A new report from the U.S. Department of Defense, entitled “The Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy,” provides the clearest look to-date at the U.S. military’s view of the maritime situation in the Asia-Pacific region, particularly the maritime disputes in the South China Sea.

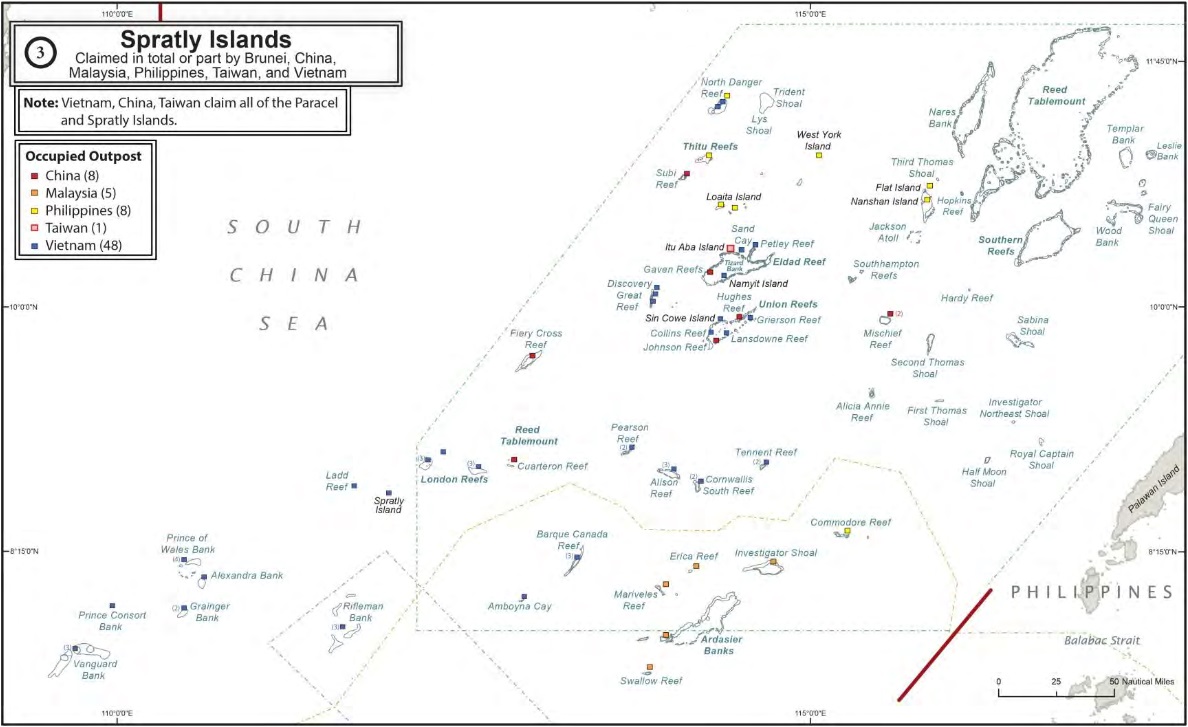

The report includes a detailed section on land reclamation in the South China Sea. While it references earlier efforts by the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Taiwan, the bulk of the analysis focuses on China’s recent activities. The Pentagon reports that from December 2013 to June 2015, China “reclaimed more than 2,900 acres of land… accounting for approximately 95 percent of all reclaimed land in the Spratlys.” That’s up nearly 50 percent over a previous Pentagon estimate in May, which said China has reclaimed about 2,000 acres.

The Wall Street Journal cites a Chinese embassy spokesperson who said that China stopped reclamation in June. Construction on the reclaimed land, however, continues. The Pentagon notes the potential impact once construction is finished:

[China’s] latest land reclamation and construction will also allow it to berth deeper draft ships at outposts; expand its law enforcement and naval presence farther south into the South China Sea; and potentially operate aircraft – possibly as a divert airstrip for carrier-based aircraft – that could enable China to conduct sustained operations with aircraft carriers in the area.

While the report takes a close look at China’s land reclamation activities, Beijing isn’t the only regional government singled out for acting against the spirit of international law. The report notes “excessive maritime claims” on the parts of Malaysia, Vietnam, China, and potentially even Taiwan. While U.S. concerns about risks to freedom of navigation are generally read as criticisms of China’s actions, Malaysia and Vietnam also come under fire in the report: “Malaysia attempts to restrict foreign military activities within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and Vietnam attempts to require notification by foreign warships prior to exercising the right of innocent passage through its territorial sea.”

China, too, would like to restrict or entirely prevent foreign militaries from operating within its EEZ. That, the report warns, could set a dangerous precedent:

Added together, EEZs in the USPACOM [U.S. Pacific Command] region constitute 38 percent of the world’s oceans. If these excessive maritime claims were left unchallenged, they could restrict the ability of the United States and other countries to conduct routine military operations or exercises in more than one-third of the world’ oceans.

China’s attempts to enforce its interpretation of military restrictions within its EEZ have led to what the report calls “unsafe and unprofessional behavior” by Chinese maritime assets in the region, targeting U.S. military aircraft and vessels. However, the report also notes that “since August 2014, U.S.-China military diplomacy has yielded positive results, including a reduction in unsafe intercepts.”

Media reports indicate that the Pentagon would like to see the U.S. take a stronger stance on freedom of navigation – particularly to prove the point that the United States does not recognize any territorial waters around reclaimed features that were previously submerged.

Though China is only one of several South China Sea claimants whose interpretation of freedom of navigation conflicts with the Pentagon’s, it is clear why Washington is most concerned with Beijing. China’s maritime capabilities (and thus its ability to enforce restrictions on maritime activity in regions it claims) far outstrips other claimants. “China is modernizing every aspect of its maritime-related military and law enforcement capabilities, including its naval surface fleet, submarines, aircraft, missiles, radar capabilities, and coast guard,” the report says. “[…]The PLAN now possess the largest number of vessels in Asia, with more than 300 surface ships, submarines, amphibious ships, and patrol craft.”

China’s maritime law enforcement fleet is also “larger than that of all the other claimants combined” and is likely to grow still further, by 25 percent. These “white hulls” are increasingly a key part of the territorial tug-of-war in disputed areas; the report lists the “expanded use of non-military assets to coerce rivals” first in its section on “maritime challenges.”