Kazakhstan’s navy is celebrating its 22nd birthday this week, according to The Astana Times. While some sources cite 2003 as the date Kazakhstan’s navy was established by presidential edict, others use the 1995 date The Astana Times cites. The differing dates stem from Kazakhstan’s evolving naval personality, from a coast guard to a navy.

In 1993, the former Soviet Union’s Caspian Sea Flotilla was divided between Russia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan. The vessels served as the foundation of the Kazakh Maritime Border Guard. In 1995, the country declared itself a naval power and later that year signed a defense cooperation agreement with the United States. That year a delegation from the U.S. Coast Guard visited the country. A deal under which Kazakhstan was to receive the USCGC Mariposa, as part of the excess defense articles (EDA) program, was scrapped in 1999 after Kazakhstan sold 30 Soviet-era MiGs to North Korea.

The Kazakhstan Navy has between 13 and 15 vessels, mostly inshore patrol craft. Notably, in 2012 Kazakhstan launched its first domestically produced ship, a missile boat designated Kazakhstan, which Eurasianet categorized as the country’s first real naval ship. In February 2015, IHS Janes reported that the country’s Zenit Uralsk Shipyard is “planning to launch a fifth Project 0300 Bars-class patrol vessel for the Kazakh coastguard service in April 2016.

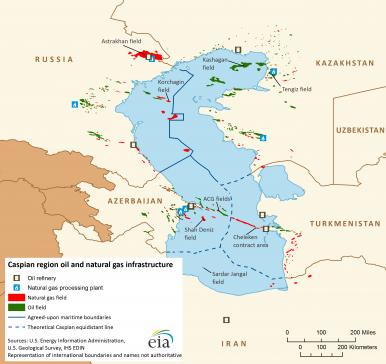

Though landlocked, Kazakhstan nonetheless has serious maritime concerns stemming from the Caspian Sea. By area, the Caspian Sea is the world’s largest inland body of water — essentially the world’s biggest lake. The Caspian Sea’s 143,200 sq miles are bordered by five states — Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Russia, and Iran. In and around the Caspian basin sits an estimated 48 billion barrels of oil and 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

The five Caspian littoral states have been in negotiations for almost a decade to demarcate the Sea, but final terms are still out of reach. How to divide the Caspian’s energy resources among the five is a difficult question. Other sticking points relate to fishing rights and access to international waters. Russia’s Volga river and the canals that connect it to the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea are a big concern for Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan.

Kazakhstan, with massive oil fields in the north Caspian, and no other way to the ocean except via Russia’s canals, has invested in building its naval capabilities over the past few years. What some have called an arms race is underway in the Caspian, with most focusing on the Iran-Russia dynamic. Joshua Kucera noted in an article for Foreign Policy in 2012 that:

The biggest reason for this buildup may be mistrust of Iran, but it’s not the only one. The smaller countries also worry about how Russia’s naval dominance allows Moscow to call the shots on their energy policies. Iran and Russia, meanwhile, fear U.S. and European involvement in the Caspian. All of this, among countries that don’t trust each other and act with little transparency, is setting the stage for a potential conflict.

Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev was hopeful after the 4th Caspian Summit, held in September 2014. What was trumpeted at the time as a breakthrough were a handful of cooperation agreements as well as agreements among the parties on the “principles of national sovereignty” and the “principles of the right for free access from the Caspian Sea to other seas and back on the basis of international law, taking into account the interests of the transit parties.” Agreeing to principles is a start, but the ultimate status of the Caspian is still up for debate. The next summit won’t take place until 2016; in the meantime, Kazakhstan plans to continue building its naval capabilities.