U.S.-China relations are at a crossroads. China, now the number two economy in the world (and, depending on who you ask, projected to pass the U.S. as number one in 2016, 2020, 2028, or not at all), has a growing political and military clout commensurate with its economic prowess. Accordingly, China has a strategy for achieving a long-time goal: gaining control of its near seas, at least out to the so-called “first island chain.” The U.S., for its part, is loathe to cede its role as the dominant power in the Asia-Pacific, especially given its alliance relationships with many of China’s close neighbors (including South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, and, unofficially of course, Taiwan).

But the issue of military or diplomatic dominance in the Asia-Pacific is merely a microcosm of the greater challenge: finding a balance of power between the U.S. and China that is acceptable to both nations. Many analysts have framed this dilemma as the “Thucydidean trap” that arises each time a rising power challenges as established one. To try and escape this historical trap (which has generally led to war), China’s leaders have proposed that China and the U.S. seek a “new type of great power relationship.” But what does this actually mean?

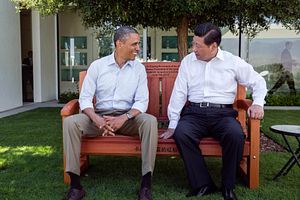

At one meeting between the U.S. and Chinese presidents, there were plenty of ideas on how the U.S. and China could work together. According to the American president, “China and the United States share a profound interest in a stable, prosperous, open Asia” so cooperation on the issue of North Korea’s nuclear program is a must. There’s also a need “to strengthen contacts between our militaries, including through a maritime agreement, to decrease the chances of miscalculation and increase America’s ties to a new generation of China’s military leaders.”

On a global front, “the United States and China share a strong interest in stopping the spread of weapons of mass destruction and other sophisticated weaponry in unstable regions and rogue states, notably Iran.” In addition, there is “the special responsibility our nations bear, as the top two emitters of greenhouse gases, to lead in finding a global solution to the global problem of climate change.”

And the Chinese president offers a broader assessment of what U.S.-China relations should look like: “It is imperative to handle China-U.S. relations and properly address our differences in accordance with the principles of mutual respect, noninterference in each other’s internal affairs, equality, and mutual benefit.”

The above are solid (if vague) proposals that offer a blueprint for moving U.S.-China relations forward. But hold on—those quotes weren’t from President Barack Obama and President Xi Jinping. The speakers were President Bill Clinton and President Jiang Zemin during a press conference in 1997. 17 years later, in 2014, these same issues are still being hashed over and trotted out as areas for improvement. Despite a mind-boggling proliferation in high-level meetings, Beijing and Washington have made little progress on the very issues they’ve been highlighting as areas of cooperation for nearly 20 years. Outside of a steady increase in bilateral trade, have U.S.-China relations really progressed since the 1990s? And if not, how can Beijing and Washington be expected to draw closer now, when the competition between the two is even greater?

Forget the “Thucydidean trap”—China and the U.S. are caught in the foreign policy version of the “prisoners’ dilemma.” Both understand, on a theoretical level, that the best outcome can only be reached via cooperation. But neither country trusts the other to cooperate (for reasons outlined in detail in a report by Brookings’ Kenneth Lieberthal and Peking University’s Wang Jisi). Both sides can “win” through cooperation, but since neither Beijing nor Washington really believes that will happen, they both seek not to be the country left holding the bag when the other side inevitably turns hostile.

There are real reasons for mutual distrust between the U.S. and China—they have competing visions for both the Asia-Pacific region and the international governance structure. In a nutshell, the U.S. is content with the status quo (where America is the widely acknowledged leader of both), while China is not. Beijing wants to take over the leadership role in the Asia-Pacific and have more of a role in global rule-setting, both of which China believes are necessary to complete the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

Both Chinese and American leaders have acknowledged that a stable (or at least peaceful) U.S.-China relationship is crucial to the welfare of both peoples, and to the world as a whole. But as China’s status as a world power moves from the hypothetical to the real, so will the “Thucydidean trap”—meaning both counties will need to figure out new ways to engage each other that take into account the real dangers of uncontrolled competition. The U.S. in particular needs a new framework for China policy that accounts for China’s increased global stature as well as its global ambitions. Interacting using a paradigm developed in the 1990s won’t cut it anymore.