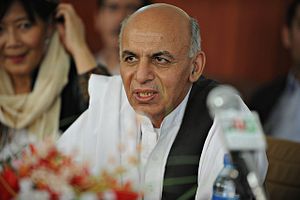

Given Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s “pivot” to Pakistan, many expect that Pakistan will have to reciprocate by either bringing the Afghan Taliban to peace talks or undertaking military actions against the group. In late May, reports surfaced that Pakistan had warned the Afghan Taliban to call off their spring offensive or face “consequences.” Media reports subsequently revealed that Ghani sent Pakistani authorities a letter asking Islamabad to cease its support for the Taliban and gave it three weeks to prove Pakistan’s commitment to stability in Afghanistan. Ghani’s current approach towards Pakistan seems to be putting all of his eggs in one basket, and there are serious doubts as to whether Pakistan will be as committed as the Afghan president wants.

Certainly, it would seem to be in Pakistan’s interests to capitalize on this opportunity and support Ghani and his campaign against militancy in Afghanistan. This shift in Pakistani policy would pave the way for longstanding stability in the broader Afghanistan-Pakistan region. By sticking with the Taliban and failing to respond to Ghani’s overtures, Islamabad will further undermine stability and fuel rivalries within the region.

Yet Pakistan has been slow to respond and Afghans worry that Islamabad may not deliver. Islamabad has a long investment in the Taliban, primarily motivated by its desire to counter India’s influence in Afghanistan. For all of Ghani’s efforts to tilt Afghanistan’s foreign policy in favor of Pakistan, compromising relations with India, Islamabad does not seem impressed. Islamabad continues to accuse India’s intelligence service, the Research and Intelligence Wing of destabilizing Pakistan from Afghan soil. Given Pakistan’s long anxiety about India – despite Ghani’s efforts to dispel this fear – many in the Pakistani military “establishment” want to continue sheltering the Taliban.

That establishment has a long history of using Islamist militancy as a policy tool to advance Pakistan’s strategic and regional agendas, and appears still to favor the Taliban. It is most likely that the military views the Taliban not as an entity inimical to Pakistani interests but as an asset that it can control.

As far as stability in Pakistan is concerned, the viable options – visible from Pakistan’s behavior – to restore peace in the country are expelling Afghan refugees and illegal migrants, permanently deploying troops in Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA), and repressing Baluch and Pashtun separatists inside Pakistan.

However, lingering conflict in Afghanistan would be detrimental to security in Pakistan, as stability in the two countries is interrelated. Indigenous groups – both Afghan and Pakistani – that enjoy sanctuaries in the border region do cooperate with each other and will host regional and transnational militant outfits, particularly the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM), their offshoots, and international partners. These groups pose a threat to both neighboring countries and their allies, including China and the countries of Central Asia.

Failing to dismantle militancy will also complicate the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a vital project for Pakistan’s economy. This would have repercussions for Pakistan’s relationship with its longstanding ally China.

Should Pakistan opt for the Taliban over Kabul, the latter would be under pressure to walk away from the the recently signed (and controversial) Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) of intelligence sharing between Afghanistan’s National Directorate of Security (NDS) and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). It would frustrate Ghani and encourage him to rethink his pivot to Pakistan. That frustration would cloud political and economic ties between Afghanistan and Pakistan, and encourage Ghani to turn to India.

In fact, going after the Afghan Taliban leadership would be a difficult task for Pakistan, as the country has already lost control of the group. But Pakistan must go after the militants. Instead of maintaining ties with non-state actors, Pakistan has an opportunity to work with Kabul. It is unlikely to come again: Other Afghan leaders would not be expected to make the overtures Ghani has. If Pakistan fails to act, anti-Pakistan sentiment among Afghans – already high – will only rise.

Rebuffing Ghani would signal Pakistan’s intention to continue its policy of interference in Afghanistan and will prolong the conflict. This policy would allow militancy to grow in the border regions and would threaten security in both Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Hekmatullah Azamy (@HekmatAzamy) is a research analyst at the Centre for Conflict and Peace Studies (CAPS) based in Kabul Afghanistan. His areas of interest include research on socio-political and security issues in Afghanistan-Pakistan region.