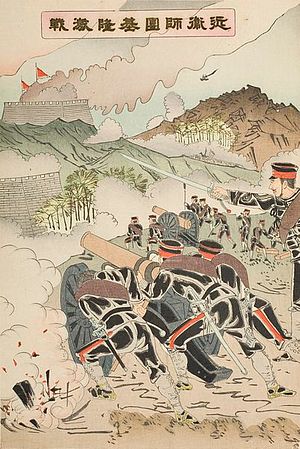

China is currently undergoing a new round of widespread and comprehensive military reforms that aim to fundamentally improve the PLA. These efforts, as detailed in the 18th Party Congress’s Third Plenum Decision from November 2013, call for such changes as increased jointness, more realistic training, and better military discipline. As China’s leaders search for guidance on how to enact these difficult reforms, they have looked deep into China’s past — all the way back to the First Sino-Japanese war of 1894-1895.

The war revolved around control over the Korean Peninsula and included two large naval engagements in which the Imperial Japanese Navy crushed the larger Chinese Beiyang Fleet. China’s defeat was swift and the aftermath was devastating, ceding important territory to Japan and hastening the end of the Qing government’s rule. Especially relevant to the PLA, China’s loss revealed the failures in the Qing’s ambitious military strengthening program, which had begun 30 years earlier, partly to counter foreign encroachment.

The summer of 2014 marked the 120th anniversary of the war. China commemorated this occasion with a flood of essays, speeches, and events analyzing the meaning of the war for modern China. During this time, Qiushi, the official journal of the CCP’s Central Committee, published a detailed analysis of the lessons learned from the war. It was written by General Fan Changlong, one of two vice chairmen of China’s powerful Central Military Commission, which exercises control over the entire military. He is second in command only to President Xi Jinping. The importance of both the author and the publication make the article worth examining in detail.

Fan begins his essay by acknowledging that China’s defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War “humiliated the nation” and “disgraced” the military. He asserts that it is important to study this painful period of history in order to educate military personnel and provide “historical lessons” that can be applicable to modern times.

Fan argues that the major takeaway of the First Sino-Japanese War is that China must build a military that can achieve victory on the battlefield in order to ensure its national security. He goes on to detail the reforms the PLA must carry out in order to reach this goal, using the weaknesses that led to defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War as examples of what to improve. His noted reforms include:

Strategic innovation: Fan points out that the Qing military relied on “outdated” military strategy and operational guidelines since Qing leaders were “ideologically conservative.” He asserts that achieving a strong military requires innovation and urges China to free itself from “conservatism, dogmatism, and parochialism” and to innovate and update military theory, strategic guidance, and military culture.

Indigenous innovation: The essay argues that although the Qing had been modernizing for more than 30 years before the First Sino-Japanese War, the national defense science and technology field was still weak since it was so dependent on other countries. He notes that although China has made great strides in indigenous development, “certain key technologies and vital sectors” remain in others’ hands. He urges China to further improve military S&T and increase indigenous innovation.

Organizational reform: Fan notes that the Qing upgraded the military’s equipment while keeping their organizational structure the same or that they “changed equipment without changing the system.” Because of this, he says, military reforms were only superficial. Fan states that the PLA must modernize military organization, reform joint operational command, improve regulations, and strengthen R&D ties between the military and civilian sectors.

Personnel reform: According to Fan, because the late Qing lacked talented military personnel, they could not truly reform the military in a meaningful way. He states that the PLA must learn from this and recruit talented personnel that truly grasp winning modern wars and conducting joint operations.

Military ethics: The essay puts a special emphasis on discipline and ethics, noting that defeat in the Sino-Japanese War was not just due to weapons and equipment, but also bad discipline, apathy, and corruption. Fan ties this to the importance of the current bout of anti-corruption efforts ongoing throughout China, including within the PLA. He specifically mentions disgraced high-ranking PLA officers Xu Caihou and Gu Junshan as examples of poor ethics and cites Xi Jinping as saying that if a military were corrupt it could not even fight battles, let alone win them.

Fan concludes by emphasizing that it is not enough to study weaknesses in the Qing military and compare them to modern shortcomings: the PLA must fully commit to actually carrying out necessary reforms. Otherwise, if it finds itself in an armed conflict, it will be unprepared and could suffer a disastrous loss similar to that of the First Sino-Japanese War.

Fan’s essay reveals several interesting trends in the PLA leadership’s thinking as the military undergoes extensive reforms. First, the fact that the PLA is looking at the First Sino-Japanese War as a template for reform confirms that China is currently focusing more on improving its organizational, personnel, and disciplinary systems rather than simply upgrading its weapons systems. Indeed, Fan explicitly points out that reform must be systemic rather than superficially technology-based. This indicates that the PLA has recognized fundamental and persistent problems in the Chinese military system that have yet to be solved, and believes that superior technology alone does not necessarily guarantee a victory in the battlefield.

Second, Fan warns that the most important lesson from the First Sino-Japanese War is that China must prepare its military to fight and win wars, or it could risk another devastating loss. Fan makes clear that a strong military is fundamental to China’s national security. This intimates the high stakes and historical significance that Chinese leaders are attaching to the latest round of reforms.

Fan’s analysis of the First Sino-Japanese War implies that Chinese leaders view themselves as vulnerable as they were in the late 19th century, while determined to avoid a similar outcome. This suggests that China’s commitment to military reform might be more than rhetorical, and that Western analysts should be closely monitoring the PLA’s progress in achieving these major goals.

David M. Liebenberg is an associate research analyst in the China Studies Division at The CNA Corporation. The views expressed here are his own.