Foreign policy, generally, is never a major issue for the Indian electorate ahead of an election, but as the country gets ready to head to the polls to choose its next Prime Minister later this year, the time seems right to reflect on the performance of the incumbent UPA government in foreign policy matters over the past decade.

I’ll start by saying that Indian foreign policy in general is perhaps criticized more than is warranted–India pursues and secures her interests with more foresight than conventionally appreciated. The UPA government’s tenure in New Delhi has been a period of rather momentous geopolitical change in Asia. As the UPA came into power in 2004, geopolitical themes that resonate today–such as the rise of China–were more than palpable. Other themes, such as the United States’ global decline and a broader shift to multipolarity or “G-Zero,” were less so. Regionally, the seemingly perennial issue of Pakistan persisted, but saw no major breakthroughs.

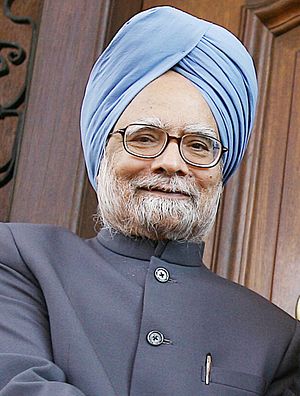

Although the term never really caught on, the notion of a “Manmohan Doctrine” is helpful in understanding what India’s technocratic professor-prime minister had in mind when he rose to the helm in 2004. Often criticized for leading the country despite never having been elected to any office, Manmohan Singh was the man who eased India into the 1990s, managing a disastrous balance of payments crisis as India’s finance minister. His professorial proclivities colored his perceptions of foreign policy. Singh was no realist; as an economist, his “doctrine” was that Indian foreign policy should privilege economic goals as the driver of India’s national interest.

Had pre-2010 economic indicators in India persisted to this day, Singh’s schema for foreign policy would have been undoubtedly a success, but today India laments the loss of double-digit annual GDP growth rates. After the financial crisis in 2008, India’s annual GDP growth stood at 3.9 percent. It peaked in 2010 at 10.5 percent, finally sliding to 3.2 percent in 2012. During that same period, inflation indices climbed–the rupee’s dramatic cliffhanging against the dollar in 2013 highlighted this as well.

The trade story is far more positive for India, though still wanting in certain areas. The most recent success in this area came with the passage of the WTO’s “Bali Package” trade deal–one where Indian negotiators succeeded in pursuing India’s protectionist agenda. The deal satisfies India’s concerns about its domestic food security. The UPA’s tenure over the past 10 years also saw India conclude numerous free trade agreements, including with South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, and ASEAN, with negotiations continuing on many others. While India concluded many agreements and pursued its agenda effectively, it hasn’t managed to close trade deficits with major partners.

India and Pakistan managed to avoid another conventional war in the 10 years that UPA was in charge, but concomitantly stagnated in making any progress on the matter of Kashmir or a broader peace. The progress that Atal Behari Vajpayee forged in the wake of the Kargil War, with his trip to Lahore, and attempts at bilateral engagement did not seem to inspire confidence in the Congress-led government. The 2008 Mumbai attacks and the ensuing evidence that the attackers were backed by the Pakistani military and intelligence establishment dashed any attempts at peace between the two countries as well. As I wrote in my 2013 retrospective on India-Pakistan relations, a series of leadership changes in Pakistan won’t fundamentally alter India’s approach to security in Kashmir and other sensitive matters. The rare meeting between Indian and Pakistani DGMOs at the end of 2013 is also disappointing.

India’s response to the rise of China is naturally a major question in evaluating the past decade in its foreign policy. Despite their major border disputes over Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh, China and India have cooperated on a global level rather successfully. When it comes to issues like climate change and trade talks, Beijing and New Delhi formed a significant portion of a “developing country” bloc and found much commonality in their agendas. Meanwhile, India’s “Look-East” Policy has been put to the test as India bumps shoulders with China in forging diplomatic relationships with ASEAN countries. As my colleague Zachary Keck wrote, India has been playing somewhat of a “double game” in this sense–balancing the pursuit of its national interest and its position vis-a-vis China.

India’s relationship with the United States remains important, but woefully undercapitalized. If I’d written this column in early December, I might have been more sanguine about the progress made in India’s relationship with the United States over the past decade, but as we witness the dénouement of several weeks of diplomatic drama regarding the fate of Devyani Khobragade–an Indian diplomat arrested in New York under suspicion of falsifying documents and mistreating her domestic servant–it is apparent that much of the progress in this important bilateral relationship remains superficial and undercapitalized.

Manmohan Singh, to his credit, will always have the successful civil nuclear cooperation deal with the United States, which was concluded in 2006 and approved by the U.S. House of Representatives in 2008. In an interview just last week, Singh fondly recalled the nuclear deal as the “best moment” of his entire tenure as Prime Minister. The deal eventually opened the door for India’s waiver at the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and carved out a niche for India in the global community as a non-nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT) compliant nuclear power. Other positive indicators that India and the United States converged under the UPA’s watch include the increased frequency of bilateral security consultations, and military exercises (see the Malabar series of maritime interdiction exercises). A burgeoning trilateral security process between the U.S., Japan, and India–the first of which took place at the end of 2011–suggests that India is beginning to link its cooperation with the United States to its cooperation with Japan, a major Asian partner.

Overall, the most reasonable evaluation of India’s foreign policy fortunes under the UPA is that the UPA’s first term in power was significantly better handled than its second. The economic story best affirms this assertion. Under the UPA’s second term, India passed over numerous opportunities to deepen bilateral engagement with the United States after signing the nuclear deal in the first term. India’s misguided legacy of non-alignment seemed to be rearing its head again as it failed to build on important strategic momentum with Washington. It remains to be seen if Washington and New Delhi can put the diplomatic row behind them and focus on their clearly convergent interests in the Asia-Pacific.

Apart from the Khobragade saga and its revelations about the state of the Indo-U.S. relationship, 2013 could leave a sour taste in the UPA government’s mouth as it prepares for an increasingly uncertain electoral outcome. The Depsang incident in April and the Border Defense Cooperation Agreement signed between India and China in October both revealed India’s position vis-a-vis China at the negotiating table. Despite India’s acquisition of mountain divisions and increased defensive capabilities, the UPA’s tenure resulted in no major breakthroughs with China on the Line of Actual Control. India’s regional leadership was tested when Sri Lanka hosted CHOGM 2013–the Prime Minister’s decision to politely decline attendance was a missed opportunity, as I argued then.

Going forward, India’s next government will continue to wrangle with the same sorts of foreign policy challenges as the incumbent UPA coalition. One of the major success stories of the UPA-era has been India’s huge but oft-ignored strategic convergence with Japan, which should have major implications in India’s strategic thinking in the future. Regardless of who wins the next Indian elections, the trajectory set by the incumbent UPA government with China, the United States, Pakistan, and ASEAN will endure.