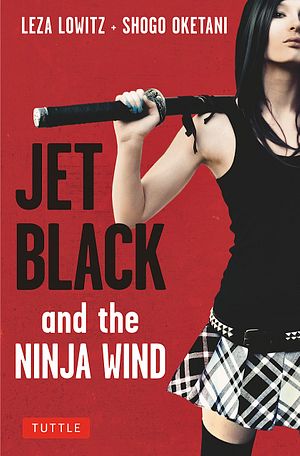

If you need a martial arts fix this summer, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles redux – which has garnered lackluster reviews – is thankfully not the only option. For a refreshing spin on the genre, try Jet Black and the Ninja Wind instead. This young adult novel delivers action, but also digs deeper.

“Most people think of ninja as B-Grade assassins, but there was more to them than meets the eye,” Jet Black co-author Leza Lowitz, an editor and co-translator of contemporary Japanese women’s poetry and pacifist poetry, told The Diplomat. “Why did they develop their arts in secret? Who were they, really?”

In an attempt to answer such questions, Lowitz and her husband and co-author Shogo Oketani, author of J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965, conceived of a trilogy that overturns many assumptions. From challenging the view that ninjutsu is a man’s game – the lead character is a teenage girl – to calling into question the official version of Japan’s history, while drawing parallels to the history of Native Americans, Jet Black is clearly not your average ninja tale.

“We wanted to offer readers another version of history – perhaps a truer version – when it comes to the ninja,” Lowitz continued. “This is not the textbook version, because the textbooks offer the victor’s version of history. Yet, Jet Black is based on ancient Japanese history. This history is little known. We wanted to make it known.”

According to Leza, the ragtag cast of characters includes Jet – a half-Japanese, half-American ninja – her hunter/ninja grandfather, a Navajo Code Talker, a Buddhist priest, and Hiro, Jet’s 12-year-old whiz kid cousin. “Then we have shamans, archeologists, mercenaries, the legend of King Solomon, a ninja dog and a panther,” she said. “How are these diverse elements linked across time and history? The reader uncovers the buried connections as Jet’s adventure unfolds.”

Jet (real name: Rika Kuroi) is a teenage girl who doesn’t realize at first that she is the last surviving kunoichi (female ninja) in a long line of strong female warriors. According to Lowitz, the inspiration to create Jet resulted from frustration.

“I just got tired of reading about Japanese women in kimono shuffling 10 feet behind their men, and seeing this representation on the big screen, too,” she said. “I knew there were powerful Japanese women out there, but we were not seeing them. I wanted to create a strong multicultural Asian female heroine for young girls and boys to relate to. All we had was Tokyo Rose and Mata Hari. Bleh. So Jet was born.”

This story begins with the Spartan lifestyle foisted on Jet by her Japanese mother Satoko who raises her on a Navajo reservation in New Mexico. Although Jet longs to live like a normal teenage girl, her mother knows there are much bigger things in store for her daughter, whom she mercilessly trains in the art of ninjutsu. However, when Satoko dies tragically Jet is left with only a few fleeting details of the elusive Kuroi family history.

With no living family to speak of in New Mexico, Jet boards a plane to Japan and heads north to the mountain village of Kanabe where she is acquainted with the Japanese side of her family. Jet is soon swept into a much larger drama. She is forced to defend her ancestral homeland – centered on the magical Mt. Osore (Osore-zan) where spirits are believed to gather – and to uncover the secrets of her family’s mysterious treasure from a shady group that will do anything necessary to get their hands on the prize.

Crisscrossing the Pacific, the story unfolds within a richly imagined world, from the forested mountains of northern Japan and the concrete jungle of Tokyo to the New Mexican desert and San Franciscan streets. In the process, it links seemingly unconnected worlds and tribes, tapping a more universal vein along the way. Perhaps the story’s most intriguing link can is found between a distinct group who once lived in northern Japan known as the Emishi and the Navajo people of the American Southwest.

In more recent history, Navajo servicemen were drafted during WWII to create a nearly unbreakable code language, which helped lead to Japan’s defeat. Navajo Code Talkers Day was recognized yesterday – August 14 – in the U.S. in honor of this substantial contribution to the victory of the Allied forces in WWII. In an ingenious plot twist, a former Navajo Code Talker is worked into the plot of Jet Black. Saying more would constitute a spoiler, but it’s worth noting that the story draws a compelling parallel between the original inhabitants of the Japanese islands and Native Americans.

But the parallels between Native Americans and Japan’s indigenous tribes run deeper. Beyond drawing on the code talkers and the relatively recent past, Jet Black also draws a spiritual parallel between these groups, both of whom were forced from their homelands. The book also makes an interesting case for the idea that ninja could very well have emerged as a means of survival.

Oketani explains:

Before the Imperial family appeared, there was a kingdom of indigenous people, the Emishi. The Emperor called them “Tsuchi Gumo” – ground spiders. Fighting between the Emishi and the Imperial Army took place through the seventh century, with the last battle at the end of the eighth century. The discovery of gold mines in northern Japan was the reason. The battle ended in victory for the Emperor. Many Emishi were captured and brought to Kyoto slaves. The government made promises that were broken, and the Emishi were betrayed. The Emishi history is much like the history of the Native Americans.

In the Heian era (784 – 1185 A.D.), samurai were warriors under the employ of the aristocracies. They were authorized and employed by the Emperor. The general, or Shogun, was the boss of the Samurai. The Genji and Heike were the main Samurai clans. To be a samurai, one had to be blood relation to a Genji or Heike family.

After power shifted from the aristocratic class to the Samurai class in the twelfth century, unauthorized groups of fighters appeared. These warriors used to be farmers, lumberjacks, hunters, fishermen, or transporters with horses or boats. They became freelance soldiers hired by and supporting the samurai class. They were called Ji-samurai or Akuto. Ji-samurai means “field samurai.” Akuto means “gang.” Some were bandits.

Three big Ji-samurai families lived in Iga province. They were the Fujibayashi family, the Hattori family, and the Momochi family. The people of Iga were independent and didn’t want to be under the control of the Shogun or any authority. But neighboring Koga was a famous ninja village that had a strong relationship with the samurai. Oda Nobunaga, the strongest samurai lord of the sixteenth century, was suspicious of Iga’s independence. His forces attacked Iga three times, destroying the village. Many ninja were killed. The remaining ninja escaped. One was Hattori Hanzo, a famous ninja who served Tokugawa Ieyasu, the First Shogun of Edo. (The subway Hanzomon line is named after Edo castle’s gate (mon) which Hanzo and his soldiers guarded. )

In Jet Black and the Ninja Wind, we imagined that the ninja came from the indigenous people of northern Japan, basing this on actual battles between the native Emishi and the Imperial army in the ninth century. The Emishi were vastly outmatched in manpower and weaponry, and when the Emperor’s army won, many Emishi were brought to West Japan as slaves. Ancient documents say that the Emishi were good at hunting, horseback riding, and were skilled fighters. The Ji-samurai bought the Emishi as soldiers. It is not a stretch to imagine that those soldiers were ninja.”

If this idea sounds far-fetched, it pales in comparison to some of the other historical claims that have been put forward regarding Japan, some of which are alluded to in Jet Black. While the book does not present them as fact, it does offer them up as some fun speculation. Such theories include the idea that Jesus was buried in Northern Japan and the claim that treasures which can be traced back to Israel’s King Solomon wound up on the islands. Some have even claimed that a lost Israelite tribe wandered to Japan where they buried the Ark on Mt. Tsurugi. Jet Black also riffs on the fact that there are numerous uncanny similarities between many Japanese rituals and those found in Judaism.

Regardless of the veracity of these claims, they were not arbitrarily included in the story. “Shogo is a history and culture buff,” Lowitz said. Before working them into the plot, “he knew about parallels between Japanese and Jewish rituals, culture and language. He researched over 50 books in Japanese and English to develop the complicated adventure story.”

Achieving this mix of complex, fast-paced narrative and deep background is where Jet Black excels and no doubt helped it win the 2014 Asian Pacific American Librarians Association (APALA) Award in Young Adult Literature. While the book technically falls within the young adult genre, it offers a wealth of insight that can appeal to more mature readers, as it elucidates Japan’s secret history, carries a strong “eco warrior” undercurrent, and promotes a healthy reverence for strong female characters. It also contains an extensive glossary of ninja terms with entries on background information, as well as a generous dose of Japanese language sprinkled throughout.

These themes and this level of depth and detail will continue in the second and third volumes of the series, due to be published in 2016 and 2017, respectively. Lowitz says a fight against big business, protecting ancient sacred lands, eco activism and political intrigue will come in heavy doses in these forthcoming books.

On balance, the pervading tone of the trilogy feels rather subversive. And this is just fine with Lowitz:

“All the books in the trilogy are based on real events and true history that the government might not want us to know,” she says. “It is our hope that this series reveals the true, ‘inconvenient’ history of our countries [Japan and the U.S.] and what happened to the indigenous people to the next generation so that it is not buried, whitewashed, or forgotten as we go into the future.”