Last week, Alex Ward discussed the potential for a great power war between the United States and China. He framed his argument in terms of prominent international relations scholar Robert Gilpin’s “three preconditions,” as presented in his book War and Change in World Politics. Ward convincingly demonstrates that each of Gilpin’s preconditions is either close to being met in today’s world or has already been met, making the probably of a great power war between the U.S. and China, if not high, certainly non-zero. Ward notes that ” Gilpin’s framework serves as a good rubric by which to measure the current global climate,” noting further that “by all measures, this is certainly a dangerous time.”

Gilpin’s War and Change in World Politics is certainly an important work on state-centric realism, but it might be somewhat more useful to consider the work as a whole rather than just focusing on Gilpin’s three preconditions. While Gilpin does lay out the preconditions for war in chapter five, he frames his argument in the book more in terms of traditional economic theory, particularly expected utility theory.

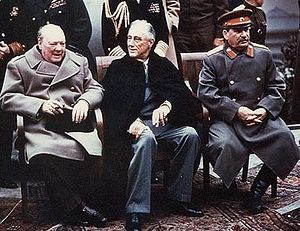

Gilpin’s goal in the work is to explain why the global system sometime changes, often through the means of war between great powers. At the core of Gilpin’s argument is the idea of an existing international equilibrium. This equilibrium reflects the current distribution of power and interests in the global system and is achieved when no state can gain from changing the system (at least will gain less than it would cost that state to bring about the desired change). Empirically, our current global system largely reflects the interests of the allied powers that emerged victorious following the Second World War: the United States and Europe (largely Western Europe). In “equilibrium,” we have a rules-based liberal order that manifests itself via institutions such as the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization.

After establishing the existence of equilibrium as the first hypothesis in this inquiry, Gilpin then argues that change occurs — effectively organically and spontaneously — in the international system. This change has two primary points of origin: it can be a change in the distribution of power internationally or it can be a change in the national interest of a state within that system. This change often leads to a state of disequilibrium where states begin to pull away from the existing order toward a new equilibrium. In Gilpin’s argument, war is a popular way for states seeking a new equilibrium to attain it. He’d probably disagree with Edwin Starr that war is good for “absolutely nothing” — per Gilpin, it’s good for attaining a new international equilibrium.

What is crucial in Gilpin’s argument for states to go to war or for disequilibrium to emerge in the first place is not only a discordance between the global power distribution and the international system, but also a compelling utilitarian reason for states to desire change. Essentially, in the context of the United States and China, the United States would need to decide that its hegemony is too costly for it to continue — the benefits of stepping back outweigh the costs of continuing to lead. On the flip side, China would have to come to the conclusion that disrupting the global order (ostensibly through a war with the United States) is more beneficial than the cost of continuing to abide by it.

Empirically, I see little evidence of either power coming to the above conclusions. For the United States, the benefits of global leadership seem to continuously outweigh the costs of free-riding allies and having to act as the global policeman. Even within the highly polarized world of U.S. domestic politics, most experts continue to favor a broad and forward U.S. role abroad.

With China — and where I think Gilpin’s book is less useful in explaining a possible U.S.-China war — we see even less evidence of a utilitarian motive for war. Despite China’s rapid military modernization, assertiveness in the South and East China Seas, including establishing an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) and “salami-slicing” away territory from other states, and proposals for a uniquely Asian regional security order, Beijing does not have the appetite for the costs associated with a great power war. In convincing ourselves that it does, we may be missing the forest for the trees. The “forest” here is that China’s communist elites value the survival of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and its primacy over the mainland more than they do anything else. All of Beijing’s more assertive behavior is attributable to an extent to the party’s desire to pitch itself as the defender of China’s national interests. Even Beijing’s rhetorical focus since Mao’s day on standing up after a “century of humiliation” speaks to the CPC’s desire to be seen as the legitimate guardian of China. All of this further ignores the immense economic benefits Beijing reaps from its privileged position in the existing global economic order.

As long as the Chinese political elite have to worry about their own survival, they will focus on challenging the United States on narrow issues as they have been doing in recent years. Returning to Gilpin, there is little reason that China would ever assess the benefits of revising the global order as outweighing the costs of doing so anytime soon. The possibility of an all-out great power war remains remote given the current distribution of power and preferences between the U.S. and China. If a war were to occur involving these two actors, it would likely be instigated by a Chinese conflict with a third party and the United States would be drawn in through treaty obligations.

All this said, Ward’s analysis focused on Gilpin’s three preconditions isn’t wrong. In fact, his primary policy recommendation for the United States — “[ensuring] that China is a responsible partner in the current global system alongside it” — squares neatly with the broader themes that Gilpin lays out in his work. In general, however, focusing on Gilpin’s preconditions without considering how they fit in with a state’s rational calculus before deciding to go to war only reveals part of the picture. Thus, while the U.S. and China will continue to have their differences, Beijing will remain content to let Washington have the global lead for some time to come.