For all the fraught relations within Central Asia, there are perhaps none frostier than that between Uzbekistan President Islam Karimov and Tajikistan President Emomali Rakhmon. The rancor, it would seem, is as much geopolitical as it is personal. Not only does Uzbekistan remain vociferously opposed to Tajikistan’s planned Rogun Dam – which would both stand as the world’s tallest and allow Tajikistan further leverage over Uzbekistan’s hydro resources – but, just a few years ago, Karimov and Rakhmon apparently got into something of a brawl after a testy exchange. (According to reports, Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev managed to wrest the two from one another.) Toss in a mined border, undelimited stretches between the two countries, and a Russian military backing Dushanbe, and you’ll understand why relations between the two have been strained further than others within the region.

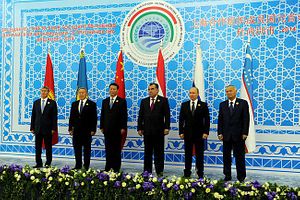

Thus, when Karimov announced he would be heading to Dushanbe last month, heads turned. Rather than spearheading an infrastructural project or announcing some kind of economic investment, Karimov landed in Dushanbe at the behest of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Alongside heads of state from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, China, and Russia, Karimov and Rakhmon found themselves at the same table for the first time since 2008. Much of the spotlight stood with discussions between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping, and all the more after further American and European Union sanctions came against Moscow. Yet the meeting between Karimov and Rakhmon, for those watching the region, stood just as interesting. Not necessarily for any agreements that could potentially come – there was little likelihood Tajikistan would budge from its push for Rogun, or that Uzbekistan would move from its opposition – but for the mere fact that it’s taken place.

And that points to a larger reality, and purpose, for the SCO. For years, observers and participants alike have wondered at the SCO’s purpose. Is it a talk-shop? Is it an anti-NATO? Is it a legitimization for Chinese hegemony in Central Asia? These questions, to be sure, remain, piling on one another as the group pushes forward. But even if those questions still stand – or even if questions on security now come to the fore, following ISAF’s pullout from Afghanistan – it seems clear that the SCO can act, at the least, as some form of regional dialogue mechanism. If Chinese money can assuage Turkmen-Tajik railway difficulties, and if Chinese needs can help tether the region via a sprawling pipeline network, it should perhaps be unsurprising that the Chinese-led SCO can morph, or has morphed, into the most substantive regional grouping in Eurasia. (It is already the most influential, as Fyodor Lukyanov recently observed.) The SCO stands as the only supra-regional organization that has brought Rakhmon and Karimov to a tête-à-tête in the last half-dozen years. For a region as fractured and tense as Central Asia, any mechanism that can midwife dialogue – between Karimov and Rakhmon, no less – remains one worth following.

Casey Michel is a graduate student at Columbia’s Harriman Institute, focusing on post-Soviet political development. He can be followed on Twitter at @cjcmichel.