In the preface to his book Anti-Access Warfare – Countering A2/AD Strategies, Sam J. Tangredi notes: “This is admittedly a book written with an American-centric point of view. It is a point of view for which I make no apologies because – unlike many of my counterparts in the academic world – I believe that there is no such thing as value-free or value neutral research in international relations (…) all social scholarship (…) is affected by the personal beliefs (…) of the researcher.” His bias, he admits, is that of a former officer in the United States military.

Tangredi’s observation gets to core of the problem of objective defense analysis: How do you make sure that your analysis reflects the true nature of a military situation, rather than a distorted perspective on what is happening influenced by personal beliefs? This is the age old philosophical debate between what is and what ought to be, facts versus values, or positive versus normative statements. Some Marxists would argue that, in reality, there is no distinction between facts and values. While not taking this extreme position, I do think that much of American (and Western European) defense analysis is biased and we often take “what ought to be” for “what is.”

For example, most analysts assume that, given China’s weapons arsenal, regional ambitions and geopolitical situation, the Chinese Navy (PLAN) ought to be pursuing an anti-access/denial strategy. Eventually, over the last few years, this ought has turned into an is, i.e. we have determined that the PLAN is pursuing an anti-access/denial strategy, with very little study of actual Chinese sources on the subject (See: “The One Article to Read on Chinese Naval Strategy in 2015”).

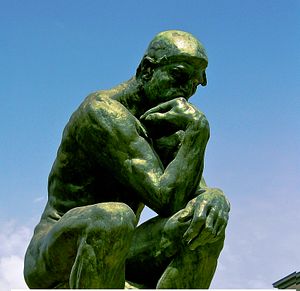

The reason behind this is obvious: We have a tendency towards mirror imaging and “dictating the conduct of war on our own terms,” according to two senior U.S. military officers. In reality, we want China to pursue an A2/AD strategy because it is the sort of war that the United States Navy can win. Recognizing this cognitive bias, however, is just the first step, is extrapolating ourselves from the trap of mirror imaging. It needs to be followed by – if we use Plato’s allegory of the cave – leaving the grotto of our own subjective beliefs and star at the sun, which is, I posit, especially difficult for defense analysts in the United States.

Considering the worldwide dominance of the English language in the hard and social sciences (although 75 percent of the world population does not speak English), the dominance of the American educational system, the global role of the American military, and the sheer size of the United States (not to mention Canada and Australia) – in short, the preponderance of American hard and soft power around the globe – escaping the cave is no easy undertaking. It is obvious that growing up in the United States, going through an American educational system throughout one’s life, serving in the United States Military for a number of years, or working in the federal bureaucracy in Washington D.C., will influence one’s perception of the world.

However, it is perhaps less obvious that Americans often cannot even escape America abroad. For example, by working for an American Corporation in a foreign country, serving in the U.S. Armed Forces overseas, working for an American university abroad, serving in the U.S. Peace Corps in a faraway place, one’s experience is still heavily influenced by American values and biases. A 1-2 year stint studying at a foreign university can hardly alleviate the impact of this pervasive American influence felt in most places.

As Robert Jervis’s notes in his book Perception and Misperception in International Politics: “If people do not learn enough from what happens to others, they learn too much from what happens to themselves.” That is, the lack of exposure to the outside world, often produces a peculiar introversion, most notably observable in Washington, where most time is spent trying to maneuver the different aspects of the Kafkaesque-like agency and inter-agency processes, while trying to fit analysis into a D.C. format (e.g., truncating the prose with various acronyms and overusing the dash as a punctuation mark), illustrating the downside of the country’s motto “E. Pluribus Unum” – out of many, one – hardly the right prescription for a defense analyst who always should think “outside the box.”

These factors combined pose a severe challenge to good defense analysis. For one thing, it makes it more difficult to develop genuine empathy (Sun Tzu’s “know thy enemy” admonishment), which Robert McNamara, in the film The Fog of War, defines as trying to, “put ourselves inside their [the opponents’] skin and look at us through their eyes, just to understand the thoughts that lie behind their decisions and their actions.” This, McNamara considers to be one of the crucial factors in making the right foreign policy decisions.

Of course, other analysts from other nations face similar biases and can be just as easily trapped within their “caves” than their American counterparts. However, as outlined above, I believe it is far easier for a Chinese or European citizen to “go native” in the United States, get immersed in its culture and develop empathy for the “American way of doing things,” than for an American in China or Europe – particularly in the field of defense analysis. Tangredi’s solution to openly admit his American bias is one way to cope with this problem. However, simply giving up on objectivity cannot be the answer. Good defense analysis requires a strive towards objectivity even if we can never genuinely obtain it.