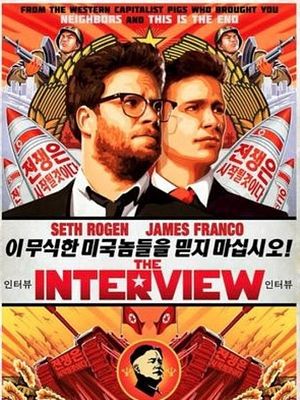

Earlier this month, Sony Pictures was hacked in a major cyber-attack by a group called the Guardians of Peace. The hackers ended up releasing a massive amount of internal Sony data — everything from emails to employee’s social security numbers. Finally, they threatened to attack theatergoers should Sony Pictures go forth with the planned December 25th release of The Interview, a satirical comedy whose central plot revolves around characters played by James Franco and Seth Rogen attempting to assassinate North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. The same group of hackers threatened to actually blow up American movie theaters should Sony release the film, prompting many to assume Pyongyang itself was behind the attacks. While it was initially unclear if North Korea was indeed responsible, U.S. officials have now concluded that the Hermit Kingdom was “centrally involved” in the sponsorship, planning, and execution of the attack. U.S. officials have also noted similarities between the malware used against Sony and that used against South Korean banks and telecommunications companies last year, further suggesting a North Korean link.

Earlier this week, the hackers delivered an additional threat promising that should Sony release the movie, an attack on the scale of 9/11 would occur: “Remember the 11th of September 2001,” their threat read. “We recommend you to keep yourself distant from the places at that time.” This threat prompted several of the United States’ largest movie theater chains to cancel plans to run the movie.

As I write this, there is well-placed, widespread outrage across the American Internet that Sony’s decision to cancel the release of this film is an unjustifiable capitulation to cyber-terrorism. By complying with the hackers’ wishes, Sony is effectively demonstrating the instrumental value of a cyber-attack toward achieving political objectives — a dangerous precedent that could encourage copycat attacks by other, more sophisticated entities. To be fair, Sony’s decision wasn’t unilateral — Sony says it was influenced by the refusal of movie theaters and other venues to show the film, given concerns about the safety of their patrons. Here is Sony’s statement:

In light of the decision by the majority of our exhibitors not to show the film The Interview, we have decided not to move forward with the planned December 25 theatrical release. We respect and understand our partners’ decision and, of course, completely share their paramount interest in the safety of employees and theater-goers.

Sony Pictures has been the victim of an unprecedented criminal assault against our employees, our customers, and our business. Those who attacked us stole our intellectual property, private emails, and sensitive and proprietary material, and sought to destroy our spirit and our morale – all apparently to thwart the release of a movie they did not like. We are deeply saddened at this brazen effort to suppress the distribution of a movie, and in the process do damage to our company, our employees, and the American public. We stand by our filmmakers and their right to free expression and are extremely disappointed by this outcome.

In addition to Sony canceling The Interview, New Regency canceled an upcoming thriller set in North Korea that was to star American actor Steve Carrell. While companies are responding to the North Korean regime’s fear tactics, there is likely no real truth to North Korea’s threats. After all, Pyongyang regularly threatens full-out nuclear war and missile strikes; there is little reason that these threats ought to be perceived as credible, if they indeed are backed by North Korea. Kim Jong-un seems to be particularly sensitive to how he is perceived on the world stage, as evidenced by North Korea’s extensive diplomatic efforts at preventing a U.N. Security Council discussion of its human rights record.

The United States needs to carefully weigh its response to this incident if it is substantiated without a doubt that North Korea was behind this attack. Current reports note that the government is “considering a range of options in weighing a potential response.” The U.S. government should treat this attack as an attack on a core U.S. industry (Hollywood), and react proportionately. This attack will likely emerge as a case study in how non-kinetic attacks sponsored by national states can not only cause economic damage, but can also stifle a nation’s core values, such as free speech and the freedom of expression. While the U.S. government cannot coerce Sony Pictures to release The Interview, it must recognize that cyber-terrorism can be immensely destructive.

For the North Korean regime and military leadership, the U.S. response must inspire a smirk of satisfaction. Pyongyang has effectively demonstrated that it can cause real economic and psychological damage in the United States with its cyber-warfare capabilities — an as-yet underutilized tool in its asymmetric warfare portfolio. Most troublesomely, the attack on Sony Pictures demonstrated a good deal of sophistication. This means that we may see North Korea turning to cyber attacks in the future to protest its treatment by the international community. Where Pyongyang’s threats in the past were largely brushed off as angry fist-pounding, the Sony saga has shown that the Hermit Kingdom can effect real damage.

This incident could additionally cause a flare-up over cyber issues between the United States and China. Although relations between Pyongyang and Beijing are not too hot at the moment, North Korean cyber-attacks in the past have been traced to mainland China. Additionally, it is likely that the know-how required to carry out a sophisticated cyber-attack originated in China. One U.S. intelligence official said that the Sony Pictures attack demonstrated “sophistication that a year ago we would have said was beyond the North’s capabilities.”

North Korea has officially denied any involvement in the attacks, though U.S. officials are practically convinced of state involvement. According to the New York Times, North Korea left open the possibility that the attacks could have been the “righteous deed of supporters and sympathizers” of the regime.

As a closing thought, though it might not be an element of hard-and-fast military strategy, juche, or songun, you’d think the North Korean military higher-ups that okayed the attack would have heard of the Streisand Effect by now.