Researchers at a key government-funded institute in China appear to have contradicted their director to lay out a moderate, or at least undecided, position for China on the so-called nine-dash line in a recent edition of Eurasia Review. This line, which was first drawn by the Nationalist government of China before 1949, appears to demarcate the entire South China Sea as subject to China’s jurisdiction — beyond the normal provisions of international law. The article appeared several months after President Xi ordered PLA hawks back into line in late September 2014 on three sets of issues: the South China Sea, the East China Sea and the India China border.

At the official level, China has not helped its case by refusing for almost seven decades to be totally clear on what maritime jurisdiction it is claiming with its nine-dash line. This has prompted anxieties and diplomatic ructions, culminating in a formal Philippines challenge to China in the Permanent Court of Arbitration on January 22, 2013. The Office of the Geographer in the U.S. Department of State also took up the issue in a December 2014 study, “China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”, in its long standing series, Limits in the Seas.

The new article from China, in fact just a short op-ed, was authored by Ye Qiang and Jiang Zongqiang, who are research fellows at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies in China. They say that China wants no more rights than are accorded it under the Law of the Sea Convention as well as customary international law. They say that the government is still “evaluating whether or not to exercise each specific right, and the scope of the rights as well as the manner to exercise. The piece argues, “These are the reasons why China has not yet clarified the title of rights within the ‘dash-line.'”

One would not normally accord any authority to such a short article by two researchers, but it is notable for several reasons. First, because it reflects 100 percent what the best-informed specialists familiar with senior officials in China know to be the case. Second, the article appears to directly contradict what many specialists thought was the previously published position of the director of the institute, Wu Shicun, who has been cited in several places as advocating a specific legal force for the nine-dash line. But Wu, writing in Global Times in January 2014, also said that “Chinese authorities haven’t defined the nine-dashed line in a legal sense.”

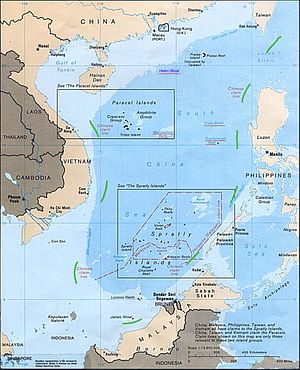

As argued in my 1998 book, China’s Ocean Frontier, China is not helping itself by refusing to define its understanding of the line. But, as also noted in the book, the “1947 publication of the unofficial boundary in the South China Sea was, in part, an effort by China to preserve its traditional or historic rights in the South China Sea in direct response to moves by other states, such as the United States in 1945, to extend their maritime jurisdiction for economic purposes beyond the previously accepted limits of the territorial sea.” The books also notes, “An equally important motivation was the registering of China’s claims to sovereignty over the islands within the u-shaped line” after the defeat of Japan and its retreat from the South China Sea.

Apart from the tumult of and territorial changes arising after the end of the Second World War, the South China Sea had been a place of colonial contest earlier. Japan had been pushing forward in the South China Sea at the beginning of the 20th century; France was the colonial power in Vietnam; the United States had become the colonial power in the Philippines in 1898; and the U.K. had even formally annexed two islands in the Spratly group in 1877. But, as Marvyn Samuels has indicated in his 1982 book, Contest for the South China Sea, a 1928 Chinese government commission concluded that at that time the Paracel Islands marked the southernmost extension of Chinese territory in the South China Sea.

With the advent of the Law of the Sea Convention, and clarification of historic rights by the International Court of Justice, and by the continuing practice of states, it will be almost impossible for China to claim (or prove) any historic rights that extend its maritime jurisdiction in the South China Sea beyond the twin regimes of exclusive economic zone or continental shelf as provided for in the Convention.

But China does have rights in the South China Sea, based on its recognized territory there (Hainan Island), its likely superior claim to the Paracel Islands, and its equal claim to at least some of the Spratly Islands (see China’s Ocean Frontier). States who want China to clarify the legal significance of its nine-dash line need to begin to understand and recognize that China does have some rights in the South China Sea.

One problem with this is that China and the United States are also in dispute, along with other states, about the right of non-littoral states to conduct military activities in another country’s EEZ and about the rights of non-littoral states to conduct (aggressive) patrolling for intelligence collection purposes in the EEZ. That is a bigger issue to which any final settlement of China’s maritime frontier is now hostage and clouds judgments outside China of the lawfulness or otherwise of its positions.