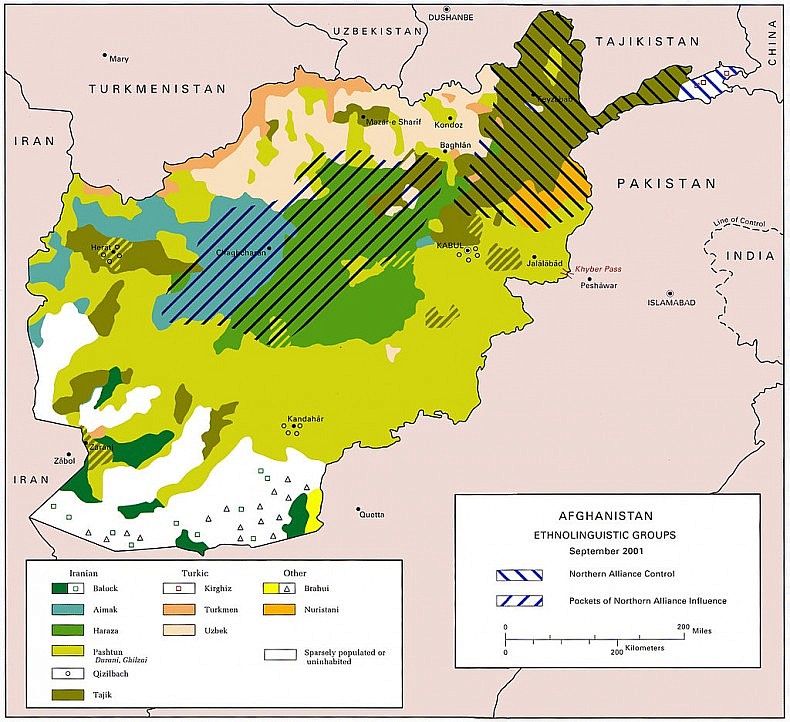

An otherwise excellent Washington Post article last week featured a map of where the Pashtun ethnic group lived Afghanistan and Pakistan that triggered a pet-peeve of mine: the fact that many non-political maps of South Asia are inaccurate. By inaccurate, I do not mean to say that they are deliberately wrong. Indeed, the Washington Post ethnic map of the Pashtuns in Afghanistan is generally correct in its basic contours. However, it is not so in its details, and the zone of Pashtun inhabitation seems splashed around throughout Afghanistan, without a level of accuracy that I would think be necessary for such a map.

This is a problem, and not merely an academic or esoteric one. Because the demographics of a province or region in places like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and India are important to demarcating provincial boundaries, governance, administration, and education, they matter. Additionally, historical maps of the region face similar problems – a lack of exactitude – that can be problematic, especially as territorial claims and arguments about traditional civilizational boundaries or spheres of influence matter in South Asia. While it is true that pre-modern mapping in South Asia did not display the level of accuracy that modern maps do and that South Asian norms of territoriality were different, there is still no reason that modern mapmakers should not try to be accurate in mapping ethnic groups and historical boundaries. A similar level of accuracy can be seen in historical and demographic maps of Europe, including those of the Roman Empire.

Why too, then, can we not expect a similar level of accuracy from maps of South Asia, and other non-Western civilizations? After all, it is on the basis of historical control that countries like China base their claims to islands in the South China Sea. Accurate, scholarly maps of the Han Dynasty that take into account a level of detail on zones of control could help us understand modern disputes. But few such maps exist. When one looks at a map of the contemporaneous Roman Empire, one finds that most maps of the Roman Empire look the same because historians and cartographers have established the contours of the empire fairly accurately. But maps of the Han Dynasty all look wildly different, as a quick Google Image search reveals.

Returning to South Asia, this is a region awash in ethnic and historical conflicts and territorial claims. Here are some examples of widely circulated inaccuracies and why they matter. Many, if not most ethnic maps of Afghanistan, for example, display the Pashtun belt as sort of “U” shaped, with Pashtuns forming the majority in western Afghanistan interspersed with patches of Tajiks and other groups. Yet, on the basis of numerous historical and contemporary reports, much of western Afghanistan including the provinces of Heart and Ghor are bastions of Persian language and culture and are inhabited mostly by Persian speaking Tajiks. There are also many wildly differing claims in both news reports and maps on whether the Shia Tajik, or Farsiwan are in the majority or minority in Herat.

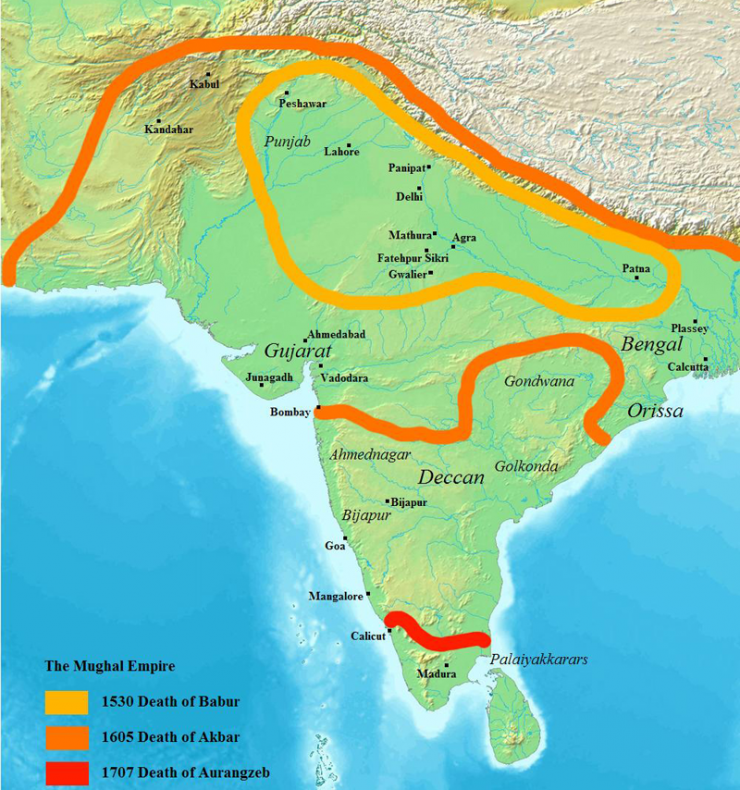

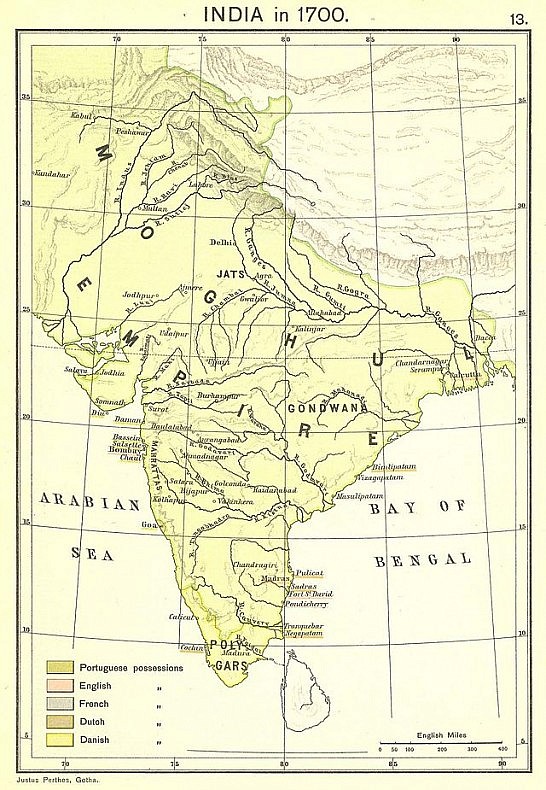

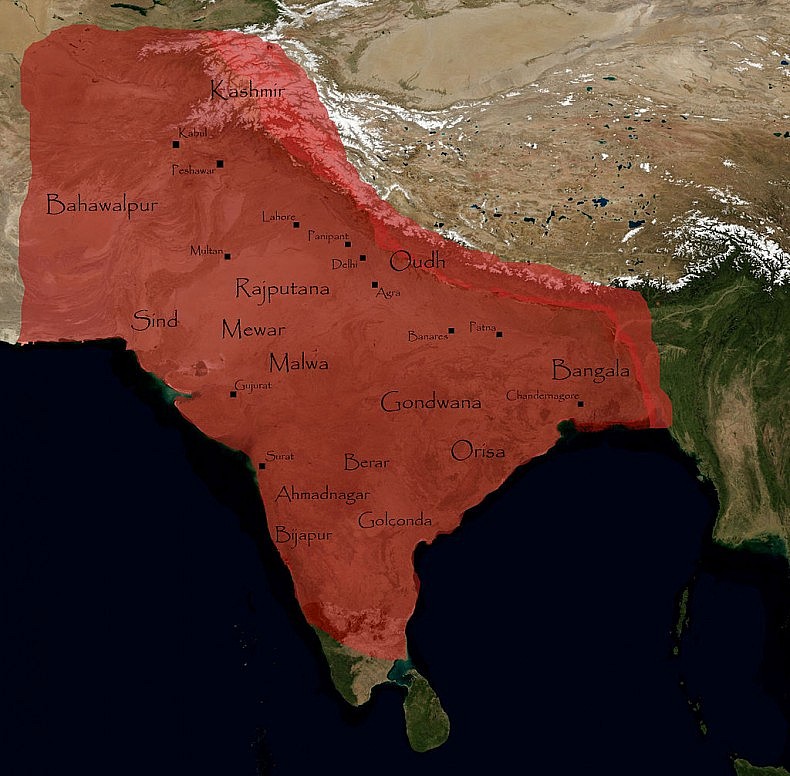

Given the proximity of Herat to Iran, it is important to accurately map its demographics if we are to understand the basis of Iran’s strong influence in western Afghanistan. Historical maps, too, also have problems. This is even true of recent states, such as the Mughal Empire. The northern boundaries of the Mughal Empire, for example, never remain the same in widely used historical maps.

Depending on the level of Mughal control over parts of today’s southern Nepal, Tibet, or northern Afghanistan, different understandings of the histories of these countries can emerge, such as China’s claim to full sovereignty over modern Tibet on the basis of its historical boundaries.

In conclusion, ethnic, religious, and historical maps of South Asia abound in generalizations and lack the level of exactitude found in Western maps. This is a problem that ought to be rectified by both mapmakers in creating such maps and the media, which ought to use more accurate maps. After all, these things matter on the ground in places like Afghanistan.

All maps via Wikimedia Commons.