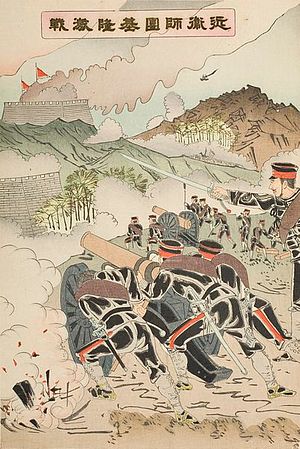

China is gearing up for the 120th anniversary of the First Sino-Japanese War, which began in 1894 and ended with China’s defeat in 1895. The war was a devastating blow to China’s then-rulers, the Qing dynasty, as China had always considered Japan a ‘little brother’ rather than a serious competitor. The war is often seen as the defining point when power in East Asia shifted from China to Japan, as Tokyo claimed control of the Chinese territories of Taiwan and the Liaodong Peninsula (site of the port city of Dalian) as well as Korea (which changed from being a Chinese vassal to an officially independent state under Japanese influence).

To commemorate the 120th anniversary of the war, Xinhua published a special supplement to its Reference News newspaper. The supplement consisted of 30 articles by members of the People’s Liberation Army “analyzing what China can learn from its defeat” in the Sino-Japanese war. Summing up the articles, Xinhua said that “the roots of China’s defeat lay not on military reasons, but the outdated and corrupt state system, as well as the ignorance of maritime strategy.” This conclusion has obvious modern-day applications, as China’s leadership is currently emphasizing both reform and a new focus on China’s navy.

The PLA authors laid the bulk of the blame for China’s defeat on the Qing dynasty’s failure to effectively modernize. “Japan’s victory proved that its westernization drive, the Meiji Restoration, was the right path, despite its militarist tendency,” Xinhua summarized. Political commissar of China’s National Defense University Liu Yazhou compared Japan’s reforms to China’s: “One made reforms from its mind, while another only made changes on the surface.”

Though these comments are referencing a conflict from 120 years ago, it’s easy to see the relevance for today. Xi Jinping is trying to spearhead China’s most ambitious reform package since the days of Deng Xiaoping, including not only difficult economic rebalancing but also an overhaul of the way China’s bureaucracy (both civilian and military) is organized. In other words, China still needs to finish the modernization project that the Qing half-heartedly began in the 19th century. Westernization (what today China would call modernization) remains “the right path.”

Other PLA officers argued that corruption was a major contributing factor to China’s defeat by the Japanese in 1895. Vice Admiral Ding Yiping, a deputy commander in the PLAN, blamed the defeat on “corruption and fatuity in politics.” Major-General Jin Yinan, a strategist at NDU, said that China’s Beiyang Fleet at the time had all the necessary equipment, but that the period of peace before the war led to “the general mood of the fleet becoming depraved.”

As part of these reforms, Xi has repeatedly warned about the danger of corruption, particularly in the military. In one of his first major policy pronouncement after being named Secretary General of the Communist Party, Xi urged China’s military to be ready for battle. “It is the top priority for the military to be able to fight and win battles and it is fundamental that the military consolidates itself through governing the troops lawfully and austerely,” Xi said in a speech in Guangzhou. One could say that Xi saw a “depraved” mood in China’s own military, where personal profit concerns outweighed national security. It’s no coincidence that a PLA general now highlights that same factor as a major cause in one of China’s most stinging military defeats.

PLA officers also emphasized the importance of maritime strategy in Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese war. Under this argument, China was defeated because it had neglected naval warfare in its preparations. Up until recently, this remained largely true. China’s naval forces were historically subordinate to the ground forces, as evidenced by the very name: People’s Liberation Army Navy.

However, Xi Jinping has been pushing for more attention to go to China’s navy, as well as its coast guard. In support of this position, Vice Admiral Ding wrote that maritime strategy was a key to China’s defeat 120 years ago, and that the ocean remains central to national interests today. “State security cannot be ensured if maritime rights cannot be safeguarded,” Ding said.

Xi Jinping apparently shares this view, as he has called for China to become a maritime power. “The oceans and seas have an increasingly important strategic status concerning global competition in the spheres of politics, economic development, military, and technology,” Xi said at a July 2013 study session with Politburo members. China’s new focus on naval assets has also brought renewed attempts to demonstrate sovereignty in disputed maritime areas from the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands to the Spratlys. The Xinhua articles use the Sino-Japanese War as a lesson to back Xi’s increased focus on maritime security and strategy.

Last, but certainly not least, the PLA experts ended with the most obvious argument: that the First Sino-Japanese War proves the dangers of militarism in Japan. Chinese officials generally use Japan’s World War II conduct to criticize modern-day Tokyo, probably because this gives their criticisms a global application. But to China, the First Sino-Japanese War actually marked the beginning of Japan’s militaristic, imperialistic tendencies. Chinese scholars see this trend as continuing unabated until Japan’s defeat in World War II—which is also known as the Second Sino-Japanese War in Chinese (or, more colloquially, as the War of Resistance Against Japan).

Several of the PLA authors drew explicit parallels between the lead-up to the Sino-Japanese War and today. One national security policy expert, Peng Guangqian, said that the rise of militarism in Japan today echoes the situation in Japan in 1894. He warned China to “guard against the sneak attacks that Japan has a history of making.”

However, unwilling to end on a sour note, Xinhua ended by citing General Liu’s argument that, despite losing the war, China ‘won’ in the long-term. Liu said that China’s memory of the “humiliation” of its defeat helped spark its current rise to power, whereas Japan is still suffering the consequences of its overreach in World War II.

Foreign scholars are more interested in looking back at World War I and its implication for Asia, but in China they have their sights set even farther in the past. Chinese military officers are using the memory of one of China’s most humiliating defeats to argue for the importance of modern-day issues like reform, a naval build-up, and the need to be wary of Japan. The implication is clear: follow Xi’s prescriptions, or risk another national humiliation.