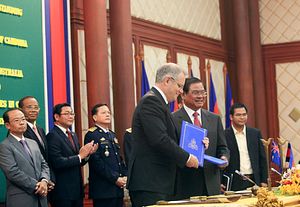

Almost a year after it was signed by both governments, the controversial “refugee deal” between Cambodia and Australia resurfaced in late August when Reuters published an article reporting that Cambodia did not intend to accept any more refugees from Nauru. The article quoted a spokesperson for the Ministry of Interior saying that Cambodia could only accept “a limited amount” of refugees coming from Nauru. In fact, that news should hardly be surprising.

When both governments began to negotiate back in 2014, the Cambodian government was clear: Cambodia could only accept a “limited number of refugees.” According to the agreement signed last September, “[t]he number of Refugees settled, and the timing of their arrival into Cambodia under this MOU, will be subject to the consent of the Kingdom of Cambodia.” And although the Cambodian government backtracked from its first comment, it maintains that the fewer refugees it takes the better.

This, Sophal Ear says, “shows that money talks.” An associate professor of Diplomacy & World Affairs at the Occidental College of Los Angeles and the author of the book Aid Dependence in Cambodia: How Foreign Assistance Undermines Democracy, Ear argues that the 55 million dollars in aid money Cambodia will receive for the next four years in exchange was the only incentive for the Cambodian government to accept such a deal. He adds that bilateral deals “are always about getting something and giving something. […] The only hope here is that it’s public, unlike when China makes a deal. The money is public, but the details are not. […] It seems to me Cambodia has a lot of room, especially if it chooses to say no to anymore refugees and refuses to revise operational guidelines.”

Playing by Its Own Rules?

In Asia, bilateral agreements are accorded much greater significance than they are in many other regions. Dr. Markus Karbaum, an adviser for Southeast Asia at the Heinrich Böll Stiftung, explains that “most governments fear a loss in their national sovereignty when binding to multilateral agreements/organizations.” As such, Cambodia recently broadened its horizons for bilateral agreement as part of its struggle for self-assertion in the region. “Cambodia needs alternatives to its traditional partners China and Vietnam to gain flexibility in its foreign relations,” Karbaum says. To him, the “refugee deal” with Australia is part of this self-assertion strategy.

And since the Paris Peace Agreement in 1991, Cambodia also developed good skills in telling Western donors what they want to hear. Sebastian Strangio, journalist and the author of Hun Sen’s Cambodia, says that “Prime Minister Hun Sen and the Cambodian People’s Party have become experts at mirroring Western narratives of democratic progress and human rights. Too weak to openly resist the demands of foreign donor countries, they have instead simply learned to adapt—by saying all the right things, and then continuing to run the country in much the same way as before.” Based on past precedent, however, he said it would be no surprise if Cambodia walks out of the agreement, or if it comes unstuck in some other way.

Echoing his statement, David Chandler, an American historian and a fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities, notes that “it seems […] that Cambodia has pulled the wool over the Australians’ eyes by letting Australians think that a genuinely beneficial arrangement had been made. The Australians were I suspect hasty, trusting, and naive. […] I am sure [the text] had escape clauses which the Cambodians have now used.” Phil Robertson, the deputy director of the Asia division for the US-based NGO Human Rights Watch, added that “Australia is now getting what it paid for, Cambodia-style – which is to say, not much of anything,” arguing that “there is a huge implementation gap for almost every sort of government project in Cambodia and this refugee deal is no exception,” giving a bitter outcome to this diplomatic precedent.

While Cambodia is no exception to the relative respect of bilateral treaties worldwide, the notion of respect of the rule is another particularity to Cambodian diplomacy. Raoul-Marc Jennar, a Cambodia historian and political scientist explains that the singularity lies in the fact that “the rules governing relationships with other states are the same as the ones governing life in society. As long as there is no precise interest to justify them, there is a general lack of taking the other into account.” He also notes that there is little change from the 1960s diplomacy when the late King Norodom Sihanouk adopted the strategy “to make friends.” To Jennar, it also seems that all the decisions come directly from Phnom Penh, leaving only small room for Cambodian Ambassadors abroad to play a diplomatic role.

Or Solving a Domestic Issue?

Australia signed an agreement it knew could be doomed. Opposition MP Richard Marles called it “an expensive joke” and Senator Hanson-Young also said the government has ignored the signs indicating that the agreement was a sham. To Sophal Ear, Australia is killing the chicken to scare the monkey. This Chinese idiom is used to refer to a tactic that makes an example as out someone or something to warn others. To him, Australia by showing refugees coming by boats what will happen to them, is trying to deter them to reach Australian shores.

But this only has a limited impact, Professor Carlyle Thayer tells The Diplomat. An emeritus professor at the University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy, in Canberra, he states that the Australian strategy is “to tell refugees ‘you will not end up in Australia, but in another country’ to dissuade asylum seekers to come to Australia.” To him, the real political issue is a domestic problem. “Australia should still be able to control who is coming to the country. However, instead of putting more financial efforts into determining whether asylum seekers have a well-founded fear not to return home, Australia is actually evading the UN Convention.” And to Thayer, Cambodia is welcoming too few refugees for Australia to manage to dissuade asylum seekers.

Therefore, the recent Cambodian disruption of the Australian government strategy is rather a symbolic setback than a political one. Thayer also says he would have trouble understanding why Cambodia would accept asylum seekers. “Usually, they go for the money. What can you offer to a corrupt regime? But, this is also a delicate situation for Cambodia. If they accept asylum seekers from Nauru, why don’t they accept Montagnards or Uighurs? I do not believe that the Cambodia government has any genuine interest in accepting asylum seekers.”

And on September 11, almost a year after a few hundred Montagnards fled Vietnam to request asylum in Cambodia, the ministry of Interior stated that they would all be repatriated to Vietnam. There are now 200 awaiting their asylum application in Phnom Penh.

To Dr. Karbaum, Cambodia is now stuck in difficult situation for its image. “If the Cambodian government terminates the agreement without refunding Australia’s pledges, it runs the risk to ruin its reputation a bit more. I am sure that Prime Minister Hun Sen is fully aware of this obvious consequence and will undertake everything to avoid being perceived as an unreliable partner by other leaders.”

Clothilde Le Coz is an independent journalist based in Cambodia and covering social and technology topics.