You’d think that with the news coming out of Tokyo since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took office that Japan is inexorably headed down a path to normalization. Famously, the country is forever banned from practicing offensive warfare by Article 9 of its post-war constitution. In addition to this, Japan has had self-enforced bans on collective self-defense, weapons exports, and nuclear weapons that have all been challenged to varying degrees in recent years. As a democracy, however, Japanese civil society is still happy to push for the nation’s peaceful post-war heritage. One group, in particular, has been campaigning the Executive Committee for the Nobel Peace Prize in Norway to grant the prestigious award “to the Japanese people, who have abided by Article 9 [of the Japanese constitution] and have not waged war in nearly 70 years.”

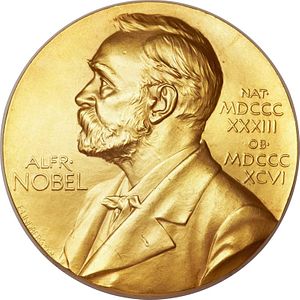

The campaign may seem rather odd. Naomi Takasu, the 37 year old homemaker leading the charge, was initially denied a nomination by the Norwegians because the peace prize cannot be awarded to constitutions — only people or organizations. She then changed her nomination from Article 9 itself to the Japanese people. However outlandish the campaign may seem, a potential Nobel Peace Prize for the Japanese people for having abided by Article 9 of their constitution would send a powerful symbolic message. The Nobel Peace Prize is regularly used as a political tool by the Norwegian Committee to highlight important global issues, placing the onus on the recipient to behave in a certain manner. With prizes in recent years going to an American president one year into his term and the European Union, the committee has certainly indicated its willingness to apply its symbolic moral leverage to world affairs.

The European Union example is particularly applicable. The prize was delivered at a time when Euroskepticism was burgeoning across the continent following the financial malaise of the European “south.” The prize was a reminder that the European Union as an institution had solved the seemingly intractable post-Westphalian problem of perpetual warfare between sovereign states in Europe. Similarly, as debates rage today in China and South Korea that Japan is “re-militarizing,” a symbolic recognition of Article 9 could go a long way to preventing Japan from heading down a more nationalistic path that could be regionally destabilizing.

What would the ramifications of a Nobel Peace Prize going to Article 9 of the Japanese constitution be? Well, on the one hand, it may help assuage the aloofness of Japanese politicians to the manner in which Japan is perceived abroad (something that Robert Dujarric pointed out recently here at The Diplomat). Takasu notes that if Japan did receive the prize, she would want its nationalist Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to receive the award on the country’s behalf. Further, given East Asia’s fixation on Japan’s negative history, including the atrocities of the Imperial Japanese Army, the prize would send a message that it is better to focus on the present (a pacifist Japan) than the past. This certainly wouldn’t be a panacea for the ongoing historical disputes that have increasingly plagued East Asian international relations, but it could help.

To be entirely realistic, the prospect of Article 9 of the Japanese constitution winning the Nobel Peace Prize is remote, but it is certainly entertaining to consider the effects of such a symbolic gesture on Japan’s position in the region. China, I should note, has its own Confucius Peace Prize which was set up, in part, to oppose the Western values of the Norwegian committee (one Confucius Peace Prize recipient just annexed a chunk of Ukraine for example). Perhaps China should consider granting the Confucius Peace Prize to Article 9 of the Japanese constitution if the Norwegians aren’t up to the task.