The Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN) and Japanese Maritime Self Defense Forces (JMSDF) are “destined to cooperate” in an increasingly fluid and competitive security environment in Northeast Asia.

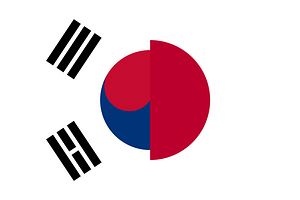

Both the ROK and Japan share bilateral security treaties with the United States, prioritize protection of shared sea lines of communication, and face the challenge of addressing the threat of North Korea’s ballistic missile and nuclear weapons program. Still, these overlapping strategic interests have not translated into substantial bilateral security cooperation. The potential benefits of robust JMSDF-ROKN ties are widely agreed upon among defense officials in Tokyo and Seoul, but lingering historical disputes over Japan’s colonial legacy in Korea, along with a territorial dispute over a set of islets (called “Dokdo” in Korea and “Takeshima” in Japan), impede the development of a close naval partnership that would further anchor peace and stability in Northeast Asia.

While it has been less than two decades since Japan and ROK established formal navy-to-navy ties, Japan’s indispensable role in supporting U.S. operations on the Korean peninsula has been evident for over half-a-century. During the Korean War, then-Rear Admiral Arleigh Burke called upon Japanese minesweepers from the Maritime Safety Agency (MSA) to clear Soviet mines in waters off of Wonsan, which ultimately provided the U.S. Navy access to launch a decisive amphibious assault at Wonsan in October 1950. Japan’s timely provision of minesweeping capabilities was integral for a short-handed U.S. Navy that relied on a handful of wooden auxiliary minesweepers after disbanding Commander Mine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (COMINPAC) in 1947.

More than 60 years later, the importance of Japanese support for U.S. operations around the Korean peninsula remains unchanged. DPRK development of nuclear weapons and ballistic missile technology further raises the potential for a destabilizing contingency on the Korean peninsula, in which case trilateral U.S.-Japan-ROK naval cooperation in areas such as ballistic missile defense (BMD), anti-submarine warfare (ASW), and mine-warfare (MIW) will be critical against asymmetric North Korean capabilities. As retired-JMSDF Vice Admiral Yoji Koda argues, seamless interoperability between the JMSDF and ROKN in ASW and MIW will be necessary for securing the Korea/Tsushima Strait, which in turn, will be “indispensable to the ability of both ROK and American forces to fight and maintain themselves, and to the U.S. alliances with both South Korea and Japan.” Although ROKN modernization over the past 15 years has transformed it into an advanced, ocean-going navy, current ROKN shortfalls in ASW/MCM training and capabilities provide a powerful incentive for the ROK to cooperate with Japan, which can offer Seoul the extensive ASW/MCM experience necessary for protecting U.S. carrier strike groups and amphibious ready groups that are deployed to the Korean peninsula during heightened tensions or wartime.

The potential strategic benefits of JMSDF-ROKN cooperation are not limited to the aforementioned tactical and operational benefits, however. In fact, the political utility of naval cooperation on regional security dynamics, especially as it relates to shaping China’s rise, is an increasingly compelling reason for Japan and the ROK to place historical and territorial disputes on the back-burner and prioritize addressing imminent threats to the regional status quo. For example, in response to China’s demarcation of its air defense identification zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea in November, Seoul and Tokyo decided to conduct a joint search-and-rescue naval exercise with destroyers and helicopters without submitting flight plans to Beijing. This exercise reinforced South Korea and Japan‘s rhetorical rejection of China’s ADIZ.

U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral naval cooperation and exercises would also place greater pressure on China to condemn, rather than defend, DPRK provocations such as the sinking of the ROKS Cheonan and shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in 2010. This view was articulated in a statement released after a series of trilateral track two dialogues among representatives from the U.S., Japan, and the ROK, where participants agreed that China’s military modernization and reluctance to censure DPRK for these two incidents required U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral collaboration to “prevent China from engaging in such [assertive] behavior.”

The U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral relationship will be ever-more salient as the U.S. addresses regional strategic challenges such as North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and China’s anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities. Bolstering naval cooperation beyond joint-BMD and humanitarian aid exercises will ultimately require Seoul and Tokyo to move past disputes over history and territory that have recently plagued their relationship. North Korea will not wait for Japan and the ROK to mend ties before staging its next provocation. The strategic imperatives, opportunities, and benefits of Japan-ROK naval cooperation are significant, and the time to expand this relationship is now.

Samuel Mun currently works at the Project 2049 Institute, where an earlier version of this article first appeared.