In my last piece, I argued that China should send troops to fight the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) for global public goods and its own national interests. I listed five major benefits of doing so. Unsurprisingly, many have pointed out the potential dangers and pitfalls of my proposal, and some of them have good points. After considering all the major counterarguments, I remain convinced that China still should send troops to fight ISIS. Let’s consider these counterarguments one by one.

The biggest worry and concern from many Chinese observers is that the U.S. offer to China is simply a trap to get China involved in a big mess in Iraq. According to this argument, China should not fight the war for the United States. This kind of conspiracy theory is always popular in some quarters in China. The interesting thing is that we cannot tell whether the conspiracy on the part of the U.S. is real or not, but it does not really matter. Whether China will be trapped in Iraq or not depends on China’s own strategic goals and actions. The reason the U.S. was trapped in Iraq for many years was because it had unrealistic and overly ambitious goals, i.e., reforming the whole Middle East through military occupation. China should not and will not pursue such goals as its objectives are much narrower like peacebuilding, peacekeeping, and protecting its own interests.

One related worry is that China’s involvement in Iraq might generate anti-China feelings among terrorist groups and some Arab countries. This shouldn’t be a concern either because, unlike the U.S., China’s goals will be limited. The U.S. went into Iraq for the purpose of regime change, which always generates hatred and resentment. Terrorist groups and some countries in the Middle East hate the U.S. mainly because it has a tendency to impose its own values and systems on others through military occupation and it maintains a special relationship with Israel, which is the root cause of the Palestinian problem. China does not face any of the above issues, thus making itself an unlikely target of Arab anger. In addition, ISIS is also regarded by Arab countries as a cancer to regional stability and peace, further increasing China’s legitimacy in the fight against ISIS. If some groups in the Middle East shift their resentment to China, then it only shows that those groups are already hostile toward China. The best response to such hostilities, then, is to confront them rather than running away from them.

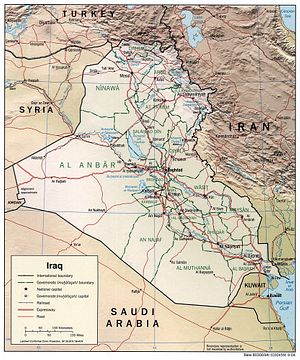

Another concern is that China’s PLA has very limited capabilities to fight overseas. This is true, but it is precisely because of this shortcoming that it is imperative for China to join the campaign against ISIS. By doing so, China can improve its fighting capabilities. Given China’s deteriorating security environment, a military conflict with others cannot be entirely ruled out. In order to win a war, there is no better preparation than participating in a real war. More importantly, a military presence in Iraq could provide solid security for Chinese investment there. Imagine how China’s investment could have been saved during the Libyan civil war if Chinese troops were there. China lost about $20 billion in Libya and its stake in Iraq is much bigger (although most of China’s investments are in southern Iraq, far away from ISIS-controlled territory). Given the uncertainties in Iraq, we can never be sure that our investments are safe. Sooner or later China will need a security force in Iraq and now is a good time to start it. In the next five to 10 years there will be no better opportunity.

In the end, a Chinese military presence in Iraq (if China does send troops there) should meet three preconditions. First, it must be under a U.N. framework. Second, it must focus on humanitarian and peacekeeping purposes and not involve the toppling of a regime. Third, the size of China’s troop commitment must be small, letting regional actors and the U.S. do most of the heavy lifting. If the U.S. cannot agree to these terms, then China should not dispatch a singer soldier to Iraq.