Recently I went to Japan as part of a small group of American academics and researchers interested in Japanese foreign policy. During the trip, we met with officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Defense, Coast Guard, and Cabinet Secretariat to discuss recent developments in regional security and U.S.-Japan relations. Unsurprisingly, many of the meetings focused on the Senkaku Islands (known in China as the Diaoyu Islands). Here’s what I learned:

There’s Still “No Dispute”

First, during the meetings, it became apparent that at least some media outlets in the West haven’t been sufficiently clear about current Japanese policy. Tokyo’s longstanding position has been that there’s “no dispute” over the Senkaku – the territory belongs to Japan and there is nothing to negotiate or even talk about. This view is of course controversial in China, which also claims the Islands, and the two sides have been engaged in a fairly protracted and tense standoff as a result. To reduce tensions and improve bilateral relations, China and Japan jointly released a four-point statement on November 7. Sources such as the The New York Times suggested that the statement reflected a shift in policy: Japan would now recognize the existence of a dispute. On this view, the recent statement was a major concession to China because recognizing a dispute might open the door to bilateral negotiations that could have only one effect – namely, an erosion of Japan’s effective control over the territory.

But these media accounts are simply inaccurate. Japan has not changed its policy; every official who addressed the issue stated unequivocally that Tokyo continues to maintain that there is no dispute.

The principal source of confusion is that China and Japan both released their own versions of the four-point statement – one each in their respective native languages, and one each in English. In relevant part, China’s English-language version states that “the two sides have acknowledged that different positions exist between them regarding the tensions which have emerged in recent years over the Diaoyu Islands and some waters in the East China Sea, and agreed to prevent the situation from aggravating through dialogue and consultation and establish crisis management mechanisms to avoid contingencies.” Japan’s English-language version, by contrast, states that both sides “recognized that they had different views as to the emergence of tense situations in recent years in the waters of the East China Sea, including those around the Senkaku Islands, and shared the view that, through dialogue and consultation, they would prevent the deterioration of the situation, establish a crisis management mechanism and avert the rise of unforeseen circumstances.” While similar in various respects, these texts carry different meanings on significant issues. Most importantly, China’s version suggests the two sides acknowledge that they hold different positions not only regarding tensions in the waters surrounding the Islands, but also over the Islands themselves. It doesn’t take much to go from there to the conclusion that Japan now recognizes a dispute.

How, then, to make sense of the recent statement in light of the longstanding and – it turns out – current Japanese position that there is no dispute? First, disregard the Chinese versions of the statement – Tokyo did not approve them, so they cannot bind Japan or operate as official representations of the Japanese position. They are simply what China wants to tell Chinese nationals and the international community about Japan’s position. Second, pay close attention to what Tokyo said. It is noteworthy that the Japanese versions never state that Japan recognizes a dispute over the Senkaku Islands. Instead, they express simply that the two sides “recognized that they had different views as to the emergence of tense situations in recent years in the waters of the East China Sea, including those around the Senkaku Islands.” The different views, in other words, do not concern the islands themselves, but the waters that surround them, and do not concern sovereignty per se, but rather the “emergence of tense situations in recent years.”

What, specifically, are the different views to which Japan refers? I put this question to an official at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who explained that they consist of the Chinese view that tense situations exist because Japan purchased the Senkaku Islands in 2012, and the competing Japanese view that these situations exist because China has set up an Air Defense Identification Zone that encompasses the airspace above the Islands and sent scores of vessels into the surrounding waters. Strictly speaking, recognition of disagreement on these points is independent of whether Japan recognizes a dispute over sovereignty, so the longstanding policy continues.

Coordination Presents a Challenge

From meeting with various government officials it also became clear that Japan’s greatest concern involves a so-called “gray zone” incident – a seizure of the Senkaku Islands by paramilitary Chinese fishermen or other ambiguous actors. From the Japanese perspective, such an incident would require difficult decisions about whether and when to shift from a police response to one that involves the military. Leaving the matter to the Coast Guard, which has close to no weapons, creates a risk that Japan will be unable to extricate potentially well-armed intruders, but handing the matter over to the Self-Defense Force creates a risk of involving the People’s Liberation Army and starting a war.

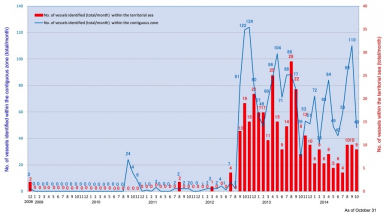

At the moment, there are reasons both to discount and credit these fears. On one hand, while the number of Chinese incursions into the waters surrounding the Senkaku Islands has been significant in recent years, it has declined. The chart below* reports the number of incursions by Chinese vessels into the waters around the Senkakus in 2013 and most of 2014. Note the red bars, which depict the number of vessels that entered territorial waters ranging from 0 to 12 nautical miles from the islands’ coast. The downward trend shows that China is not sending as many vessels into the most hotly contested area, and with recent signs of a détente there is reason to think that a sharp uptick is unlikely in the near future. Insofar as these developments signal a Chinese desire to avoid conflict, the risk of a gray-zone incursion seems limited, at least for now. Of course, the blue line does not trend downward to the same degree, but it is a less significant measure of the risk of conflict because it represents vessel entries into the contiguous zone (12 to 24 nautical miles from the coast), which are not as provocative.

*Chart courtesy of the Japanese Coast Guard

On the other hand, there are a couple of reasons for concern. First, incursions of any frequency are problematic because they create a risk of conflict through miscalculation. Second, I left Japan with the sense that important preparations have not been and will not be undertaken. I was told, for instance, that the Coast Guard and Maritime Self-Defense Force do not coordinate or engage in joint training in anticipation of a possible gray-zone incident. And I was told that Tokyo and Washington are not actively involved in any joint planning with respect to this type of threat, even though the United States has a treaty obligation to defend Japan in the event of an “armed attack” on the Senkaku Islands. In fact, Coast Guard officials explained that Japan does not even seek U.S. participation in preparations because a Chinese perception of U.S. involvement would substantially escalate tensions. This concern is reasonable. One of its consequences, however, is a risk that unforeseen interagency and bilateral logistical challenges will complicate U.S. and Japanese efforts to execute an effective response.

The Yaeyama Islands Are a Future Hotspot

Finally, the trip made clear to me that Japan’s Yaeyama Islands are a likely source of future friction. These islands, located southwest of Okinawa, are of tremendous strategic significance because they are inhabited and closer to mainland China, the Senkakus, and Taiwan than any other part of Japan. One of them – Ishigaki Island – is also home to an airport that could serve a military function. At present, Japan has virtually no military presence there, but that will change. Tokyo broke ground for a new radar base on Yonaguni this past April, and scholars at the Japan Institute of International Affairs explained to me that there is a long-term goal also to deploy the military to Ishigaki. Many of the locals apparently welcome these developments both because they see a larger military presence as a source of economic opportunity and because China has interrupted their use of fishing grounds around the Senkaku. How China responds could significantly affect future security in the region.

Ryan Scoville is Assistant Professor of Law, Marquette University Law School.