As Akhilesh Pillalamarri reports on The Pulse, India, Japan, and the United States are set to begin the latest iteration of the Malabar series of naval exercises. The event is notable for involving three of the most capable navies from democratic countries that operate in the broader Asia-Pacific region. The exercise is a source of anxiety for China as it’s a stark reminder of what Asian waters could look like should its rivals work together to contain it. In 2007 and 2009, China protested Japan’s participation in what was originally envisaged as a bilateral exercise between the United States and India. For India, Malabar represents a step in the right direction. Despite its improving relations with China on the economic front, it is important for India to invest in the future of Asia’s maritime security order.

The Malabar exercise itself is not concerned with broad strategic cooperation, but merely tactical issues, including improving the interoperability of the participating navies in disaster relief, anti-piracy, humanitarian and other missions. However, India rarely participates in these sorts of multilateral exercises in any serious way. Malabar has generally been an exception to this rule. Furthermore, that India took the initiative this year in inviting Japan represents a step in the right direction. Indian naval analyst Uday Bhaskar notes that New Delhi’s initiative is “a reflection of the new strategic environment where there is a degree of unease in India and elsewhere over Chinese activities.”

Similarly, as China has ramped up its assertive behavior in the East and South China Seas since 2012, these sorts of multilateral exercises are a good reminder of the Asian powers that will stand in the way of Chinese attempts to unilaterally revise the status quo. The countries participating in Malabar might allege that the intention is not to contain China, but in reality, the fact that the exercise comprises three powerful Asian democracies vested in the survival of the status quo in the Asia-Pacific is no coincidence.

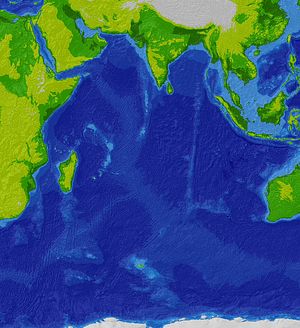

Outside of Malabar, India ought to take up the banner of leading multilateral exercises in the Indian Ocean, its own strategic backyard. As Asia’s second largest country, India could take the lead in hosting an Indian Ocean exercise in the vein of the United States’ RIMPAC exercise which takes place biannually in the Pacific Ocean. In February of this year, the Chinese Navy, ostensibly in an attempt to demonstrate its reach to Australia and India, conducted an exercise in the eastern Indian Ocean. If done right, India’s leadership in the Indian Ocean need not be threatening to China. China will likely treat its maritime interests in the East and South China Seas with higher priority.

This year’s Malabar exercise is an important reminder that India is seeking to “shape the environment by building collective capability,” as Bhaskar notes. Indian foreign policy’s legacy of non-alignment continues to have lingering effects today on the country’s willingness to assertively band together with other nations. With a combination of deft bilateralism and proactive multilateralism, however, India can emerge as the sort of guardian of regional security it deserves to be.