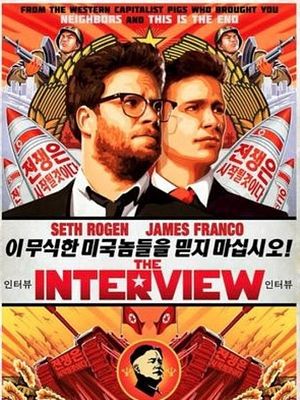

On Monday, North Korea experienced prolonged network outages that effectively severed the already-isolated state from the Internet at large. The outage came shortly after the United States formally leveled accusations against the regime in Pyongyang for backing the hackers that broke into Sony Pictures’ servers and threatened to attack U.S. theatergoers should Sony move ahead with the planned release of The Interview — a comedy featuring the assassination of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un as its climax. The North Korean outage also comes after the U.S. government promised that it would seek to respond “proportionately” to what U.S. President Barack Obama described as an act of “cyber vandalism.”

As of this writing, North Korea’s Internet access has returned after a nine-hour outage. Global network monitoring experts described the scale of the outage as serious, with one analyst at Dyn Research telling CNN that the outage was as if “North Korea got erased from the global map of the Internet.” As of yet, no one has formally claimed responsibility, but most observers are suggesting that the outage could have been orchestrated by the United States as part of its promised response. The U.S. government, as expected, is remaining tight-lipped on the matter. “We aren’t going to discuss — you know — publicly, operational details about the possible response options or comment on those kind of reports in any way, except to say that as we implement our responses, some will be seen, some may not be seen,” Marie Harf, a U.S. State Department spokesperson, told reporters.

Following the initial accusation toward North Korea, I wrote in The Diplomat that the United States needed to respond proportionately lest it set a precedent that cyber attacks against critical U.S. industries would go unpunished. If the United States’ government sponsored this retaliatory attack, it will send a message that serious cyber attacks would not go unpunished. In the case of North Korea, a proportional punishment is particularly tricky. Sanctions aren’t really an option given that Pyongyang is already essentially economically severed from the global economy. Similarly, North Korea, a state with Internet protocol (IP) addresses numbering in the low four-digits by some counts, does not rely on the Internet for any critical economic or bureaucratic purposes (the U.S. and most developed economies boast IP addresses in the multi-billion range). The government maintains an Intranet and the average North Korean citizen does not have access to the Internet at large.

Keep in mind also that preliminary network analyst impressions suggest that the outage in North Korea was caused by a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack, a relatively benign and unsophisticated method of cyber disruption. One monitoring agency, Arbor Networks, recorded DDoS attacks against North Korea before the U.S. government formally charged North Korea as the source of the attack. DDoS attacks are commonly used by cyber “protest” groups such as Anonymous to temporarily cause severe outages, bringing down websites. Simply put, a DDoS is a sloppy, unsophisticated method of bringing down a network and doesn’t befit the work of a U.S. government agency. As the Arbor Networks analysis notes, “Much like a real world strike from the U.S., you probably wouldn’t know about it until it was too late. This is not the modus operandi of any government work.” I buy this. Consider the sophisticated of something like Stuxnet and you’ll see why it’s highly unlikely that the U.S. government would resort to a paltry DDoS to bring about a nine-hour outage in North Korea.

The saga surrounding The Interview is far from over. North Korea continues to deny that it had anything to do with the attacks. Meanwhile, President Obama has criticized Sony Pictures for succumbing to North Korea’s threats and abstaining from releasing the picture. Sony’s CEO responded to the president by shifting blame onto national theater chains and the public. It’s worth noting that the White House is not calling the Sony hack an incident of cyber terrorism or cyber warfare. Describing this incident as “cyber vandalism” is an important distinction. Simply put, it’s not warfare because it doesn’t support an adversary’s military objectives (North Korea’s in this case — see Brian Fung’s more detailed treatment of this topic in the Washington Post).

The “cyber terror” tag is a little bit trickier since it doesn’t really have a formal definition (at least, per the Pentagon), and with the “terror” tag being liberally used to describe a variety of incidents, one wonders if any real meaning remains. On one hand, that the Guardians of Peace (the name of the hacker group that attacked Sony) would threaten to physical harm American theatergoers, resulting in national theater chains refusing to run the film does suggest terroristic intentions. Most definitions of terrorism, however, involve the attainment of political goals as an ultimate objective. That wasn’t the case here.

Let’s assume that the United States was responsible for the outage. Despite the many ambiguities about this incident, it will likely serve as an important case study in inter-state cyber retaliation. If the United States’ government did indeed sever North Korea from the Internet within a week of determining that a major cyber attack originated within its borders, it would send a powerful message to other would-be state sponsors of cyber attacks. We know, thanks to Edward Snowden’s leaks, that the United States’ National Security Agency (NSA) “accidentally” managed to cause an Internet blackout in Syria by bricking a core router (a technically distinct method from a DDoS). In a sense, if this outage was a U.S. government response, it was disproportional and an instance of escalation. Severing an entire country from the Internet in retaliation for an attack against a private entity is not a response of equal magnitude to the initial offense. That said, sometimes disproportionate retaliation leads to future deterrence. That could have been the goal here.