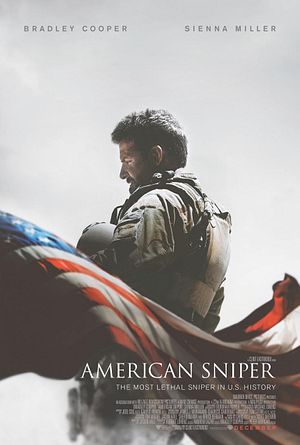

I received a number of interesting and provocative messages in response to my recent piece “American Sniper and What it Says about Civil-Military Relations in the U.S.” Several readers questioned my assertion that the U.S. public’s hero worship of anyone in uniform is not something accidental, but the logical consequence of the creeping politicization of the U.S. military by politicians and the media, which routinely exalts every U.S. service member as an exemplar of traditional American values. I will not try to restate my entire argument here. My central point is a simple one and has been succinctly summarized by U.S. Army Captain, Benjamin Summer, in June 2014 in the Washington Post: “Not every service member is a hero. The quicker we realize that, the quicker we start creating a political environment that can foster genuine debate and answer the difficult policy problems we face.”

What I have been trying to argue in a number of posts (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) is that we need to scrutinize how we think about the Armed Forces of the United States and to use our reflections to cultivate sound domestic and foreign policy.Thinking it over, I want to consider what might be the source of the not-uncommon American urge to view its wars as morality tales of good and evil and its soldiers as Homeric protagonists of right and wrong.

In this regard I found one response helpful:

“The author is trying to uncover the purported contextual neutrality of military activity. The Kipling citation and the reference to Lee and Rommel help to illustrate the complexity of assigning values to the things men (and now women and children) do on the field of battle . . . [b]ut is it possible to define any action within the limits of a moral vacuum? Can facts be distinguished from values? (…) Unless one wants to play the extreme skeptic and argue that what happened on the beaches of Normandy or the sands of Iraq has no meaning at all, we humans will try to make sense of senseless slaughter. Moral culpability and heroism are not easy to define. The contentious reactions to American Sniper are part of the ‘terrible labor’ of deciding the moral meaning of what we do. To lose sight of this task, or to deny its possibility, is to live in a world where ‘war is peace, freedom is slavery, and ignorance is strength.”

My take from Egocogitans’ comments is that it is our duty as citizens of a modern democracy to religiously question and examine the values and beliefs that are dearest to us, lest they become our own mad fantasy, as seems to be a current trend, and infect the formulation of sensible political judgment.

Yet, at the end of the day, there is no simple escape from assigning value to and passing judgment on collectively sponsored hostile deeds. It is a vexing paradox that we seem to need to give noble meaning, or at least, plausible justification, to the actions and sacrifice of those who kill on our behalf because they are the frontline defense of our pluralistic, liberal values . Without an effective corps of Willing Warriors who believe in Our Cause, we would be in danger of not being able to lethally react when our own constitutive ethos is violently attacked.

But how do we foster a public that engenders G.I Joes and Janes, primed for national defense, and, when needed, war?

It might be argued that pugilism trumps philosophy in the education of battle worthy guardians. For example, the commonly acclaimed “Greatest Generation” (after the bestselling book by the American news anchorman, Tom Brokaw, in which he recounts and enshrines the sacrifices and heroics of the WWII generation) were to varying degrees, and by the standards of current opinion, often racist, chauvinistic, bigots. Their bigotry supported vicious racial segregation, religious intolerance, and sexual discrimination at home but also induced patriotic citizens who fervently battled and defeated Japan and Germany.

A vital and deeply imbued prejudice, a Noble Narrowness, as it were, can inform and inspire a people with the resolution and confidence to do great things for the public good. Socrates mythologized how most humans love and will defend their cave and its artificial light. The television comedy “All In the Family” satirized the bigotry of Archie Bunker, who typified many of the prejudices and the moral perspective of the Greatest Generation. This is an example of the paradox described above played out in everyday life and the unreasonable rationalistic urge to bring Enlightenment to the culture sustaining man cave of ignoble bigots.

If all our prejudices, high, low and middling, are deconstructed , what do all of us who are not all wise rely on as the basis of our actions and judgment?

Drum roll: Political Correctness, the ruling prejudice of the day; that is, whatever opinions are taken to be acceptable by the majority or dominant societal forces is foisted upon us as the last Modus Operandi standing. But conventionalism is merely group assertion, and a group can be crazy or blind (akin to a ” herd of independent minds”, as Harold Rosenberg once put it). If we have any chance to identify, or at least, clarify the rough edges of this from that, we need a balanced human perception that recognizes the fundamental ambiguity in the world and seeks tirelessly to discern more clearly the nature of given conditions and the best consequent options of prudent action.

In the 1970s, and in the retro-web salons floating about, Chris Kyle would be and is spat upon as at best a fascist tool or, more darkly, a baby killer spawn of My Lai.

However, on Fox News, existential ambiguity is illuminated by neon and blond rays of red, white and blue. In an interview with Sean Hannity, the sire of the American Sniper chuckled that he would “unleash hell” upon a film director and, I speculatively add, anyone that would dishonor his son and his patriotic values. As a giant of the Greatest Generation said in a different instance, but the same grotto, “He may be a bastard, but he’s our bastard.”

Meanwhile the movie continues to fuel the culture “war on the home front” as the New York Times states in an article today.