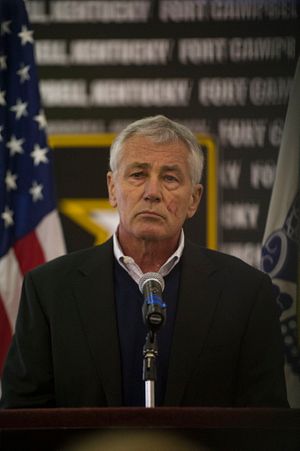

U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s resignation, like so many other topics, sparked many online discussions comparing China and the United States. I have always had my doubts about the promotion and resignation mechanisms for Chinese officials. The other day, some government workers told me that since the current administration intensified its anti-corruption campaign, Chinese officials and cadres in more than a few places are delaying things while observing things from the sidelines. That turned my doubts into worries. Under the anti-corruption campaign, we can arrest those who break the law, but we can’t do anything about those officials who are passively slow-rolling policies.

No matter the political system and form of government, there will always be some leading officials who have personal problems, or who disagree with the policies of top leaders. In the U.S., all you have to do in that case is submit your resignation – there’s a system in place to allow officials to step down. Hagel ostensibly resigned because of “personal reasons,” but in fact it’s clear to everyone that he had some disagreements with White House policies, which made him a lonely figure in high-level national security meetings. Obama’s Democratic Party suffered a big loss in the midterm elections, which usually means some high-level officials will resign. So it’s good timing for Hagel to step down – with his resignation, Obama will have the space to bring in new blood.

In the U.S., a resignation does not mean the end of an official’s political life. They can gain a new position once an opportunity arises, perhaps when a new administration comes into office. Former officials can turn to business or enter a think tank, and the older, deeply experienced ones can sit at home and write their memoirs (in fact, right now I am reading the memoirs of former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld). Those are pretty good choices. In each U.S. administration, there have been many officials that have resigned, allegedly for “personal reasons” but actually because of political reasons and differences of opinion. Generally, top leaders will politely praise the resignees, while former officials will not stir up trouble while the administration is in power – those memoirs will be published a few years later.

It’s a mark of political civilization when officials are able to be promoted and to resign freely. By comparison, China really needs to perfect its system in this regard. China should allow some officials to willingly resign and step down, especially during times when there are great changes in leaders’ policies. For a long time, it’s been an unspoken rule in China that being an official means making a fortune. It’s not really the fault of those people who want to gain power and become rich; China has been this way for thousands of years. Everyone wants to both be promoted and become wealthy; it’s human nature. People like Zhou Yongkang and Xu Caihou, who hold the power of life and death and amass a massive fortune because of it, are rare marvels in the world, extreme examples of “Chinese characteristics.”

The media reported on the resignation of two county-level cadres. One was Zhou Hui, the assistant magistrate of Pingyang Country. After he stepped down, Zhou’s resignation speech circulated online. “After my resignation was approved, I could let out a long sigh of relief,” Zhou said. “All those thoughts that have been turning over in my head for over six months finally came into being just as I had imagined.” The other official was a party secretary from Pingjiang in Hunan province. He resigned after being given responsibility for a thermal power project.

One of these men wanted to follow his own dreams while the other stepped down largely because of new responsibilities. Both of them deserve encouragement. Unfortunately, they were both low-ranking officials. I wonder, if the resigning officials had been a bit higher in rank, like Zhou Yongkang or Xu Caihou, would they have gone to work for the oil industry or to open a bank? Then they wouldn’t have had to damage the political system and the army for so long. Reports say that cash was piled up like mountains in Xu Caihou’s house. A friend said that Xu was pretty cooperative, unlike Zhou Yongkang – Xu honestly recorded a hundred pages listing those officials who bribed him. Now Chinese netizens are very curious: what names are on that list?

Truthfully, that shows a lack of understanding of Chinese politics! How can you ask “What names are on the list?” You should ask what names aren’t on the list. Xu Caihou was the incredibly powerful vice chairman of China’s Central Military Commission – once he started taking bribes, please tell me how many of his subordinated would dare not to give him something? Unless your backer was even more powerful than Xu, if you were his subordinated and you didn’t send a gift, that’d be more dangerous than going off to battle. Even if you didn’t actually pay a bribe, you couldn’t avoid sending him some small favors. The same logic applies to Zhou Yongkang – if you’re not giving him gifts, it’s only because you are too low-ranking.

Right now, the rare officials that we see resign are probably stepping down because they can’t take the pressure, or because they don’t like to taint themselves with a bad environment. When we see even people who are used to political corruption start to resign, that will mean that President Xi’s anti-corruption campaign is really working. Of course we should allow officials to resign. We shouldn’t make them adopt the attitude that, many years ago, applied to the intelligence community: come in standing up, go out lying down. We should give those capable officials who made the wrong choice a chance to resign. Those officials who don’t want to continue don’t have to worry about resigning – over the coming years, those vacancies will be filled by people who truly want to do the work. Thanks to this selection process, our cadres really would be a bit purer.

This piece originally appeared in Chinese on Yang Hengjun’s blog. The original post can be found here.

Yang Hengjun is a Chinese independent scholar, novelist, and blogger. He once worked in the Chinese Foreign Ministry and as a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington, DC. Yang received his Ph.D. from the University of Technology, Sydney in Australia. His Chinese language blog is featured on major Chinese current affairs and international relations portals and his pieces receive millions of hits. Yang’s blog can be accessed at www.yanghengjun.com.