The recent violence along the Line of Control (LoC) between India and Pakistan in Kashmir threatens confrontation yet again between the two nuclear armed neighbors. It also underscores the need to rescue the fragile Track II process from irrelevance, because ultimately it is through genuine people-to-people exchange that long-term peace between the two nations is possible.

While visiting the other country and forging relationships is a gargantuan task for the average Indian and Pakistani, given the nature of the visa regimes on both sides, there are a few groups of individuals who manage to cross the borders quite frequently: select businessmen, members of civil society, academics, and other privileged individuals.

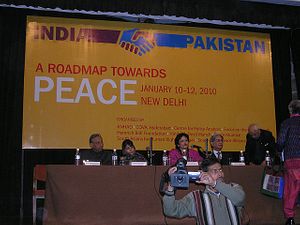

Then there are Track II dialogues which bring together individuals from various professional backgrounds: politicians, retired diplomats, defense personnel, retired intelligence officials as well as academics. Not all, but many of these Track II events are held overseas to circumvent the visa issue. It would be unfair to dub all Track II dialogues as failures, since some of them have made constructive recommendations, especially with regard to the need for engagement between both countries. Yet there are some fundamental drawbacks to the current type of Track II engagement that have led to the process being mocked by large sections of society in both countries.

Most of the individuals involved in the process are from privileged backgrounds, and cannot claim to represent a large section of public opinion. This has resulted in the Track II community being viewed as the “usual suspects,” who congregate at exotic locations to make the same declarations every year, the impact of which is dubious.

Second, government officials may hit it off with their counterparts and yet have hardened positions on difficult issues, which their office or station does not permit them to modify. While they may present a softer tone during dialogue, once they return to their respective countries they resume their stated positions, and do not really contribute to the improvement of relations.

A number of steps are urgently needed in order for these dialogues to achieve anything substantial.

First, there should be attempts to include stakeholders who are not necessarily part of any “clique.” The exchanges can start by including more individuals not belonging to English-language media, especially those from the Hindi and Urdu media. While there are not many Punjabi publications in Pakistan, the Punjabi media in India has tried to play a positive role in improving bilateral relations.

Second, rather than having Track II exchanges at exotic locales or major cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad; dialogue in smaller towns which also have an interest and stake in peace, perhaps even more so due to their respective geographical location, could be advantageous. One would imagine that small towns such as Sargodha, Chiniot, Sukkur, Nowshera and Sibi in Pakistan; and Ludhiana, Faridabad, Ambala, Bhiwani, Hisar, Barabanki and Bhopal in India would be more representative of public opinion, rather than the cosmopolitan urban centers on either side of the border. It may also be helpful to choose locations where there have been large-scale migrations.

Third, while those who make a contribution to improved relations should be included, there should be some sort of a rotation policy, where those who are not as committed are removed and newer faces are brought in, and the dialogue is expanded. There should be increased interaction between small business owners, trade unions, labor unions, lawyers from small towns, religious leaders from all communities and writers from the regional media.

Finally any such interaction should not be focused on a predetermined agenda. The idea is to let people meet and make up their own mind about whether they want peace and a relationship based on pragmatism and not emotion.

The purpose is to get to know each other in a substantial manner. By bringing more localized stakeholders on board, the idea would be to emphasize the multiple identities of the dialogue’s counterparts, and thus build more lasting and fruitful bridges.

Tridivesh Singh Maini is a Senior Research Associate with The Jindal School of International Affairs, Sonepat (India). Yasser Latif Hamdani is a lawyer and writer based in Lahore, Pakistan. He has authored the book Jinnah; Myth and Reality. He was one of Asia Society’s India-Pakistan Young Leaders for 2013.