Public memory in India when it comes to the country’s dealings with great powers is long. The past often rankles. The disastrous 1962 India-China war is one example; Richard Nixon’s 1971 attempt at gunboat diplomacy with India is another. The latter story is familiar to all interested in how the Cold War played out globally, the gist being this: In December 1971, a U.S. carrier strike group led by the USS Enterprise entered the Bay of Bengal as a warning to India, as India and Pakistan fought a war that led to the creation of a new nation, Bangladesh.

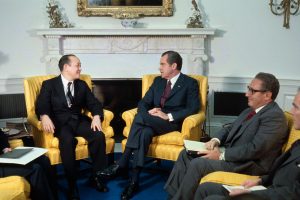

On the surface, this was a typical Cold War play as Nixon’s National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger saw it: Pakistan was a treaty ally of the U.S. and was the staging ground for Kissinger’s outreach to China. India, on the other hand, had entered into a “Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation” with the Soviet Union a few months before, in August. Kissinger worried that India was aiming to decimate Pakistan militarily, opening greater space in the region for the Soviets. Sufficiently spooked by the possibility, he also encouraged the People’s Republic of China – and this was before Nixon’s landmark 1972 visit – to open a front against India. Despite repeated warnings from the U.S. consul general in Dhaka, Archer Blood, that the Pakistan army was engaged in despicable atrocities inside its own country – albeit in the eastern, Bengali-speaking half – the Nixon administration continued to think of the crisis there in terms that look dreadfully simplistic in hindsight, not to mention completely off.

The USS Enterprise came and went, China never joined the war, and by December 16, Pakistan’s military had surrendered to India’s – seriously bruised but far from being completely decimated.

The political authority behind India’s decision to go to war in 1971 was Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, a fiercely combative personality whom Nixon disliked from the get-go. But what is striking about Nixon’s attitude toward Gandhi is its misogynistic, racist framing, which went far beyond the rational. Transcripts of conversations between Nixon and Kissinger, which are being declassified in bunches, are in parts unprintable both due to the coarseness of language as well as the profanity of thought.

In a new essay published in the New York Times on September 3, the historian Gary J. Bass (who chronicled the U.S. diplomacy around the birth of Bangladesh in a 2013 book) revisits this deeply disturbing attitude of the duo toward Gandhi, by examining a recent tranche of declassified Nixon-Kissinger conversations. By looking at a past instance of racism and misogyny at the highest levels of the U.S. government, Bass wants us to probe the present. In at least once instance, current President Donald Trump has mocked Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s accent, a small episode in a long history of racism.

But beyond the issue of straight-up irrational prejudice, Bass’ essay raises three subtle questions. To what extent can consideration of race or culture or religious beliefs be legitimately (by the standards of the time) considered inputs in foreign policy decisions? To what extent have these considerations overridden all others and, having done so, been masked in the language of power and interest? And, finally, should genuine (by standards of community) intellectual effort – and the policy prescriptions that follow from it – be discarded solely because it aligns with malign beliefs?

Consider Samuel Huntington’s clash of civilizations thesis, first published as a Foreign Affairs article and then expanded into a 1997 book. In Huntington’s analysis (simplified to an extent), the international system was set to fragment along religious-cultural-civilizational lines; from this, conflicts would inevitably follow. As scores of academics have since argued, Huntington’s book – which got massive play in certain circles following 9/11 – suffers from a host of methodological and other issues. But to imagine that Huntington, one of the world’s most renowned international relations theorists, would have purposefully written a racist screed is out of the question.

Now take the same thesis in the hands of former policymaker Kiron Skinner, an African American scholar of considerable repute. Skinner, as then head of the U.S. State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, last year had framed the U.S.-China strategic rivalry in terms of a clash of Western and Chinese civilizations. Most damagingly to Skinner’s reputation, she noted, “I think it’s also striking that it’s the first time that we will have a great power competitor [China] that is not Caucasian.” At that time, commentators had taken Skinner’s remarks as further evidence of the Trump administration’s racism – “the real Trump Doctrine.”

And yet, the Trump administration had prided itself on its “principled realism,” asserting that great power competition is the key challenge ahead. Another academic and (briefly) Trump administration official, Nadia Schadlow – who was instrumental in drafting the 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy – has coherently described it as “conservative realism.”

Have Skinner and Schadlow simply veiled Trump’s racism in palatable terms, framing prejudice as an issue of national interest? Or is it simply the case that parts of his administration’s brain trust use unfashionable (and perhaps, intellectually problematic) policy frameworks? These are not easy questions to answer, not the least because Trump is who he is.

Perhaps 50 years from now, we may see some newly declassified documents that shed light on the question. For now, the fact that it must be asked is troubling enough.