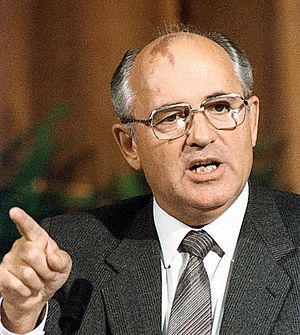

The host invited me to talk about today China’s political situation. But to talk about this, I would want to complain and to criticize, and I long ago made a rule: not to criticize China overseas. If I’m going to criticize China, I will return to China first and then proceed. So today, I can only talk about Gorbachev, a foreign retired leader, more than 80 years old. Talking about him is very safe.

From the common people to the leaders, China’s “Gorbachev complex” is very serious. There are people who hope that China will soon have its own Gorbachev, and there are also people who are trying their hardest to avoid the emergence of a Chinese Gorbachev. For those who want a Chinese Gorbachev, it’s because he was committed to reform, almost single-handedly ended the Cold War, toppled the powerful but fairly sinister Soviet empire, and brought democracy to Russia and other countries. Others hate Gorbachev because his reforms failed. Not only did he cause the downfall of the ruling Communist Party, he also made a superpower crumble overnight. Plus, the democratic transitions in the ensuring 20 years have not been smooth.

Were Gorbachev’s reforms wrong? Could his failure have been avoided? If Gorbachev’s reforms had succeeded, what would the result have been? Everyone knows my assessment of Gorbachev, but today I’d like to proceed from a different angle and do some more objective analysis, to better understand the Soviet Union. It’s also additional food for thought for China.

The Soviet system is not unfamiliar to us. After Gorbachev came to power, the system was already coming close to the “seventy years limit” I’ve spoken of before: it was corrupt and difficult to operate. Its collapse was imminent. Gorbachev followed the historical tide—he put forward the “new thinking” and implemented reform, trying to save the party and the state. Even those people who fume about Gorbachev don’t dare to attack the content of Gorbachev’s reforms. The reason is very simple: how can it be wrong to make the government transparent, destroy totalitarianism, return power to the people, realize democracy, and give people more freedom? No one would be stupid enough to radically criticize the content of Gorbachev’s reforms. Otherwise, even before criticizing Gorbachev, the critic would show himself to be rotten.

Reform was necessary. Without reform, the state dies, so reform! But Gorbachev’s reform failed, and his failure caused the ruling party to lose power and led to the collapse of a vast empire. Many people say that the reason for his failure was that the Soviet Union was terminally ill—reform and improvement could not save it. The only options were revolution or waiting for it to die a natural death. The only thing you could do is hope that your own health is good enough so that you could survive a bit longer than the state. There’s some truth to this. For systems like the Soviet Union’s, there was no precedent for successful reform. Gorbachev’s efforts were like walking forward in total darkness, refusing to accept failure until he was forced to. But this argument still does not deter our pursuit for the other reasons Gorbachev’s reforms failed.

In hindsight, let’s imagine if Gorbachev’s reform had stuck to “eating the meat” without “biting into the bones.” What if his reform had been small-scale, with lots of noise but little results? Or what if he had tried “crossing the river by feeling the stones” in the economic sphere, gradually relaxing the rigid, planned economy’s control over the public and no longer preventing people’s desire to get rich? In that case, his reform could not have been successful. It also wouldn’t have caused many problems and, what’s more, couldn’t have really failed. Perhaps the Soviet system could have continued for several years or even decades. Gorbachev would have been the envy of his successors, a Soviet version of Deng Xiaoping. But the moment Gorbachev came to power, he went straight to “biting into the bones”: tackling the difficult reforms of the political system and of society.

Ordinarily, this is right. The problem was that Gorbachev thought he had a lot of authority. He was very confident about the Soviet system, his “new thinking” theory and his chosen road for reform. Without having gained absolute control of the army, police power, and the authority to reform, he immediately started talking the most difficult reforms. And what was the result?

During that short period, when Gorbachev spoke of democracy, Yeltsin was more democratic than him in almost every way. When Gorbachev spoke of adhering to the leadership of the party, party conservatives were more Communist than him in almost every way. He took the lead in loosening control of the media, but the media were not willing to let him off the hook. Almost as soon as the reform began, Gorbachev lost control of it. In less than a few years, he had made enemies of forces inside and outside the system, as well as both the left and the right. To the extreme conservatives, he was seen a as “traitor to socialism,” while at the same time the extreme liberals labeled him a “traitor to democracy and freedom.” Gorbachev’s situation back then was a bit like mine on the internet today: looked down on by both the left and the right.

So, was it possible for Gorbachev’s reform to succeed? Not only Gorbachev himself, but also his successors believed this was possible. In fact, at the beginning Gorbachev’s reform, both in its direction and its specific content, actually received support from the enlightened group within the system, from the liberal intellectuals, and from most of the people. If Gorbachev had had more clear goals and a “top-down design” rather than taking a “crossing the river by feeling the stones” mentality into the deep waters of reform; if he had grasped the party, the government, and especially the military and police (KGB) power firmly in his own hands rather than having elder party members dividing his power and challenging his authority; if he had from start to finish placed reform under the leadership of the party rather than listening to the attacks of either conservative or liberal forces—then, from both a tactical and a technical level, the probability of success would have been great.

But there is a problem: in accordance with the Soviet system (and we Chinese are very familiar with, aren’t we?), if you want to place reform under the absolute control of Gorbachev, he would need to follow the same practices he is resolved to get rid of. He needed to make a severe extralegal attack on autocracy and corruption within the system—this way he could have avoided the coup that had him imprisoned for three days. He needed to fight a merciless battle against Yeltsin and the rest of the democracy advocates within the party, shutting them up or even putting them under house arrest—this way he could have avoided these figures always taking the high ground during the democratic reform process, having the authorities shoulder responsibility for the “original sin,” and having Gorbachev himself passively suffer scoldings from every direction. Gorbachev needed to triumph over the extreme conservatives and at the same time use more extreme measures to deal with the liberals and the media—this way he could have avoided not having any way to handle them after opening up (instead, in the end, the media almost all rose up to “handle” Gorbachev).

But all these steps and measures mean running in the opposite direction of the goal Gorbachev pursued! When Gorbachev tried to make his end and his means consistent, he was quickly eaten up by his own reforms. As the saying goes, “the revolution devours its children.”

Even more interesting—this Gorbachev, who was eaten by his reforms, actually cemented his historical legacy by failing. To be clearer: Gorbachev’s failure was his biggest success.

Personal success does not necessarily indicate the people’s success; personal failure sometimes actually means historic victory. It’s rare to have failure cement someone’s status as a “great man” in history. Gorbachev is one of these cases. But for a long time, Gorbachev himself did not agree with this type of “greatness.” After stepping down, Gorbachev traveled to the West to give speeches. When people regard him as a hero who overthrew the Soviet Union, he repeatedly said, “If party conservatives and radicals like Yeltsin had not ruined it, my reform would have succeeded, and the Soviet Union wouldn’t have fallen.” Gorbachev’s meaning is clear: if his reform had succeeded, the Soviet Union would have eventually moved toward freedom, democracy and the rule of law, but without Yeltsin’s ten years of chaos (including the economic crisis) and without Putin using an immature democratic system and electorate to create a “dictatorship.” The Soviet Union would not have disintegrated into more than a dozen countries.

In the last few years, there have been an immense number of books about the disintegration of the Soviet Union and Gorbachev, but almost nobody has the imagination envision such an outcome: if Gorbachev had succeeded in his reforms, what would the result be? A prosperous, strong, democratic, free Soviet Union as socialist superpower? Or would it only mean Gorbachev’s personal victory—with Gorbachev still serving as the Soviet Union’s chairman and general secretary, becoming, at over 80 years old, one of the world’s longest serving dictators (dwarfing Suharto, Mubarak and Gaddafi)?

Gorbachev has left us a textbook full of experiences and lessons. Reform is necessary, there’s no doubt. Few people challenge that the goal and the direction of reform should conform to historical trends, and even the manner, methods and procedures of reform are not an issue. The question is whether or not the leader implementing reform has the authority and power to see the reforms through. After an authoritative leader obtains power, he won’t necessarily reform (for example, leaders such as North Korea’s Kim dynasty, Egypt’s Mubarak and Libya’s Gaddafi). An authoritative leader who is willing to reform may not reform all the way (such as Deng Xiaoping). But a leader who wants to thoroughly reform must hold absolute authority in order to be successful (for example, Taiwan’s Chiang Ching-kuo).

Those who deny the direction and content of Gorbachev’s reform must know that going against the tide of history can only delay the inevitable for a short while. If anti-human systems don’t reform, in the end, the leaders and the system will be swept together into the dustbin of history. You have great power, but this only means having the power to bring yourself historical shame. Today, China in many respects has already surpassed the reforms Gorbachev pushed forward in the Soviet Union.

At the same time, those who hope for a Chinese Gorbachev should realize no leader in the world is willing to be eaten by his own reforms. In China, aren’t there even fewer leaders in the reform school who are willing to be destroyed by the reforms they began and promoted?

The historical choices are not many. How can we choose the path of Gorbachev’s reform, but without repeating his mistakes? How can we be a successful Gorbachev—neither the Gorbachev whose reforms failed, nor the Gorbachev who is thought successful because his reforms failed, but a Gorbachev whose reforms succeed? Obviously, this requires not only political ideals, but also political authority, political wisdom, and political skill.

At a time when the Russians have gradually forgotten Gorbachev, and Western enthusiasm for him has died, China’s “Gorbachev complex” is still going strong. History cannot be predicted. The Soviet Union’s reform has already ended, but China’s reform is not only not finished, but new reforms are just getting started. China, with a system similar to the Soviet Union’s, is still walking alone on the path towards the future. China needs a reforming Gorbachev, but this Gorbachev definitely won’t hope for his own reforms to fail.

I’m talking about the Soviet Union and Gorbachev, and taking the 83-year old Gorbachev as my target—this must really disappoint those friends who wanted to hear me throw out incisive opinions on China’s political situation. Please allow me to make a joke: if I were Gorbachev, what would I do? I guess I would have no choice. I would follow the historical tides, and make a top-down plan to lead the Soviet Union towards freedom, democracy, the rule of law, and prosperity. I would seize control of the military police and the national security apparatus, secure the power to initiate reforms, defeat the extreme forces on both the left and the right, and then implement reform measures step by step…

Unfortunately, I’m not Gorbachev, and even though I’m forcing myself to imagine Gorbachevs, I actually don’t have much confidence in the system he represents. So I tend to agree that Gorbachev’s great success lies in his failure. I hope that in the future Gorbachev can succeed, and transform his success into the success of the people, the country, and the nation.

This piece originally appeared in Chinese on Yang Hengjun’s blog. The original post can be found here.

Yang Hengjun is a Chinese independent scholar, novelist, and blogger. He once worked in the Chinese Foreign Ministry and as a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington, DC. Yang received his Ph.D. from the University of Technology, Sydney in Australia. His Chinese language blog is featured on major Chinese current affairs and international relations portals and his pieces receive millions of hits each day. Yang’s blog can be accessed at www.yanghengjun.com