Pakistan has recently issued a directive to grant its national language and lingua franca, the literary vehicle of South Asian Islam, Urdu, official status. Perhaps inspired by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s use of Hindi on the world stage instead of English–common among elites in both Pakistan and India–the government of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif told the Supreme Court of Pakistan that it will shortly become mandatory for government officials to deliver speeches in Urdu, whether in Pakistan or abroad. Nawaz Sharif signed an executive order to that effect on July 6.

It may come as a surprise to many that Urdu is not already the official language of Pakistan, given that in its spoken form, it is the lingua franca of the country and understood by virtually everyone. English serves as the official language and major laws and documents are in English; at least in neighboring India, both Hindi and English share official status at the federal level. Article 251 of the Pakistani constitution, from 1973, states that “(1) The National language of Pakistan is Urdu, and arrangements shall be made for its being used for official and other purposes within fifteen years from the commencing day. (2) Subject to clause (1), the English language may be used for official purposes until arrangements are made for its replacement by Urdu.” Therefore, Sharif’s directive is in keeping with the requirement of the constitution that “arrangements” be made for Urdu becoming fully functional as an official language.

Of course this announcement has been met with some dismay by Pakistan’s elite, despite the widespread use of Urdu. Some lines of complaint have included people whining about not being able to communicate sufficiently well in Urdu, especially written Urdu, because they went to school exclusively in English. The use of English by the elite in Pakistan has led to complaints of a class divide. Yet, there is no question that the elite will continue to send their kids to special English schools and higher subjects will be taught in that language, no matter the status of Urdu. So the elite doesn’t have much to fear other than losing some privilege. As I argued in regard to language in India last year, it is both understandable and necessary for a government to at least provide basic services, laws, signage, and education in a language familiar to the majority of its population for the sake of administration and human development. In a country as poorly governed as Pakistan, with a high illiteracy rate, it is an extreme burden to expect individuals to somehow communicate in a dissimilar language.

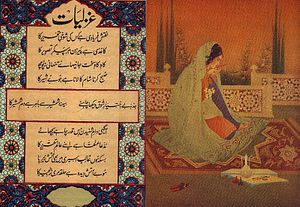

In any case, the decision has already been made, though it remains to be seen how well it will be implemented. There is much to be said for Urdu, a language with an extensive literature and over a hundred million speakers in India and Pakistan. In fact, given its widespread use as a lingua franca among Muslims in South Asia and its mutual intelligibility with Hindi, Urdu is probably the second most important language of Islam, supplanting Persian in that historical role. Together with Hindi, the combined language Hindustani or Hindi-Urdu (they share a vocabulary and grammar and only differ in terms of script and some technical vocabulary, which Urdu borrows from Persian and Arabic) is the world’s second most spoken language.

Urdu is a beautiful language with a long history. One common criticism leveled against it in Pakistan is that it is alien to Pakistan, since technically the Hindustani language evolved from the dialect of Delhi during the Mughal Empire (Urdu is the native language of less than ten percent of Pakistan’s population). However, that is not entirely true, as it was also the lingua franca of the masses of the northern half of South Asia by the time Mughal Empire, though the official language in most South Asian Muslim states remained Persian until the British Raj, which made English and Hindustani official. Although Persian is another beautiful language that has a long history of association with South Asian Islamic culture, in modern times, it has increasingly become associated with an Iranian Shia culture that is now divergent from South Asian Islam. Most Persian works by South Asian writers have been forgotten or are considered derivative and artificial and thus extraneous to the concerns of South Asia, while the same authors’ works in Urdu are well remembered in the region (for example, the poets Ghalib and Iqbal). Urdu has a distinct earthiness, vigor, and emotional rawness that is very powerful.

Hindi-Urdu, developed as a native link language in a number of South Asian cities including Lahore in Pakistan precisely because it was related to the languages of Northern India: Urdu, like them belongs to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European language family whereas Persian belongs to the Iranian branch. Therefore, because of its similarity to Punjabi and Sindhi, Pakistan’s major native languages, Urdu became the dominant lingua franca, and is essentially the only language on national radio and television in Pakistan. Additionally, Urdu holds the largest collection of works of any Islamic language. Given these facts, the increased official use of Urdu in Pakistan is reasonable, relative to multiple regional languages or English.