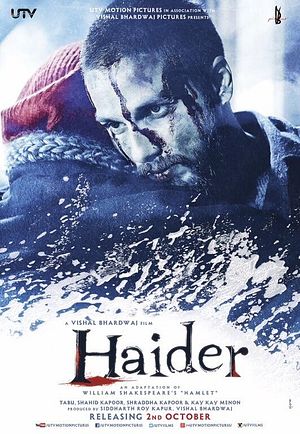

It has been called the “standard bearer for a generation,” a deeply stirring look at Hamlet and Kashmir. It is the film Haider. Set in Srinagar in 1995, in the midst of militancy and a brutal Indian counterinsurgency, Haider (Shahid Kapoor) is shown returning home after he learns of his father’s disappearance. The Indian army has detained his father, accusing him of supporting militants. He’s on a mission to track down his father, but the haste with which his mother Ghazala (Tabu) moves on with her life and takes refuge in the arms of his uncle Khurram (Kay Kay Menon) disturbs him.

Struggling with both his unnatural love and hatred for his mother as she succumbs to the advances of Khurram, Haider makes a murderous vow to avenge his father’s death. The genius of this film is how its director Vishal Bharadwaj has managed to adapt Hamlet to a whole new setting, and yet as an audience one wonders if they are watching an entirely new story. Bharadwaj has deftly used the show-but-don’t-tell technique to give us a veiled peek at the lives of ordinary Kashmiris who have borne the brunt of the Indo-Pakistan border conflict. This is the great triumph of the film.

Indian films about Kashmir rarely stray from the established narrative, one of the Indian army courageously fighting armed insurgents determined to deliver Kashmir into the arms of Pakistan. A film about the politics of Kashmir is emotive issue – already there are calls from the right wing in India to ban the film for purportedly being anti-national and for showing the armed forces in a negative light. Political cinema is not renowned for its neutrality, nor should it be, for that is the responsibility of a documentary. Indian audiences for the most part have watched Haider and taken what it has shown us on the chin, no matter how uncomfortable it has made us. Let us not be fooled, there is a lot to be uncomfortable about.

Although the story is largely based on Hamlet, Haider borrows themes extensively from the scriptwriter Basharat Peer’s acclaimed novel Curfewed Night. The film depicts the Ikhwan, a counterinsurgency force compising mainly militants, who were armed and funded by the Indian security forces. Peer writes in the book: “They tortured and killed like modern-day Mongols. The Ikhwan … went on a rampage, killing, maiming and harassing anyone they thought to be sympathetic to the Jamaat [the Jamaat-e-Islami, a religious body supportive of Pakistan] or the separatists.” That essentially a death squad of ex militants were armed by the Indian army and let loose on the populace is a galling fact of the conflict that many Indians choose to ignore.

The film also touches upon AFSPA, or the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, a draconian measure whereby any soldier of the Indian Army can, “fire upon or otherwise use force, even to the causing of death where laws are being violated. No criminal prosecution will lie against any person who has taken action under this act.” Advocates of the law will tell you that these measures were necessary to protect soldiers in a volatile environment. This may be so but that does not excuse the crimes committed by the security forces under the ambit of this law. Ever since it was brought into law in 1991 (In Jammu and Kashmir), not a single army or paramilitary officer or soldier has ever been prosecuted for murder, rape, destruction of property, or other such crimes. It is a shameful and horrific history, about which India knows little and cares even less. What makes Haider such a special film is that, unlike other works that have dealt with the Kashmir Conflict, it does not pretend that history does not exist. There is no doubt that the security forces did torture detainees in holding cells across the state. The film has a scene where captured Kashmiris are tortured in a place called MAMA-II, a nod to the infamous torture center on the banks of the Dal Lake in Srinagar. Laws were twisted to such an extent; they ended up helping the oppressors and not the oppressed.

It is a matter of pride, then, that such a powerful political film was made in India. Haider has managed to show the average Indian the other side of the coin, how this conflict is not black and white. The only solution is to tell the story from as many angles as possible. Critics point to the fact that the story of the Kashmiri Pandits who were forced to leave their homes is missing. The story of the Kashmiri Pandits needs its own chronicler; it is not Haider’s burden to bear. One can only hope that encourages other courageous filmmakers to make more balanced films on the region. For as Polonius says: “To thine own self be true.”

Gautham Ashok is a postgraduate student of International Affairs at the Jindal School of International Affairs in India.