On Thursday a senior Indian official appeared to endorse Russia’s position in Ukraine in recent days, even as Delhi urged all parties involved to seek a peaceful resolution to the diplomatic crisis.

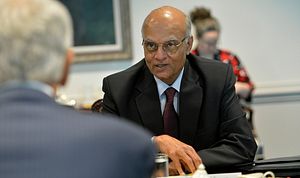

When asked for India’s official assessment of the events in Ukraine, National Security Adviser Shivshankar Menon responded:

“We hope that whatever internal issues there are within Ukraine are settled peacefully, and the broader issues of reconciling various interests involved, and there are legitimate Russian and other interests involved…. We hope those are discussed, negotiated and that there is a satisfactory resolution to them.”

The statement was made on the same day that Crimea’s parliament voted to hold a referendum for secession from Ukraine.

Local Indian media noted that Menon’s statement about Russia’s legitimate interests in Ukraine made it the first major nation to publicly lean toward Russia. As my colleague Shannon has reported throughout the week, many of China’s public statements could be interpreted as backing Russia in Ukraine, despite Beijing’s own concerns about ethnic breakaway states and its principle of non-interference.

However, at other times, including at the UN Security Council, Beijing has appeared to be subtly rebuking Moscow by suggesting that its unilateral path threatened regional and global stability. At the very least, however, Beijing has characteristically not gone as far as the U.S. and the West in publicly scolding Vladimir Putin for the military intervention in Crimea.

Ukraine certainly appeared to interpret India’s endorsement of Russia’s legitimate interests as far more hostile than Beijing’s position on Russia’s actions. According to the Telegraph India, a Ukrainian embassy spokesperson stationed in Delhi responded to Menon’s comments by saying: “We are not sure how Russia can be seen having legitimate interests in the territory of another country. In our view, and in the view of much of the international community, this is a direct act of aggression and we cannot accept any justification for it.”

The larger question, of course, is why India decided to take such a relatively pro-Russian stance on the Ukraine issue? There are a number of possibilities.

First, India and Russia have long-standing ties and Moscow is Delhi’s top arms provider. Moreover, Russia and the former Soviet Union has been nearly alone in the international community in continue to back India during crucial moments such as following its 1974 and 1998 nuclear tests.

It’s also possible that Delhi believes Russia’s intervention offers the best chance of stabilizing Ukraine. India’s Foreign Ministry on Thursday also released a statement noting that there are “more than 5,000 Indian nationals, including about 4,000 students, in different parts of Ukraine.” At the same time, India’s overall interest in Ukraine is fairly negligible—certainly less than China’s, for instance—and thus Delhi might assess that it has more to gain by publicly sticking by Moscow at a time when it desperately needs support.

India also has plenty of interests in certain regions along its peripheral, and at certain times—such as during the Sri Lanka Civil War—has intervened to protect various societal groups with strong ties to India. Unlike China, then, India may assess it has an interest in an international precedent in which major powers can intervene in countries along their borders. At the same time, such an international precedent could be used by Pakistan to justify intervening in Kashmir.

Telegraph India offers another reason. According to the report cited above, Indian officials have told Telegraph India that, in the newspaper’s words, Delhi is “convinced that the West’s tacit support for a series of attempted coups against democratically elected governments — in Egypt, Thailand and now Ukraine — has only weakened democratic roots in these countries.”

This rationale would be consistent with India’s long-standing, deep-seated abhorrence to anything that merely resembles Western imperialism. At the same time, India has not historically made supporting democracy abroad a central tenet of its foreign policy.