While the ongoing debate over the heavy presence of U.S. military forces in the southern Japanese prefecture of Okinawa continues to make international headlines – including the decades-long struggle of residents to protect their island region from unsafe aircraft, sexual assaults, and the extinction of a local sea mammal – there is another story that until now has remained almost completely untold: the use of Agent Orange and other chemical defoliants in Okinawa.

Determined to end this silence, a group of Japan-based citizens including journalists, professors, and environmental activists have been gathering evidence and speaking out regarding the existence of toxic substances, including Agent Orange, that were found to have been stored, sprayed, buried and dumped in and around Okinawa by U.S. military forces during the Vietnam War era.

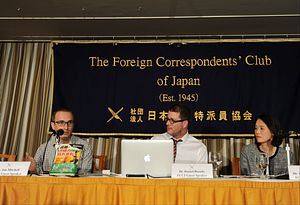

Speaking at a press conference in Tokyo on October 30, 2014, just ahead of a November 1-2 symposium at Okinawa Christian University titled “Agent Orange and the Politics of Poisons,” three of the symposium’s presenters outlined the journey to begin telling this story – and to attain justice for those who have been impacted by its legacy.

“The usage of Agent Orange and military defoliants in Okinawa is one of the best kept secrets of the Cold War,” said symposium keynote speaker Jon Mitchell, a Tokyo-based journalist who has been covering the story since 2011, and who has recently published a book in Japanese exposing this history and its subsequent cover-up.

Mitchell explained that the Pentagon’s top support base for the war in Vietnam was Okinawa, through which all manner of supplies aimed at buttressing the war effort flowed, including – according to the former U.S. servicepersons that he interviewed – thousands of barrels of the chemical defoliants that were utilized in the attempt to deprive enemy soldiers of cover in the Vietnamese jungles.

“At the time, Okinawa was a geopolitical gray zone that was not protected by either the U.S. or the Japanese constitutions, so the Pentagon felt that it could do whatever it liked there,” Mitchell pointed out.

Noting the “appalling human impact” of defoliants in Vietnam, he explained that he set out to speak with U.S. servicepersons, dioxin experts in Vietnam, and military staff and civilians from in and around the military bases in Okinawa in order to piece together the history of the use of Agent Orange and other herbicides on the island.

Mitchell spoke with more than 40 veterans who claimed exposure to Agent Orange and other toxins, which they said had also been sprayed in Okinawa in order to kill vegetation around military base roads, runways and radar sites, and who recounted that surplus supplies of the defoliants from the war effort were routinely either buried underneath the bases or dumped into the surrounding waters.

A total of some 250 U.S. military servicepersons have claimed exposure to the defoliant, he said, including those whose children and grandchildren have also shown symptoms.

Mitchell explained that a report produced last year by the Pentagon in response to his research concluded that there was no evidence of Agent Orange being present on Okinawa. This was despite the existence of soldiers’ photos corroborating their stories, as well as military documents that say otherwise, including one report noting that 25,000 barrels were stored there during the 1970s.

The Pentagon report was worthless, Mitchell said, since none of the 250 veterans claiming Agent Orange exposure were ever interviewed, no environmental tests were conducted, and no one even went to Okinawa. “The only thing that the document proved was the Pentagon’s disdain for its servicepersons, for the people of Okinawa, and for the Japanese government, to whom the report was presented,” he said.

“The U.S. government has been lying about Agent Orange on Okinawa for more than 50 years,” Mitchell added. “The land on Okinawa where defoliants were dumped now seems poisoned with dioxin – and this pollution poses a very serious threat to Okinawa’s economic future.”

He noted that large amounts of defoliants were sprayed in the city of Nago, where some residents say that local seaweed and clams were negatively impacted, and where the Pentagon tested biological weapons in the early 1960s. This is, moreover, where the U.S. is now embroiled in a highly controversial plan to build an offshore base in Henoko Bay.

“If the U.S. military was prepared to poison the land 40 years ago in Nago,” Mitchell asked, “how can we trust it to protect the environment at Henoko with its new megabase?”

“Another reason why the existence of Agent Orange and other contaminants existing in Okinawa has continued to be denied, and the environmental surveys blocked, is due to a desire to avoid ‘harmful rumors’ – which is exactly the same language being used with respect to the Fukushima nuclear disaster,” he added.

Also speaking at the Tokyo press conference was Dr. Masami Kawamura, the director of the Citizens’ Network for Biodiversity in Okinawa. She has been leading an effort to urge a government investigation and media coverage of toxic defoliants in Okinawa after 26 barrels bearing the logo of the Dow Chemical Company – an Agent Orange manufacturer – were unearthed on the grounds of a soccer field near Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa City in June 2013 during installation of a sprinkler system.

Kawamura said that the official U.S. government stance, which holds that Agent Orange was never present on Okinawa, has created a hierarchical political discourse that infiltrates downward to the governments of Tokyo, Okinawa prefecture, and local municipalities – with each of the lower entities too afraid to contradict the U.S. government’s assertions.

In an attempt to downplay the significance of the unearthed barrels, therefore, Kawamura said that the Okinawan Defense Bureau conducted only a cursory investigation, while continuing to deny the existence of any contamination – simply parroting the line from the Japanese government that “there are no defoliants,” which in turn reflects the U.S. government position.

A cross-check counter-investigation overseen by Okinawa City officials that included outside expert testimony, however, revealed that the barrels did indeed show high levels of dioxin contamination, she said – including components found in the Agent Orange herbicide, as well as traces of other defoliants – which also showed many similarities with dioxin contamination in Vietnam.

“Due to the ratio of the components, the Okinawa Defense Bureau has simply kept insisting, ‘There is no Agent Orange,’” Kawamura pointed out, “but their analysis has not taken into account the possible presence of other defoliants such as Agents Purple, Green and Pink, in the field.”

“We will continue our efforts to uncover the truth.”

Remarks were also given at the press conference by Okinawa Christian University professor Daniel Broudy, an organizer of the November 1-2 symposium, who noted that “the Dow Chemical and Monsanto corporations have continued to deny the link between defoliants and illnesses,” and that “Vietnamese survivors have continued to be denied a voice.”

Broudy said that the symposium would involve representatives from communities that have been involved in similar struggles – Bhopal, India in addition to Vietnam – in an aim to “open up public discourse regarding the political implications of Agent Orange.”

In an e-mail following the symposium – which drew some 150 participants, and also included a trip to the contaminated soccer field with members of an Agent Orange survivors group from Danang, Vietnam – Jon Mitchell commented, “People from Vietnam have painful decades of dealing with these poisons, and their hard-earned experience will help Okinawan residents to come to terms with the contamination of their own island.”

“For Okinawan residents, it’s a steep learning curve – a traumatic one,” he added. “But the inaugural symposium was a strong first step in the right direction.”

Kawamura said that the event presented a “great opportunity for Okinawa to connect directly with Agent Orange survivors, who encouraged Okinawans to keep our fight, and provided with us concrete information for our action.”

“We are just at the starting point, but we would like to continue learning from Vietnamese peoples’ experiences in particular with regard to defoliant contamination and cleanup issues,” she added. “This is such a significant moment for us.”

Kimberly Hughes is a journalist and translator based in Tokyo, Japan who has been covering grassroots movements for positive social change over nearly the past decade. Her writings may be found here.