While China’s reemergence is the front-page story of this century, the majority of its Central Asian neighbors are socioeconomically troubled. Undoubtedly developmental challenges have to be met from within, but how important is China to Central Asian stability and economic growth?

Economically, China is already the largest trading partner of four out of the five former Soviet Republics (the exception is Uzbekistan), and a main source of foreign investment. China has increasingly brought landlocked Central Asia into its economic orbit: between 2000 and 2012 bilateral trade (Afghanistan excluded) grew a whopping 46-fold, from about $1 billion to $46 billion. China is also a strategic partner of five of the six Central Asian states, and President Xi Jinping accentuated that status by inking large deals in energy and construction during his visit to the region this September.

All of this is the culmination of China’s diplomacy paradigm in Central Asia, in place since the mid 1990s. The paradigm been characterized by resource extraction and trade; securing land energy supply by importing gas from Turkmenistan and both gas and oil from Kazakhstan; and protecting China’s western territories from possible insurgency spillovers. While currently these threats seem relatively marginal, domestic and regional stability is key to China’s steady progress, an idea frequently expressed in China by the government and scholars.

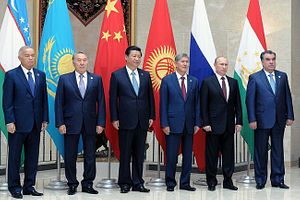

Correspondingly, China has pushed for regional security cooperation under the auspices of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which Beijing founded in 2001. With observer states included, the SCO accounts for half of the world’s population. Even if in different capacities, it is the only security organization in the world to embrace four major civilizations – a historic feat.

Through the SCO political and economic ties have fortified, and member states have developed greater mutual trust in military affairs as cooperation between defense ministries progressively deepens. In practice, so far, this has mainly resulted in collective drug trafficking mitigation, fighting organized crime, and border security enhancement. The SCO still excludes hard security – actual defensive military capacity.

While Beijing primarily sees raising living standards in this region as the antidote for instability, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi has recently stressed that there is opportunity to build the SCO “into a community of interest” by expanding the scope of collaboration and to “build up a security shield” to detect and handle various security threats. Interestingly, this path could deviate from Beijing’s policy of non-interference.

The question is whether current economic engagement and soft security provision can prevent and handle potential mayhem in Central Asia. Challenges and threats confront the region – waiting for havoc to justify hard security capacity building is passive. While Kazakhstan is performing impressively as the product of pragmatic economic governance and an impressive natural resources endowment, other Central Asian states are still struggling in their transition to modernity. Leadership succession is not too far down a bumpy road. The four most troubled Central Asian states – Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan – face grave developmental insecurities: inadequate public services, porous borders, feeble security forces and fledgling economies. Running an indigenous economic growth mechanism in these states without solid foreign partnerships is a major challenge.

At the same time, the regional security climate will change after U.S.-led international forces depart Afghanistan in 2014. Afghanistan’s position at the crossroads of Central and South Asia could possibly see insurgency spillover in vulnerable neighboring countries.

Moreover, Central Asian states feel little allegiance to one another. As rivalries persist, regional institution building from a Eurasian stakeholder would be most welcome. Given its comprehensive resources and economic prowess, China is the most qualified candidate. While Russia obviously has historic, lingual and cultural ties and still considers Central Asia its “sphere of influence,” it is not the resources-hungry manufacturing powerhouse that China is. Emerging India has too many domestic challenges that need to be addressed first, and the EU is mired in introspection.

Understandably, some would state that first and foremost China is responsible for its own developmental challenges. Meeting the needs of its population, one-fifth of all people on earth, is its most important contribution to humanity. Yet while that is irrefutable, instability in Central Asia could stall China’s geostrategic progress in securing land access to the energy riches of the region and the Greater Middle East; jeopardize a shortcut to the Indian Ocean through Pakistan; and threaten Beijing’s ambitions to connect with the major European economies overland.

Moreover, look east and China is surrounded on all sides by states friendly with the United States. Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Myanmar are a few examples of neighbors that find China’s growing influence disconcerting. That underlines the necessity for Beijing of a regional defensive body that embraces China’s west and north.

It would be prudent, then, for Beijing to have the SCO begin a dialogue on clear blueprints for conflict prevention, crisis management, defense cooperation and post-conflict rehabilitation. While this is no easy task given the security calculations of regional powers and the existing overlapping security structures initiated by Moscow, the cost of inaction is higher. The good news is that China and Russia have started to recognize each other as their most important strategic partners in Eurasia, and their relations have never been as sound as they are now. This unique situation affords an excellent opportunity to expedite the common development of SCO members and observers.

Nonetheless, there are a few bottlenecks that need to be addressed first. The first is the name Shanghai Cooperation Organization. No regional security body should bear the name of single country or city – it is simply bad diplomacy.

The second is the delay in granting current observers – particularly Afghanistan, India and Pakistan – member status. Current members could catalyze the political, legal and technical preparation of these nations for SCO membership through stronger support. India’s member status could (or rather should) dampen any concerns Moscow and Delhi have about Beijing’s geopolitical intentions in Central and South Asia. China should also mitigate the hazard that Russia might lean more westward, as advocated by Zbigniew Brzezinski, through fortified security and economic cooperation. This latter is materializing particularly fast; forecasts have Sino-Russian bilateral trade at $200 billion by 2020.

The SCO should also expedite discourse with all Central Asian stakeholders on collective hard-security provision under agreed scenarios of turmoil in the Central Asian states. Defining the threshold for interference is no easy task. To make sure Afghanistan is not forgotten again, an “Afghanistan Mission” under SCO auspices for this economically troubled country could be created once the U.S.-Afghanistan Bilateral Security Agreement is signed – most likely in the next few weeks.

While more opportunities than challenges await the SCO, the suggestions made here will not be easy to achieve. It will be difficult for China not to step on toes, as the weight and interests of all stakeholders need to be incorporated. But if China can indirectly support Central Asia in eliminating the conditions that breed social unrest by improving living standards and molding a more prepared and more muscular SCO, good fortune will have befallen Central Asia – and China.

Richard Ghiasy is a fellow at the Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies (AISS) in Kabul, and a former analyst at the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan to the PRC.