Sunday saw a tearful apology from Song Binbin, a controversial Red Guard figure connected to the brutal death of teacher Bian Zhongyun. The Monday story, which appeared in The Beijing News, opened the old wounds of the Cultural Revolution, and thrust one of the nation’s most tumultuous eras of political turmoil back into the limelight. Despite claims of openness from the powers-that-be, the controversy surrounding Song Binbin is fast being squashed by China’s propaganda authorities.

Since the Cultural Revolution ended, conversation on this period has been whitewashed, muzzled, muted, and censored. According to a memo leaked to the China Digital Times from the State Council Information Office, China’s propaganda overlords, the official gag order on all things Cultural Revolution will continue. The memo, an altogether strange — but by no means uncommon — method of getting the government’s message across, reads: “Because online public sentiment is complicated, all websites must cool down the story ‘Song Renqiong’s Daughter Song Binbin Apologizes.’ First, remove the article from homepages. Interactive platforms must not promote related topics.”

While the CCP and media attempt to portray the Cultural Revolution as a transparent topic, nothing could be further from the truth. True,”scar literature” and books on confessions from that time are commonplace, but having the Cultural Revolution in the news is generally frowned upon. Themes such as Mao’s exact role, the CCP’s responsibility and prosecution are strictly controlled or censored. As such, apologies are generally viewed with suspicion, and the State Council Information Office isn’t the only party directing the conversation.

To help drive the government’s point home, the state-run Global Times waded into those waters this week with an editorial on the subject of the Cultural Revolution, just to make sure people don’t get the wrong idea about Song Binbin’s apology. While the editorial called Song Binbin brave, it also called for introspection rather than apologies: “Disregard the fact that the whole nation has defined the Revolution as what it should be, a handful of people demand the CPC and central government apologize for the Revolution. In fact, the nationwide introspection of the 1980s is more constructive than a so-called apology.” However, the “whole nation” has not defined anything; various groups paint the Cultural Revolution in many lights and are forced to do so with extremely broad strokes.

Two other “small” groups of people were brought to task over the Cultural Revolution in the Global Times’ clarification: “Firstly, a small group of people, who are mostly marginalized by society, start to sing an ode to the Cultural Revolution.” This refers to China’s leftists, a constant thorn in the government’s side. These leftists decry what they call “historical revisionism” of the Cultural Revolution and have been known to target those who apologize for their actions during this time. The size of China’s leftist movement is unknown, but calling them “marginalized by society” is more a vague hope than a census.

Next, right on cue, the editorial took shots at democracy and internet freedom: “Secondly, some malicious actions, such as defaming, rumor-mongering and personal attacks, which were notoriously popular in the period of Cultural Revolution, were brought back to life in the context of the free Internet. Some people are concerned that China might re-walk that disastrous road, while some believe these actions are all for democracy, which can be achieved even at the cost of law and order.”

Binbin apologized with other classmates and described the shame of her role in the Cultural Revolution as “a source of lifelong pain and remorse.” This sentiment is echoed by many who participated in the total madness of the Cultural Revolution, but when the conversation about the Cultural Revolution gets too big, the propaganda department steps in. The official paranoia about the Cultural Revolution is not that far removed from the leftists — the government fears some may try to change the official message of the era. One such leftist, Sima Nan, famed for his outright hatred of the U.S. and difficulty with escalators, said of the recent spate of Cultural Revolution confessions, “I have to speculate that there may be some forces trying to use the second generation of revolutionary families’ apologies to sway public opinion on the Cultural Revolution.”

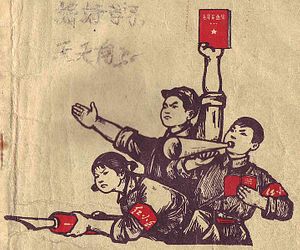

Song Binbin’s apology surprised many. She truly emerged in the public eye at the start of August 1966 (a month now notoriously termed “Red August”) when she was met by Chairman Mao at Tiananmen Square. There, she put a Red Guard armband on the Great Helmsman. This meeting changed her life and even – arguably – her name, which Chairman Mao suggested should be “Yaowu” (meaning “be militant”) rather than “Binbin” (which means “be elegant”). With that, Song became a lightning rod and a propaganda tool for Mao’s war against his political enemies.

But the real controversy surrounding her stems from the death of Bian Zhongyun at the Girls’ Middle School attached to Beijing Normal University, the first murder of the Cultural Revolution. Former classmate Wang Youqin claims Song Binbin was one of the Red Guard leaders, but in a 2003 documentary called Morning Sun, Song insisted, “I never participated in the Red Guard destructions, not even once … I feel so wronged because I was always against physical violence.” At first glance, Song’s apology is no different the hundreds of other confessions from that tumultuous time, but given her status as a Red Guard icon and her father’s position as one of the “Eight Elders” of the CCP, the story quickly gained traction.

As such, Sunday’s tearful confession comes as a bit of a shock, leading many to claim that it was insincere. When questioned on this point by The Beijing News, Song said, “If I wasn’t prepared for that, I would not have stood up to do it.” Confessions from the Cultural Revolution are still a touchy subject and one that is ever under the watchful gaze of the propaganda authorities, who are largely concerned with the current Party’s role and responsibility. This puts the confessors themselves under considerable strain.

The scope of the conversation means a great deal to those who lived through and participated in the Cultural Revolution. In The World of Chinese, in an issue themed around modern communism in China, Ginger Huang’s article “Confession Controversy” discusses the culture of the Cultural Revolution confession and why it’s important. She quotes 55-year-old Wang Keming, who traveled across the country to apologize to the man he hurt in the Cultural Revolution after 34 years of personal emotional torture. Wang said: “Hate possessed us: wherever our eyes landed, we saw enemies. When such a generation is thrown into a turbulent age, they persecute others or become persecuted themselves — or become brainwashed … However, when they are able to look back at history, and denounce the hate education they received, the ‘Party nature’ gives way to human nature.”

Without a free media in China, that look back seems as far away as ever. From the left, confessors are roundly abused and dismissed. To the government, both the persecutors and persecuted are responsible for the deeds the CCP set in motion so long ago. Meanwhile, the media steers the conversation with judicious suspicion. Despite appearances, China is a long way away from open discussion of the Cultural Revolution, and as the generation of the Red Guards ages, a chance to learn is being lost.