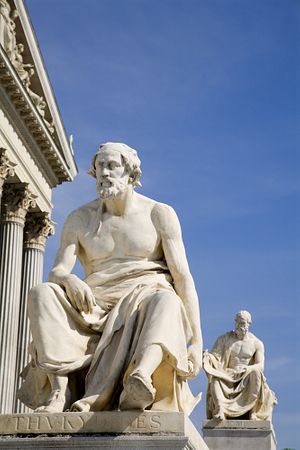

Professor Graham Allison of the Harvard Kennedy School has popularized the phrase “Thucydides’ trap,” to explain the likelihood of conflict between a rising power and a currently dominant one. This is based on the famous quote from Thucydides: “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this inspired in Sparta that made war inevitable.” This usage has even spread to Chinese President Xi Jinping who said “We all need to work together to avoid the Thucydides trap – destructive tensions between an emerging power and established powers … Our aim is to foster a new model of major country relations.” However, those like Graham Allison who talk about a Thucydides trap only capture half the meaning of the History of The Peloponnesian War. The true trap is countries going into, and continuing, war clouded by passions like fear, hubris and honor.

In Thucydides’ history, human emotion made conflict inevitable, and at several points where peace was possible, emotion propelled it forward. In the beginning, there is a set of speeches in Sparta debating the possibility of going to war with Athens. Archidamus, the Spartan king, tells the Spartan people not to underestimate the power of Athens and urged that Sparta “must not be hurried into deciding in a day’s brief space a question which concerns many lives and fortunes and many cities, and in which honor is deeply involved – but we must decide calmly.” However, Sthenelaidas, a Spartan ephor, advocated, “Vote, therefore, Spartans, for war, as the honor of Sparta demands.” The Spartans followed Sthenelaidas, which led to a war of honor and fear against the Athenians.

In the seventh year of the Peloponnesian War, at the battle of Pylos, the Athenians won a major victory over Sparta. Because of their loss, Sparta sent envoys to Athens offer a peace treaty. The Spartan envoys enjoined the Athenians to “treat their gains as precarious,” and advised that “if great enmities are ever to be really settled, we think it will be, not by the system of revenge and military success… but when the more fortunate combatant waives his privileges and, guided by gentler feelings, conquers his rival in generosity and accords peace on more moderate conditions than expected.” However, the Athenians, led by Cleon, who Thucydides described as the most violent man in Athens, accused the Spartans of not having right intentions, and made further demands on Sparta for a return of territories that Athens had previously ceded to Sparta before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, resulting in a continuation of the war.

If the United States and China fight a war, it will occur because of the same fear and honor that led the Spartans to start the Peloponnesian War, or the Athenians to continue it. Prominent Chinese scholar Ye Zicheng expressed this sense of honor when he wrote, “If China does not become a world power, the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation will be incomplete. Only when it becomes a world power can we say that the total rejuvenation of the Chinese nation has been achieved.” American exceptionalism, the conviction that the United States holds a unique place and role in human history, provides a counterpart to Chinese nationalism, and is widespread enough to be a central plank of the Republican Party’s platform.

This strong belief of a special place in the world can make a country sensitive to insult, intended or otherwise, such as in 1999 when NATO aircraft bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade during Operation Allied Force in Bosnia, killing three Chinese citizens. The United States claimed that the bombing was an accident, but few Chinese accepted this explanation, and more than 100,000 Chinese protested across the country, including attacking the American embassy and consulates. Contributing to the anti-American outrage was Chinese state media insisting the bombing was not an accident. Anti-Chinese sentiment is not as widespread or as vocal in the United States, but it is common for American politicians and pundits to portray the rise of China as a risk to America’s place in the world.

The best advice that Thucydides’ work offers is clear, do not let emotions such as hubris, fear and honor drag you into a hegemonic war, and if war does occur, do not let these same emotions cloud your judgment if there is a chance for peace. This is a hard lesson to learn, but unlike the mechanistic vision of Thucydides’ Trap it accounts for human agency and shows a path towards peaceful co-existence rather than letting passions lead the way.

Leon Whyte is a second year master candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University as well as the Senior Editor for the Current Affairs section of the Fletcher Security Review. His research interests include transnational security and U.S. alliances in East Asia.