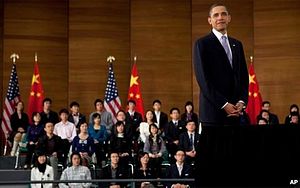

With U.S. President Barack Obama in Beijing preparing for a summit meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, China appears to be embracing the concept of rules-based governance. That could be good news for a U.S. administration eager for deliverables in its “rebalance” to Asia.

At the conclusion of the Fourth Plenum of the Communist Party’s Central Committee in late October, Xi Jinping presented a decision document outlining a new policy agenda based on “governing in accordance with law.” Although at first blush the decision seems a strictly in-house exercise in cleaning up the ruling Communist Party, it may present a new opening for the United States to engage China on rules-based approaches to global challenges.

The Fourth Plenum agenda is primarily about the Party’s domestic governance. The announced legal reforms are designed to constrain wayward bureaucrats, improve transparency and fairness in the judicial system, and generally make the Party a more effective governing machine. They aim to improve the Party’s credibility among the Chinese public at a time of economic slowdown and social transition. To that end, the Plenum decision endorses an approach to governance in which rules play a central role – constraining lower-level officials, building public trust in the legal system, and maintaining stability through more accountable governance.

But a closer look at the Fourth Plenum reveals subtle implications for China’s foreign policy.

For starters, the text of the decision itself contains clues about what Beijing wants in its foreign relations. Among other things, the Party has committed to:

“Vigorously participate in the formulation of international norms, promote the handling of foreign-related economic and social affairs according to the law, strengthen our country’s discourse power and influence in international legal affairs, and use legal methods to uphold our country’s sovereignty, security and development rights and interests.”

There are many possible meanings embedded in this broad statement of policy. But at least two points stand out that U.S. policymakers would do well to consider as they approach talks with Chinese officials this week.

First, the statement suggests China’s leaders see value in using law to conduct grand strategy. They accept in principle the validity of international law and norms, and they are looking to law as a platform for dealing with a range of foreign policy issues.

Second, the statement portrays China as an increasingly important global stakeholder. The language echoes familiar Chinese rhetoric of a rising and confident power, but it also suggests Party leaders want China to be more engaged in international rulemaking.

In 2005, Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick urged China to become a “responsible stakeholder” in the international system. This rhetorical flourish has become a distinguishing feature of U.S. policy toward China. In 2012, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton lamented that China often seeks to be a “selective stakeholder” – wishing to be treated as a developing country in some cases, an established power in others – changing its tune to suit its interests from one issue to the next.

American leaders can seize on the Fourth Plenum as the implicit acceptance of the U.S. position. The Plenum’s “rhetoric of rules” can be invoked to engage China on a range of mutual challenges: climate, trade, cybersecurity, maritime disputes, terrorism, North Korea, and more. As Secretary of State John Kerry reiterated last week, U.S. officials have long urged China to come to the table to develop “common rules of the road” on economic and security issues. And the Obama administration has already endorsed the view, shared by China, of the need to adapt and update international rules to reflect new realities.

In short, the rhetoric of law and rules can be a shared vocabulary in U.S.-China relations. Drawing from the Fourth Plenum, U.S. leaders can impress upon China the degree to which this approach fits with the Party’s commitments toward domestic governance. After all, reining in lower-level officials is one of the advantages China could realize in pursuing rules-based solutions in its foreign relations.

The foremost danger in much of China’s foreign policy lies not in the intentions of China’s leaders, who generally accept that avoiding conflict is in their economic and strategic interests. More worrying is the prospect of miscalculation at lower levels in the command chain, and a lack of clear channels for managing conflicts. An obvious example is maritime activity near disputed islands in the South and East China Seas. In such contexts, clear rules of conduct can mitigate the risk that decisions in the heat of the moment lead to confrontation and escalation.

China’s new rhetoric of rules comes just as Chinese and Japanese diplomats have achieved a breakthrough in relations – a four-point statement of agreement concerning the countries’ longstanding rift over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. While the language of the document was crafted so that each side could claim it as a victory ahead of the APEC summit, it represents a step forward in taking a “rules of the road” approach to this important and volatile issue.

U.S. officials could take a page out of this playbook in the last two years of the Obama presidency. Obama and Xi have pledged to work for a “new model” of relations between an established power and a rising power. The rhetoric of the Fourth Plenum may give currency to a rules-based approach of delivering on that commitment.

Robert Williams is a Senior Fellow in The China Center at Yale Law School.