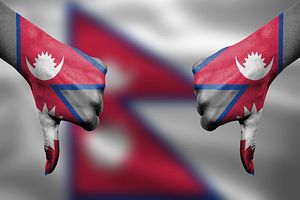

Disenchantment has been running high in Nepal, over the plan to divide the country into six provinces (down from the eight originally mooted), paving the road for a federal system. Tensions are particularly high among marginalized groups, and those from the country’s far western and plains regions.

The delineation of the provinces was mainly made on the basis of identity, but the provinces do not enjoy equal strength in terms of resource distribution or sustainability. Experts and economists have expressed doubts about the outlook for those provinces with fewer resources. The resource disparities are significant, and could have a long-term impact on development.

The 16-point deal reached among the major political parties in June finally fast-tracked the work to adopt a new constitution, although it was heavily criticized and even brought pressure from an unhappy Indian establishment. Analysts note that the political parties backed away from their earlier plan to divide the country into eight provinces. Conspiracy theorists point to a visit paid by former prime ministers, Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Sher Bahadur Deuba, to India after the 16-point agreement was signed.

Interestingly, all provinces share a border with India, whereas Province 5 and Province 2 are removed from Nepal’s border with China. Sarita Giri, leader of the Nepal Sadbhawana Party (NSP), a Madhesh-based party, argues that Province 2, which is in the Terai, or plains, region, should also have a border with China, an emerging economic power in the region. She argues that without direct access to China, the province would be deprived opportunities for trade, considered a means of wealth creation in Nepal.

Districts like Surkhet, in the Far-Western Development Region, and Banke, in the Mid-Western Development Region, are tense, with people taking to the streets to express their dissatisfaction at the delineation. In many other parts of the country, calls have been made to revisit the decision. And in fact, negotiations are ongoing to increase the number of provinces. At the time of writing, it remains unclear if an alternative proposal will be adopted. It seems unlikely, and Prime Minister Sushil Koirala has asked protesters to halt their strikes. So what can Nepal and its provinces expect in the long run?

Nepal is considered to be rich in water resources, yet it suffers from acute power shortages, which have been crippling daily life, even in the capital of Kathmandu. Provinces 2 and 5 have no hydroelectricity plants at all, whereas Province 3 and 4 have 38 and 29, respectively. Provinces 1 and 6 own 14 and 10 hydroelectricity plants, respectively.

In terms of human development and education levels, Province 2 has the lowest adult literacy rate, at just 41 percent, whereas Province 4 has a 67 percent adult literacy rate, the highest among all the provinces. Yet most provinces have their own strengths. Take Provinces 2 and 5, for instance, which have low literacy and no hydroelectricity power plants, but which are the industrial heartland of Nepal. Additionally, these two provinces, which lie mostly in the Terai, are considered to be the country’s food basket, with a food surplus that helps other parts of Nepal that suffer from a food deficit. In contrast, Province 6, in the Far-Western part of Nepal, is economically poor and lags in all areas, including education, human development, and per capita income, although it is the largest in terms of area.

The long cherished dream of a federal Nepal has come true. Still, people are disgruntled. What has gone wrong? This question begs to be understood in light of Nepal’s location, its own geography, the historical evolution of different castes and ethnic groups, and livelihoods. Nepal has long struggled to be federalized, but no serious homework was done on what basis the country should have been divided. The first Constituent Assembly was dissolved as the major political parties could not reach a consensus on the basis for federalizing the country. That led to the election of the second Constituent Assembly, which has been able to do the task, albeit to heavy criticism.

The long held view that Nepal would prosper once it is federalized has been questioned right from the day the provinces were delineated. This new division of the country is more or less similar to the five development regions that were defined by the Panchyat government for administrative reasons in the early 1970s. An uneven distribution of resources and not addressing the issues of marginalized/ethnic groups may lead to an even more severe conflict in the future, and perhaps clashes between the provinces. Moreover, a provision to centralize revenue collection may deprive the provinces of the means of achieving long-term self-sustainability. The only hope is that the provinces will prosper by collaborating with each other, but that seems unlikely given the ample scope for interest groups to play one off against the other.

The author is a Kathmandu-based consultant & researcher associated with ThinkIN China, Asia. he has co-authored a book, Generation Dialogues: Youth in Politics in Nepal.