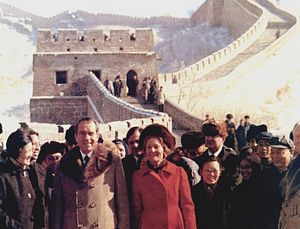

When President Richard Nixon’s National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, flew to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1971, two decades stretched between his rapprochement efforts and U.S. de-recognition of the PRC. While there will be those who declare comparisons between this period and current P5+1 talks with Iran untenable, significant similarities do exist, from both countries’ geopolitical importance to the fervor of anti-rapprochement detractors. Iran, with its tenuous balance between moderates and religious hardliners, even recalls China of the early 1970s when internal, even murderous, power struggles erupted over U.S. overtures and sparked close brushes with the Americans. Given these similarities, it is worth studying early Sino-American rapprochement efforts and applying its lessons to current talks with Iran.

At the beginning of his historic week in China, Nixon expressed hopes that the talks would begin a process for problem-solving. “And the way to do it […]” he argued, “is to lay the problems on the table, talk about them frankly and with good temper, and find the areas where we can agree and where we cannot agree.” This ability to exchange ideas and opinions about the world at the very top eventually became a point of pride between the two former adversaries. As Kissinger and his successor, Cyrus R. Vance, met with Chinese officials, Ambassador Huang Chen, Chief of the PRC Liaison Office, proudly noted that Kissinger had made nine trips to China since 1971, during five of which he spoke directly with Chairman Mao Zedong. These talks provided insights into Chinese foreign policy thinking and decision-making in ways that secondhand snippets of conversations and diligent summations of People’s Daily editorials could not.

Following this tradition, P5+1 leaders should engage President Hassan Rouhani in honest, informal talks in addition to the more formal negotiations. After decades of embittered isolation, the U.S. knows little about Iran or its worldview. Where formal relations do not exist, states must often parse rhetoric, gestures, and inadequate intelligence for meaning, leaving room for misinterpretation and missed messages. Confused and inconclusive U.S. National Intelligence Estimate reports on Iran’s nuclear capabilities more than underscore this dearth of knowledge, and perspectives gained from open discussions can only clarify the path ahead.

Despite the expansive nature of such open talks, in the case of the U.S. and China, both sides maintained disciplined focus on the key roadblock to normalized relations—Taiwan. In some ways, the Chinese rendered this discipline mandatory, evincing lukewarm to no interest in agreements on arms control, trade, and exchanges (scientific, cultural or otherwise). China’s lead negotiator, Prime Minister Chou En-lai, further structured negotiations to emphasize the singularity of the Taiwan issue. Presented with Kissinger’s seven-point discussion plan (with number seven being an open-ended invitation), Chou engaged Kissinger in negotiations over Taiwan but merely offered Chinese viewpoints on the others. When Kissinger sought to link Taiwan with other issues, including forces in Indochina, he was systematically and repeatedly rebuffed.

Chou’s focus was useful in that agreement between rivals is a process, not a magic trick. This is more so the case when active antagonism characterizes decades of severed relations. In the aftermath of World War II, China opposed the United States in the Korean and Vietnam wars, providing funding, arms, and even manpower. The United States, for its part, committed to the defense of Taiwan seemingly overnight and successfully sought the removal of the PRC from key multilaterals. Against this background of bitterness and mistrust, Taiwan then stood as the preliminary test of good faith for the Chinese, a litmus test on which future cooperation and progress could be built. Similarly, after years of being vilified and isolated, Iran deserves talks designed to overcome the past and to set in motion a long-term process of cooperation, an objective that the February’s concern over ballistic missiles does little to further.

What finally emerged from these Sino-American conversations was a vague formulation in the Shanghai Communiqué and a more concrete but secret five-point agreement on Taiwan, with full implementation of the agreement expected after Nixon’s reelection. Though Nixon’s second term domestic troubles would prevent the realization of this promise, the United States made significant concessions in these five-points, secretly promising an evolution towards a One China and assuring Chinese leaders that Nixon could do more than he could say publicly. The Chinese, for their part, agreed to be flexible with timing, dropping clear deadlines for troop withdrawals from Taiwan and postponing a final resolution of the Taiwan issue. Speaking to Nixon, Chou stated, “We have already waited over twenty years—I am very frank here—and can wait a few more years.”

Flexibility, though not the “Nixinger”-level secrecy, should carry over into current talks with Iran. Ending decades-long enmity and disagreement does not realistically occur without some flexibility, and both sides will need gains to showcase and to quell domestic and international detractors. It would be a mistake, however, to equate such flexibility with weakness or with an invitation for the other side to overstep its bounds. Early Sino-American talks did not unfold in a vacuum, and even as its leaders conceded where they could, the United States carefully calibrated and maintained its overseas military presence to signal its intolerance for recklessness and adventurism.

Ultimately, not everything from the Nixinger period merits mimicking, particularly its excessively secretive and unilateral nature, and there will be other, major considerations determining the outcome of the P5+1 talks. To read the history of Sino-American rapprochement and normalization is to trace the lifespan of the Cold War, the American electoral cycle, and the rise and fall of a sitting president’s, or chairman’s, political capital. This is to say that progress and hopes for a thaw in U.S.-Iran relations today will rest on the realities of the broader regional and international scenes, the domestic usefulness of rapprochement to both countries, and the rare alignment of political will and capital.

Cynthia Lee worked as a research assistant to China scholars at Columbia University and NYU, with a focus on archival research. Prior to that, she provided research support for the Asia Society’s participation in Track II dialogues with Iran.