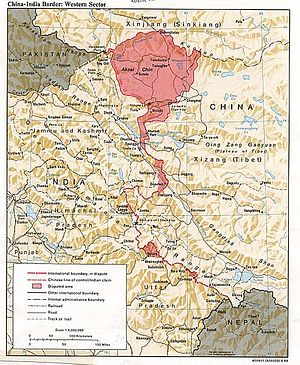

In light of China’s recent decision to cast an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over most of the East China Sea, it’s worth revisiting the recent bilateral agreement between India and China. The so-called Border Defense Cooperation Agreement (BDCA) was signed by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Premier Li Keqiang on October 23 in response to the incursion of Chinese troops into the Indian-controlled region of Kashmir, west of the Line of Actual Control (LoAC) which demarcates Chinese-administered Aksai Chin from Indian-administered Kashmir. China’s ADIZ strategy in the East China Sea might hold important lessons for India in its future border dealings with China; the differences in the two approaches are worth appreciating.

The India-China BDCA can be read as a spectrum of confidence-building measures (CBMs) between the two rivals — it’s an attempt to achieve Li Keqiang’s stated desire for “tranquility” on the border as well as Manmohan Singh’s desire for “predictability.” As my colleague Shannon Tiezzi noted earlier this week, China’s stated objectives in establishing the ADIZ over the East China Sea are to establish a “safety zone.” The similarities between the two approaches end with these rhetorical flourishes.

Many analysts (myself included) found the BDCA to be an underwhelming temporary resolution to the ongoing India-China dispute, but in hindsight, and in light of China’s ADIZ, the BDCA demonstrates China’s willingness to do something with New Delhi that it would likely never be able to consider with Tokyo: communicate, consult, and deliberate. The BDCA established a hotline between New Delhi and Beijing to be used in case of future border incidents. Capital-to-capital hotlines, admittedly, aren’t great at reducing tension. India and Pakistan established an hotline earlier this year to manage border skirmishes and prevent inadvertent escalation, but the rate of border incidents has remained mostly constant.

The key difference between the BDCA and the ADIZ is China’s preference for dialogue in the former and unilateralism in the latter. After the Daulat Beg Oldi/Depsang incident in April 2013, China managed to extract an important concession from the Indian side by effectively managing to freeze Indian military infrastructure on its side of the LoAC — enshrining its own advantage in Aksai Chin, where China has established a more developed military presence. China was willing to engage in dialogue over the BDCA after it already had the upper hand in the matter of the dispute. In the case of the East China Sea, particularly the rigmarole over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islets, China is ostensibly in a far worse position. Japan nationalized the islands, and the Chinese are far less confident about their naval capabilities in the East China Sea vis-a-vis Japan than they are about their capabilities against India.

The BDCA and ADIZ present two different case studies in China’s attempts to alter the status quo on its border disputes with its neighbors. As Zachary Keck noted last week on his blog, the ADIZ demonstrates China’s preference to redefine the status quo via “lawfare.” It’s a bold way of promulgating China’s interests over the East China Sea and the manner in which Japan, South Korea, and the United States have responded attests to this. If PLA rhetoric is to be believed, and the ADIZ was really about building a “safety zone,” the Chinese approach would have been better off modeled on the BDCA approach it took to India. The asymmetry about the East China Sea dispute, however, left this option off the table. Consultations with Japan over the ADIZ couldn’t have gained any momentum precisely due to the lack of China’s ex ante leverage.

I still remain unconvinced that the BDCA wasn’t a missed opportunity, but in light of the ADIZ, it certainly represents the “less bad” option for managing a border dispute with China. This comparative exercise certainly overlooks several important variables such as history. China’s historical posture vis-a-vis India has generally been colored by its victory in the 1962 war and perceptions of a generally advantageous position abound in Beijing on the Aksai Chin dispute (the Arunachal Pradesh case is another story). The same can’t be said for China’s historical perception of Japan, which underlies current nationalist sentiment against Japan and underscores the nature of the current dispute in the East China Sea.