Many of the developed nations (especially the U.S.) are simply unwilling to accept a climate change agreement that lists China as a developing nation without regard for its growing share of both the world’s wealth and worldwide emissions.

The United States has always been reluctant to accept drastic emissions cuts. Recently, this foot-dragging has been more and more tied to the United States’ economic rivalry with China — U.S. politicians are unwilling to commit to emissions cuts that would not apply equally to China, fearing that would put the United States at a disadvantage economically.

Meanwhile, China points to per capita emissions, where the U.S. is still the world leader, to argue that the U.S. should make the first move. According to the World Bank, in 2010 China produced 6.2 metric tons of carbon dioxide per capita, compared to 17.6 for the U.S. Based on this data, as well as the idea of historical responsibility, China refuses to accept a climate change regime that forces Beijing and Washington to commit to the same level of emissions reductions. Such an agreement would deprive China’s citizens of the benefits of development already enjoyed by Western nations, Beijing argues.

This creates a vicious cycle, where each country uses the other as an excuse for not acting. Unfortunately, without U.S. and China buy-in, global climate change negotiations cannot move forward. This problem is not new – similar disagreements helped scuttle the 2009 UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen. The failure to reach a binding agreement at Copenhagen was a turning point for U.S. President Barack Obama, who had previously placed a large emphasis on preventing climate change. A personal effort by Obama in Copenhagen was not enough to bridge the gap between the U.S. and China. A few months later, Obama’s proposed cap-and-trade bill died in Congress. Obama’s administration hasn’t really tried to move the issue forward since.

Meanwhile, China has been taking concrete actions on climate change, especially as its historic levels of smog create both domestic and international pressure for action. Just a few days ago, China opened two experimental carbon trading systems in Beijing and Shanghai. China also has other carbon trading systems in the works, with one already open in Shenzhen and others expected to be established in the provinces of Guangdong and Hubei as well as the cities of Tianjian and Chongqing.

Still, most of China’s plans to reduce emissions will only affect the country’s carbon intensity, or carbon emissions as a percent of GDP. Even if China meets it stated goal of reducing carbon intensity by 46 percent between 2005 and 2020, China’s absolute amount of emissions are projected to increase by 73 percent over the same time period. Aware of this fact, China is considering setting absolute emissions targets in its next five-year plan, to be released in late 2015. Jiang Kejun, a fellow at the Energy Research Institute at the National Development and Reform Commission told China Dialogue that “China’s domestic policies are moving quickly, which means we can be more radical in international talks.”

The United States meanwhile is eyeing setting its own emissions targets in early 2015, according to U.S. special envoy for climate change Todd Stern. Despite a general agreement in the scientific community that the problem of climate change demands urgent action, it seems both the U.S. and China are content to play a waiting game, each hoping the other will agree to take action first.