62-year old Xiang Nanfu was detained earlier this week for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” He picked these quarrels and provoked this trouble by posting stories to Boxun, a blocked Chinese language website that relies on citizen journalism and which should be taken with a giant grain of salt on all occasions. Journalists are disappearing around China as the dreaded June 4 anniversary approaches, and Beijing wants writers to know that they’re not safe, regardless of where they publish.

The naming and shaming of Xiang Nanfu has been particularly harsh, with a quick televised confession up as early as Tuesday on CCTV. Complete with green prison vest, Xiang confessed to being part of the well-known Western-led global conspiracy to tarnish China’s image in the eyes of right-minded Chinese people — who can’t view the Boxun website anyway — all for the money. He also had to confess to having sex with other petitioners and having visited “prostitutes several times with other people.” This was added to the state media playing up his “lack of education” and previous criminal record, which Boxun editor Watson Meng claims occurred during the Cultural Revolution.

Shan Renping — now known as the alias of powerful, ultranationalist, pro-censorship Global Times editor Hu Xijin — said of Xiang’s arrest: “Due to the West’s declining financial capacity, the competition among anti-China groups and websites for Western funding grows increasingly intense. Websites like Boxun keep lowering their political bottom line. The quality of the content on these websites also becomes increasingly poor.” Nevertheless, Boxun published news, true or not, that the Global Times would never, ever report.

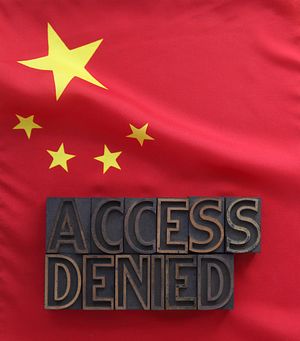

Still, isn’t it a bit rich for the Chinese government to target someone who posts on websites that are blocked for Chinese citizens, a website that, by all rights, shouldn’t even be viewable for China’s constituents? Well, no; like most rule of law in the modern Middle Kingdom, enforcement is highly dependent on the government’s bottom line. In this case, it is adding to the list of journalists arrested in the run up to Tiananmen square, a list that now includes Gao Yu.

The 70-year old Gao Yu was arrested in late April and was charged (illicitly) last week for the now infamous leak of Document No. 9 last year in August. Document No. 9 outlined Xi Jinping’s government’s strategy to attack and suppress Western democratic ideals to protect the party’s rule. Gao Yu’s arrest is largely seen as an attack on Tiananmen remembrance. Considering she spent over a year in prison after the protests, Gao Yu is unlikely to forget them. AP quoted Willy Lam, an expert on Chinese politics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, as calling these arrests an “intimidation tactic.” If that’s so, it’s extremely effective. Gao was sentenced to six years for the same crime back in 1993, and state secrets in China are much like the “provoking troubles” crime: vague and all purpose. Journalists who mistake the freedom of the internet, like Xiang, or press, like Gao Yu, outside of China for sanctuary can expect little asylum.

Everyone climbs the great firewall, and everyone knows that everyone does. That self-same editor that wrote the anti-Xiang editorial above has an account on Twitter — a blocked website that has been blamed for the Xinjiang riots of 2009. Even People’s Daily has a Twitter account, which it used to great hilarity to attack the satirical @RelevantOrgans late last month. Frankly, it would be impossible to navigate the Internet without flouting China’s censorship laws, so Chinese journalists can expect no respite from the Chinese authorities just because they’ve unofficially outlawed certain sites online.

In a very small way, China’s arrest of Chinese journalists who publish overseas like Xiang is an admission of failure to control content, despite some of the strictest Internet sanctions in the solar system. Indeed, if Xiang is guilty of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” surely he is only guilty of doing so in the countries that allow Boxun to be viewed (i.e. pretty much every country except China). Arrests of journalists and human rights activists connected to Tiananmen continue to mount, earlier today claiming the niece of human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang. Beijing is making sure that if you live in China, no matter where you publish, Beijing’s anxieties, insecurities, and gag orders still apply.