Moscow has long declared its own Asian pivot, yet despite deteriorating Western relations Russia has yet to prove it is at home in the Asia Pacific.

As the rule of Russian czars spread to the East from Moscow into the sparsely populated Siberian wilderness, Russia became less European and more Eurasian in terms of geography. Founded in 1860, the city of Vladivostok (i.e. “ruler of the East”) was supposed to become a manifestation of this “look East” policy.

Throughout the next 150 years Russia fought wars in Asia, created alliances and sowed animosity, but it is still among the last to be listed as an Asian state. Why is that?

Though the Russian Far East is by no means occupied by the Chinese (as some alarmists in Moscow like to claim), the central government’s grasp there is much weaker than in the European part of the country. The Primorsky region is still “there” and not “here.” Psychologically it is still regarded as a type of colony, most useful for its vast mineral resources and strategic value. Russians are constantly reminded that Kamchatka is as Russian as the Red Square, but the attitude toward it has never been the same and is unlikely to be in the near future. The Far East is mostly a place you go, not where you are from.

From this estranged position of Russia’s eastern territories comes a lack of an East-looking political elite. The attention of policymakers has always been drawn toward Europe, even during the Cold War. Russian art and culture is European in nature and Russians are best known for participating in European art forms. Political and economic theories that persisted in Russia, however modified, always came from Europe, not Asia.

So it does not come as a surprise that Russia’s Asian policy has always been secondary, to say the least. Ever since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia’s closest neighbors have always been its top concern, as has been Europe, where most of its business interests still lie.

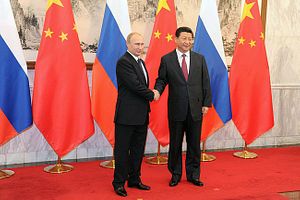

An urge to rebalance Russia’s foreign policy to the East resurges time and time again, but there is little substance to this appealing concept. In its most stripped down form, selling more oil and gas to China and more weapons to everyone else accounts for most of the Kremlin’s Asian policy these days. Many have tried to change that, and many have failed.

The reason for this failure may exist in a grave incompatibility of Asian demand and Russian supply. What is it that Asian states want? A recent policy paper (produced in Russia) sets forth the four Cs of what Asia needs for further development: consumption, connectivity, capital and creativity.

While there is still time left in the game, a draw seems the most likely outcome. Russia still has great capacity in aerospace, energy and heavy technology – all products with strong demand in Asia. Connectivity and infrastructure are also fields where Russians can play a role, given the experience Moscow has in connecting its 17 million square kilometers of land.

Capital and creativity, however, may not be modern Russia’s forte. Looming economic difficulties do not brighten expectations of seeing Russia as an FDI giant in the near future. Neither should one expect a fountain of ideas at such a time given the country’s economy. There is still quite a bit of industrialization to do, so a postindustrial creative economy is still a long-term goal.

However, Russia has a strong advantage in wooing Asian states. As the smaller countries of the region feel pressure from both the U.S. and China to choose between the two, Russia may present itself as a third option. Countries like Vietnam are getting a taste of this balancing act, making big powers compete for its loyalty while gracefully accepting gifts in trade, development assistance and investment.

Russia may make an attempt to return to Asia as an impartial but concerned international actor, promoting this new non-alignment and preventing polarization of the region. Seen as a rogue in the West, Russia may well become the peacemaker in the East.

Anton Tsvetov is the Media and Government Relations Manager at the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC), a Moscow-based foreign policy think tank. He tweets on Asian affairs and Russian foreign policy at @antsvetov. The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect those of RIAC.